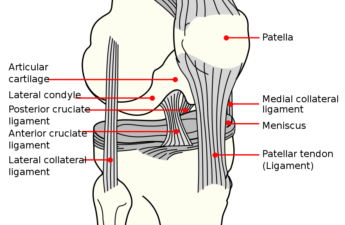

Knee surgery is common. Young adults have their anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed after tearing it when playing sports. Middle-aged people have parts of their meniscus trimmed when they have pain and limited knee mobility.

And older people have their knees replaced by metal and plastic when their cartilage has worn out. The idea that there is something mechanically wrong that needs to be fixed with orthopaedic surgery is a compelling idea – but is it right?

Total joint replacement is the greatest orthopaedic innovation and has doubtless improved the lives of millions of people around the world. The rate of total knee replacement increased fourfold in Denmark over ten years, and is expected to continue to rise as the population gets older, more overweight and more physically inactive.

In the UK, by 2035, it is projected that 118,666 knee replacements will be performed. However, replacing the knee joint with metal and plastic is not associated with pain relief for everyone.

About two out of ten people who undergo the procedure do not experience any pain relief at all and may actually be worse off after surgery than before.

Older people

In older people, only one study has randomly allocated patients to test whether total knee replacement plus an extensive non-surgical treatment package gave more pain relief and functional improvement compared with getting just the non-surgical treatment package, where the non-surgical package included patient education, supervised exercise therapy, seeing a dietitian if overweight, using biomechanical insoles in shoes and taking painkillers, if needed.

In this study, which I was involved with, we found that the combination of surgery and the treatment package was associated with twice the improvement in pain and function compared with having the treatment package only.

However, surgery came with a price. About one in ten people had a serious adverse event, such as a blood clot or an infection, requiring more treatments in hospital, including more surgery. While most of these people recovered fully, a few experienced long-term debilitating consequences.

In the non-surgical group, we found that most people did not opt to have the surgery during the first two years. Having the non-surgical treatment package only was associated with 30% pain relief, which was enough for three out of four participants to postpone surgery for at least one year. At two years, two out of three had still not had the surgery.

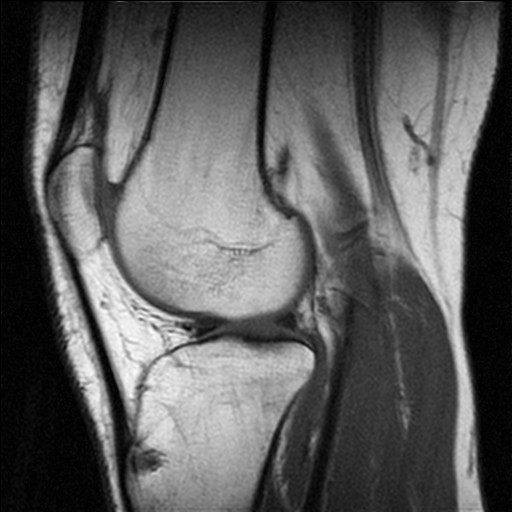

All the people in the study had moderate to severe loss of cartilage – in other words: bone-on-bone osteoarthritis – and most were overweight or obese. All had been told by an orthopaedic surgeon that they fulfilled the requirements to have the surgery and were told they could have the surgery whenever they wanted.

Middle-aged people

In middle-age people, there have been more than ten high-quality studies of treating knee pain, osteoarthritis and meniscal tears with knee arthroscopy. Two of these studies compared real surgery with sham surgery, where either only skin incisions were made, or the mechanical problem thought to cause the pain and problems was never treated (it was only saline that was washed through the joint). In both studies, there was no difference in outcomes between the people who had real surgery versus those who had sham surgery.

Another study, which we conducted, compared real surgery with exercise therapy and similarly found that both groups improved with no difference between groups in pain relief. However, the exercise group improved their muscle strength – which is not surprising – and kept that improvement for one year – which is surprising since the exercise intervention only lasted 12 weeks.

The group who had surgery actually got weaker from the surgery and it took them a year to regain the strength they had before the surgery. We also found that the group having just exercise therapy was more physically active two years after the study.

Young people

In young adults tearing their anterior cruciate ligament in sports, only one study has compared extensive exercise therapy only with extensive exercise therapy combined with reconstructing the anterior cruciate ligament. In that study, we found no difference between the treatment groups in any measured outcome at two or five years.

Both groups improved and there was no difference in improvement between the group that had surgery and the group that didn’t. Every other person in the exercise only group had their knee ligament reconstructed later, but that did not result in a better outcome compared with those staying with exercise only.

A common reason to have the surgery later was the belief that surgery is needed to fix the problem, and the desire to return to sport. Unfortunately, only four out of ten returned to sport in our study, with no difference between those having had the surgery or not.

When summarising return to sport rates across all studies available for young people who have had surgical reconstruction following a tear of the anterior cruciate ligament, only about one in two athletes are able to return to sport.

Not necessarily so

It is intuitive to think that when something is broken in the knee, fixing it with surgery is necessary. Research shows this is not necessarily so. Surgery is not the only solution. Research shows that several types of knee problems can resolve to a similar extent without surgery, but surgery or not, an excellent outcome cannot be guaranteed.

It seems smart to learn more about the injury or disease and the available treatment options, get to know how you can tackle it yourself and invest your time in a couple of months of supervised exercise therapy. This way you can maybe avoid or delay surgery – and, if you are going to have the surgery anyhow, you will recover faster, be stronger and feel better if you exercised before the surgery.

![]() Surgery or not, a factor determining the outcome is good muscle strength and good muscle function. And, importantly, exercise and being more physically active will help improve your general health; it is not only beneficial for the knee.

Surgery or not, a factor determining the outcome is good muscle strength and good muscle function. And, importantly, exercise and being more physically active will help improve your general health; it is not only beneficial for the knee.

Ewa M Roos, Professor of Muscle and Joint Health, University of Southern Denmark

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.