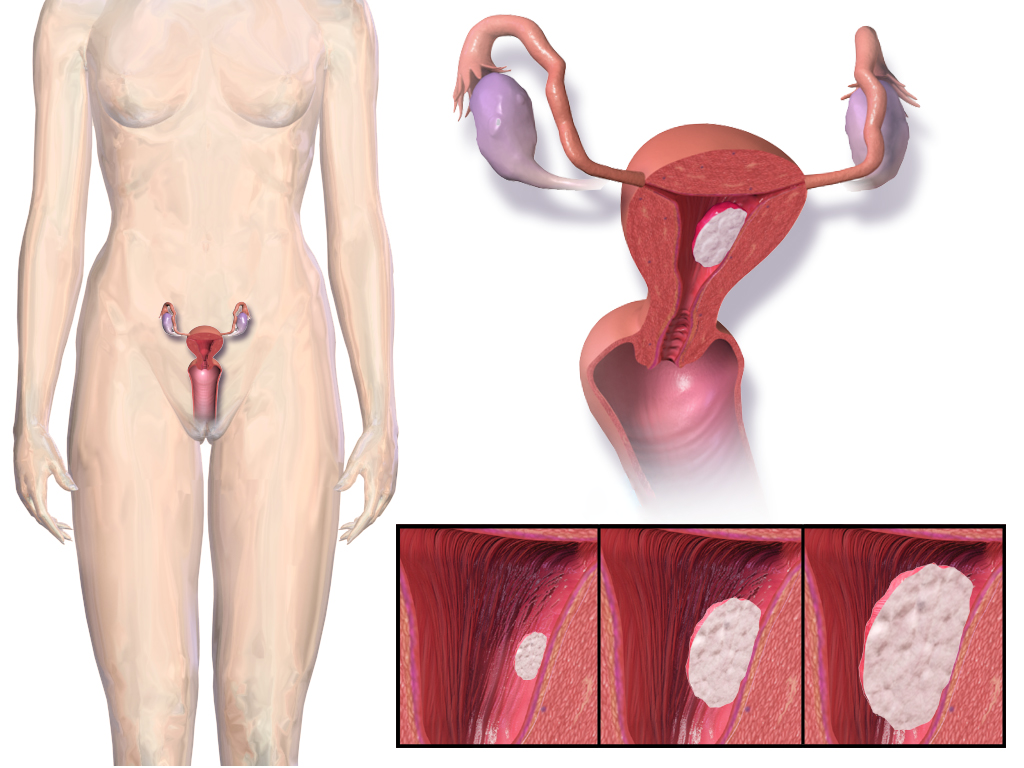

Endometrial cancer develops in uterine lining and is typically accompanied by heavy menstrual bleeding. Illustration by Blausen Medical Communications, Inc. via Wikipedia CC license.

By Barbara Clements, UW Communications

Most women now know to how to check for breast cancer. And a yearly pap smear to check for cervical cancer is de rigueur. But awareness of endometrial cancer, not so much.

That bothers Dr. Kemi Doll, a gynecologic oncologist with the University of Washington School of Medicine.

“The truth is, this is the most common gynecological cancer in the U.S.,” said Doll. “It’s four times more common than cervical cancer. It’s twice as common as ovarian cancer.”

If endometrial cancer is caught early, it is almost always curable, Doll said. The cancer affects the uterine lining and is typically accompanied by heavy menstrual bleeding.

The median age for being diagnosed is 62, so a woman’s risk is generally greater during or after menopause. But doctors are seeing the condition more in younger women, as well.

Another troubling reality with this disease is the strong racial disparity in survival of African-American women compared with Caucasian women. In the United States, black women have a 90 percent higher mortality rate than all other groups of women with this cancer, she said.

“This is actually a larger difference in terms of a racial disparity than we see in breast cancer and colon cancer, so I really wanted there to be a visible community of black women who have been diagnosed with this disease to show they can survive and thrive,” Doll said. That’s why, in 2017, she founded ECANA, or the Endometrial Cancer Action Network for African-Americans. She helped organize the first national conference on this topic, in March.

There are multiple reasons black women die more often from this cancer, as well as other health problems, Doll said.

“Part of it is that they simply don’t know about this condition, so they might have been bleeding for months or years before being evaluated.” As well, “the quality of our healthcare system really isn’t the same for black women as it is for everyone else, especially when it comes to their reproductive healthcare,” Doll said.

African-American women also seem more prone to contract more aggressive types of endometrial cancer than other demographic groups. No one knows why this is the case; Doll is researching possible causes.

Such health inequities don’t exist in a vacuum, Doll knows.

“We need more women doctors who look like the women that we serve. We need more research that’s really grounded in what the community needs. And we need to decide as a medical community that’s it’s simply unacceptable that a black women would suffer more from conditions than other women in this country,” she said.