By Christine Vestal, Stateline

Margery Smelkinson, a mother with four kids in an elementary school in Montgomery County, Maryland, suspects that the parent group she joined had something to do with Republican Gov. Larry Hogan’s recent announcement that all schools must reopen by March 1.

“Out of desperation,” she said, representatives of her group and others in the state met with Hogan days before his Jan. 21 announcement and asked him to intervene in deadlocked local negotiations over when and how to open schools.

“While millions of students across the country have safely returned to classrooms, Maryland has remained one of only six states with little to no in-person instruction,” her coalition of more than 15,000 residents wrote. “We have watched as our kids have suffered severe academic loss, declining grades, social isolation and an increase in mental illness.”

Maryland law doesn’t allow the state to force school districts to open, but the governor can apply fiscal pressure to do so. So far, it’s not clear whether Montgomery County schools will meet the governor’s deadline, Smelkinson said.

Maryland is one of six states—alongside California, New Mexico, Oregon, Virginia and Washington—where most school districts have remained closed for in-person instruction since the pandemic began, said Dennis Roche, co-founder of New York-based school data group Burbio.

“The question now is whether those governors can rally support for reopening schools and persuade teachers to return to classrooms after standing on the sidelines for so long,” he said.

Similarly, liberal mayors in Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Los Angeles, Philadelphia and San Francisco are facing stiff opposition from local teachers’ unions as they try to reopen schools. Many teachers, the unions report, are concerned about their own safety and would like to be vaccinated before they return to in-person teaching. Some states bumped teachers up in the vaccine line in response.

In some places, unions also are calling for improvements to ventilation systems in schools and other changes to buildings to lower the virus transmission risk. In Washington, D.C., and Chicago, they have threatened strikes if they are forced to resume in-person instruction without their concerns being addressed.

Meanwhile, the Biden administration has said it wants schools to reopen as quickly as possible. And last week, three scientists from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention authored an article in JAMA, the journal of the American Medical Association, that concluded there is “little evidence that schools have contributed meaningfully to increased community transmission.”

In Maryland and other states and cities where most students haven’t stepped foot in a classroom since the pandemic began, the battles are pitched. Many local districts are setting February and March deadlines for opening schools. But it’s unclear whether those targets will be met.

“There’s been a lot of confusion and a lot of backlash and hate,” Smelkinson said. “I’ve been called a racist,” she said, explaining that minority families in the county are generally opposed to returning to classrooms out of fear for their children’s health. “We’re simply asking for the choice to send our kids back to school. Families who don’t want to come can wait until they feel safe,” she said.

National political rhetoric over school closings has toned down since the Trump administration ended, said Jon Valant, an education expert at the Brookings Institution, a nonpartisan think tank based in Washington, D.C.

But there are variables other than partisanship that are complicating local decisions, he said, including the potentially more infectious coronavirus variants, the chaotic rollout of vaccines and recently reported spates of suicides by teens despondent over being cut off from friends and school activities.

As states and cities move teachers to the tops of priority lists for vaccines, parents and elected officials are increasingly pushing unions and local administrators to open schools. As of now, though, it’s anyone’s guess whether states and cities will meet their latest deadlines, Valant said.

Holdouts

Roche, who has been collecting data on school openings from 1,200 of the nation’s school districts since the pandemic began, is doubtful the move to in-person learning will go smoothly.

On his first day in office, President Joe Biden outlined a plan for getting the nation’s more than 50 million public school students back into classrooms within his first 100 days. A few days later, the CDC noted that COVID-19 didn’t spread as rapidly in schools as it did in local communities.STATELINE STORY November 13, 2020The Pendulum Was Swinging Toward Reopening Schools. Then Came the Surge.

In response, education experts and national teacher unions predicted it was only a matter of time before in-person learning would resume for most American students.

Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, the second largest teachers union in the country, wrote in an op-ed that “even before the new vaccines are widely available—the nation’s more than 98,000 public schools could be open soon, getting students back to in-person learning.”

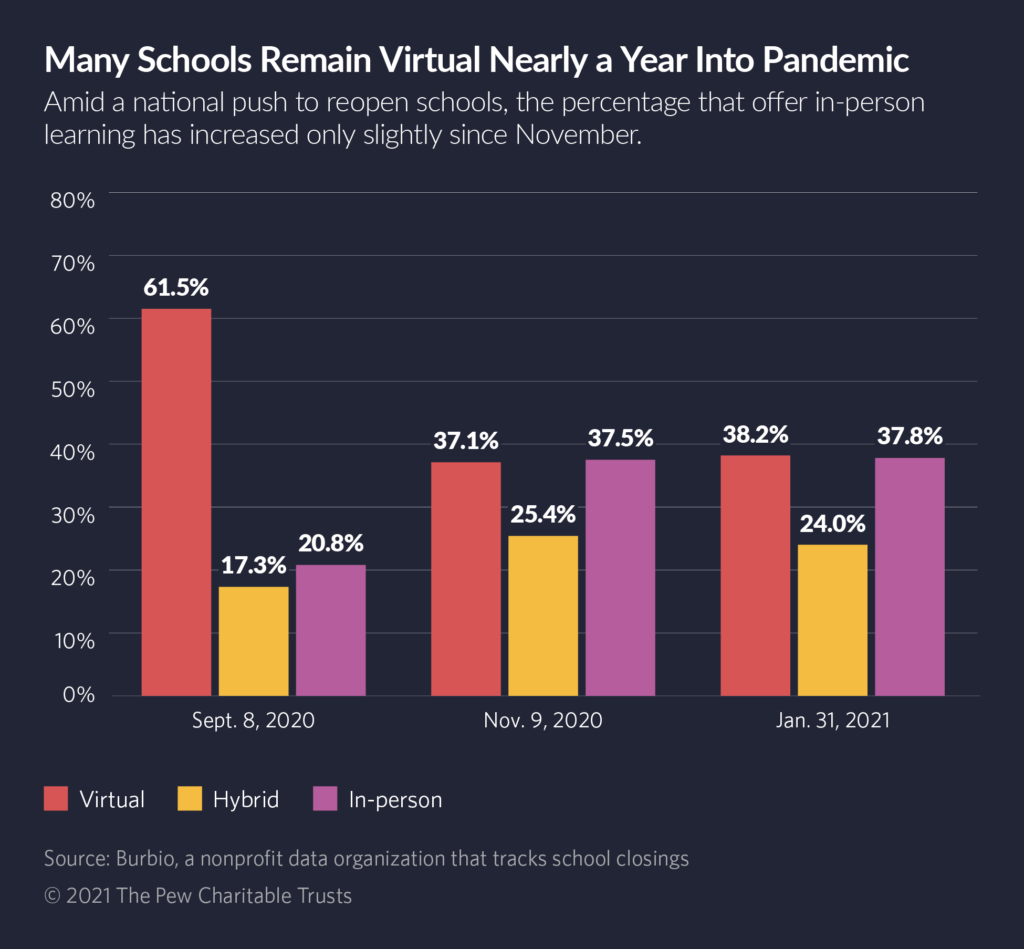

But as of Jan. 31, only 38% of U.S. K-12 students were attending classes in person, five days a week, according to Burbio data, which is updated weekly.

That’s only a slight increase in the number of students in classrooms since November, when scientific evidence began emerging about the success of mask wearing, social distancing, testing and ventilation strategies in schools.

At the beginning of the school year, only 21% of students were learning in person, 62% were learning online and 17% were attending in-person classes two days a week under a hybrid model, according to Burbio. The numbers are shifting toward more in-person learning, but not quickly.

“I’m afraid that governors and mayors may have lost their window of opportunity to compel teachers to return to schools,” said Marguerite Roza, a research professor and expert on education finance and policy at Georgetown University.

“If they didn’t push to open schools early in the pandemic, they’re now finding that teachers who have been working from the safety of their homes are afraid to go back into school buildings. Over the 10 months since the pandemic began, their fear has grown and taken root.”STATELINE STORY July 29, 2020Virtual Learning Means Unequal Learning

In Maryland, Hogan pointed to growing scientific evidence that there is no public health reason to keep students out of schools. Smelkinson, an infectious disease scientist, asked “If science isn’t going to determine when we open schools. What is?”

According to Roza, “It doesn’t matter at this point what the public health data says or how much funding the governor is providing to make schools safe. Fear is fear.”

Shifting Attitudes

In the early days of the pandemic, Republican governors in the South, Midwest and West urged districts to reopen schools. Before the new school year started, governors in three states—Florida, Iowa and Texas—demanded that schools resume in-person learning.

At the same time, most Democratic governors left school closure decisions up to local jurisdictions and public health officials.

In blue states, governors generally agreed that once COVID-19 infection rates dipped below certain thresholds set by public health officials, schools could reopen.

As the virus spread, low infection-rate thresholds were never met in many places. Meanwhile governors mostly stuck to their original plans, leaving local school boards to placate parents who were becoming increasingly frustrated as their kids struggled to learn online.

“It doesn’t matter at this point what the public health data says or how much funding the governor is providing to make schools safe. Fear is fear.”

Marguerite Roza, education policy professor at Georgetown University

By June, then-President Donald Trump declared that all schools must reopen and told the CDC to adjust its infection rate guidelines accordingly.

That cemented many Democratic governors’ resolve to go in the opposite direction, hardening their positions on not opening schools until infection levels fell to safer levels.

By July and August, research showed that national politics had more to do with school opening decisions than the level of coronavirus infection in states and local school districts.

“It seemed that school districts, which are historically nonpartisan, got wrapped up in the larger national debate about how we should respond to COVID,” said Michael Hartney, an assistant professor of political science at Boston College and co-author of a recent study tying national politics to school closure decisions.STATELINE STORY December 21, 2020Quarantines Leave Schools Scrambling for Substitute Teachers

Another study, conducted by researchers at the Brookings Institution, came to the same conclusion.

By November, attitudes were shifting in favor of opening schools, but in the weeks before the holidays, the virus began spiking almost everywhere, curtailing what had been a gradual shift toward more in-person learning.

Meanwhile, many of the governors who have largely left reopening decisions to local districts are discovering they don’t have as much leverage as they thought they did, Roza said.

Deeply Divided

Ashley Jochim, a researcher at Seattle-based nonprofit policy group The Center on Reinventing Public Education, said deep divides at the local level have hardened.

“There’s little question that superintendents and school boards are hemmed in by local politics. Whatever their ambitions may be about reopening school, ultimately they are responsible to stakeholders.”

Attitudes about reopening schools in any given community vary widely.

Parents who are essential workers and can’t afford child care often want schools to open as soon as possible. Wealthier parents who have hired tutors or sent their kids to private schools often show less urgency. And families of color, which studies show are suffering the most from school closings, tend to oppose sending kids back into classrooms, because they’ve seen many of their friends and family members die of COVID-19.

Teacher attitudes also vary. Many are fearful of becoming infected, while others are convinced by new public health studies. Some long for the energy they get from classroom teaching and others say they get enough feedback from students online.

Teachers generally agree that students are suffering and need to return to classrooms, but the uncertainty over the last year about when and how schools would reopen has left them and parents in limbo.

Mary Lynn Rynkiewicz, a high school English teacher in Fairfax County, Virginia, said the school board has repeatedly missed proposed start dates, causing her to lose sleep. Her husband is an engineer who works from home. What if she brings the virus home and infects him? “You mentally prepare for how the change will affect your life and then it doesn’t happen,” she said.

Rynkiewicz has been teaching online-only this school year and has never met her students. She says she’s looking forward to going into the classroom, possibly later this month. “With high school students, online teaching is like talking into a void.” They’re not required to turn on their cameras or talk and most don’t, she said.

An elementary school teacher in Montgomery County who requested anonymity had the opposite view. He said he would prefer to keep teaching his kindergarten students from home. “They don’t have any problem talking to me through their tablets,” he said. Plus, he has two young children of his own to look after, since his wife is an essential health care worker.

As a parent, he said, “I wouldn’t choose to send my kids to school to sit at a desk with tape around it and social distance in the hallway. To me that’s worse than what we have at home.”

But he said he’ll go back into the classroom if the district tells him to. “It’s the not knowing that adds layers of stress upon layers of stress.”

At the national level, Jochim said, “there was an opportunity to be decisive and produce clear and definitive guidelines around school reopening. But a year into the pandemic, it’s too late for that.

“Now the biggest roadblock to schools reopening is skepticism and fear among teachers and families,” she said. “A path forward will require deeper communication to engage families and teachers about COVID safety to make people feel more comfortable about returning to schools. That’s not likely to happen overnight.”