Stateline

Toward the end, the pain had practically driven Elizabeth Martin mad.

By then, the cancer had spread everywhere, from her colon to her spine, her liver, her adrenal glands and one of her lungs. Eventually, it penetrated her brain. No medication made the pain bearable. A woman who had been generous and good-humored turned into someone hardly recognizable to her loving family: paranoid, snarling, violent.

Sometimes, she would flee into the California night in her bedclothes, “as if she were trying to outrun the pain,” her older sister Anita Freeman recalled.

Martin fantasized about having her sister drive her into the mountains and leave her with the liquid morphine drops she had surreptitiously collected over three months — medicine that didn’t relieve her pain but might be enough to kill her if she took it all at once. Freeman couldn’t bring herself to do it, fearing the legal consequences and the possibility that her sister would survive and end up in even worse shape.

California’s aid-in-dying law, authorizing doctors to prescribe lethal drugs to certain terminally ill patients, was still two years from going into effect in 2016. But Martin did have one alternative to the agonizing death she feared: palliative sedation.

Under palliative sedation, a doctor gives a terminally ill patient enough sedatives to induce unconsciousness. The goal is to reduce or eliminate suffering, but in many cases the patient dies without regaining consciousness.

The medical staff at the Long Beach acute care center where Martin was a patient gave her phenobarbital. Once they calibrated the dosage properly, she never woke up again. She died within a week, not the one or two months her doctors had predicted before the sedation. She was 66.

“At least she got into that coma state versus four to eight weeks of torture,” Freeman said.

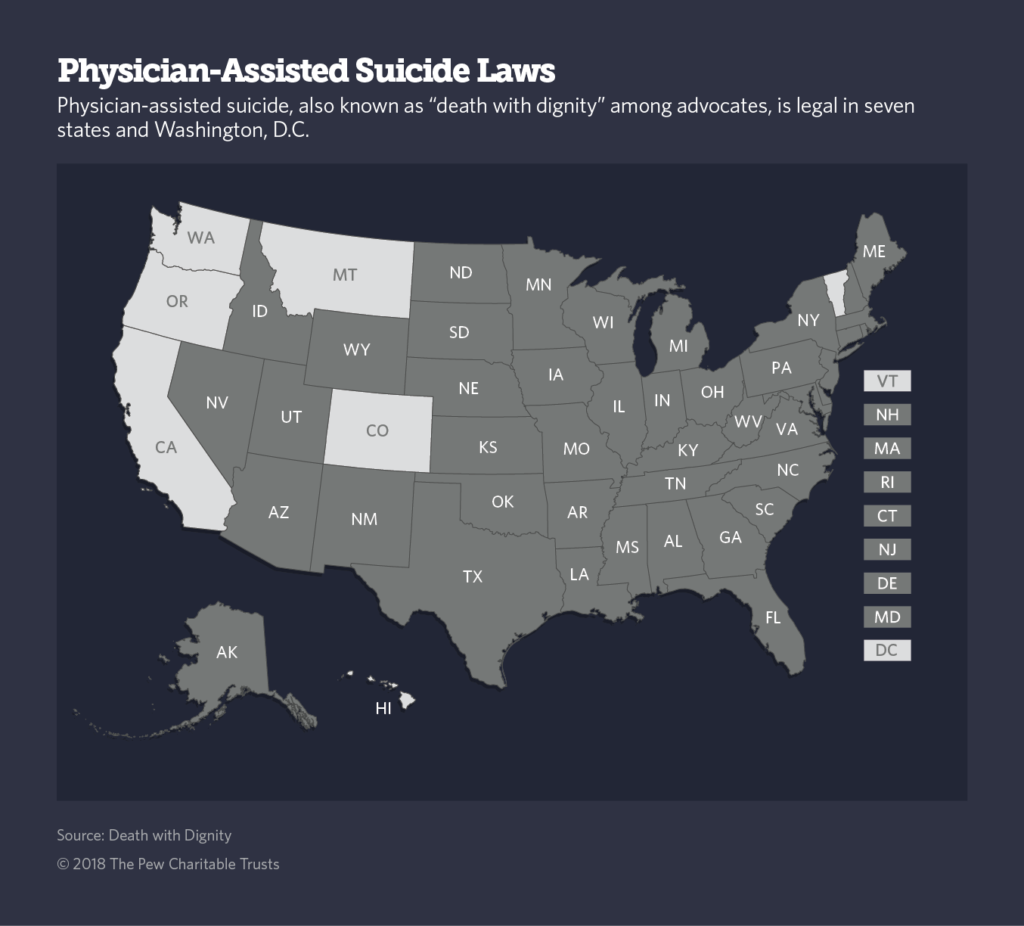

While aid-in-dying, or “death with dignity,” is now legal in seven states and Washington, D.C., medically assisted suicide retains tough opposition. Palliative sedation, though, has been administered since the hospice care movement began in the 1960s and is legal everywhere.

Doctors in Catholic hospitals practice palliative sedation even though the Catholic Church opposes aid-in-dying. According to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, the church believes that “patients should be kept as free of pain as possible so that they may die comfortably and with dignity.”

Since there are no laws barring palliative sedation, the dilemma facing doctors who use it is moral rather than legal, said Timothy Quill, who teaches psychiatry, bioethics and palliative care medicine at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York.

Some doctors are hesitant about using it “because it brings them right up to the edge of euthanasia,” Quill said.

But Quill believes that any doctor who treats terminally ill patients has an obligation to consider palliative sedation. “If you are going to practice palliative care, you have to practice some sedation because of the overwhelming physical suffering of some patients under your charge.”

Doctors wrestle with what constitutes unbearable suffering, and at what point palliative sedation is appropriate — if ever. Policies vary from one hospital to another, one hospice to another, and one palliative care practice to another.

Not Euthanasia

The boundary between aid-in-dying and palliative sedation “is fuzzy, gray and conflated,” said David Grube, a national medical director at the advocacy group Compassion and Choices. In both cases, the goal is to relieve suffering.

But many doctors who use palliative sedation say the bright line that distinguishes palliative sedation from euthanasia, including aid-in-dying, is intent.

“There are people who believe they are the same. I am not one of them,” said Thomas Strouse, a psychiatrist and specialist in palliative care medicine at the UCLA Medical Center. “The goal of aid-in-dying is to be dead; that is the patient’s goal. The goal in palliative sedation is to manage intractable symptoms, maybe through reduction of consciousness or complete unconsciousness.”

Other groups such as the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, which advocates for quality end-of-life care, recommend that providers use as little medication as needed to achieve “the minimum level of consciousness reduction necessary” to make symptoms tolerable.

Sometimes that means a light unconsciousness, in which the patient may still be somewhat aware of the presence of others. On other occasions it might mean a deep unconsciousness, not unlike a coma. In some cases, the palliative sedation is limited; in others it continues until death.

Whether palliative sedation hastens death remains an open question. Pain-management doctors say sedation slows breathing and lowers blood pressure and heart rates to potentially dangerous levels.

In the vast majority of cases, it is accompanied by the cessation of food, drink and antibiotics, which can precipitate death. But palliative sedation is also administered when the underlying disease has made death imminent.

“Some patients are super sick,” Quill said. “The wheels are coming off, they’re delirious, out of their minds.”

In that circumstance, palliative sedation doesn’t accelerate death, he said. “For other patients who are not actively dying, it might hasten death to some extent, bringing it on in hours rather than days.” He emphasized, however, that in all cases the goal isn’t death but relief from suffering.

One review of studies on palliative sedation concluded that it “does not seem to have any detrimental effect on survival of patients with terminal cancer.” But even that 30-year survey acknowledged that, without randomized control trials, it’s impossible to be definitive.

‘Existential Suffering’

There is widespread agreement that palliative sedation is appropriate for intractable physical pain, extreme nausea and vomiting when other treatments have failed.

Doctors are divided about whether palliative sedation is appropriate for alleviating suffering that is not physiological, what medical journals refer to as “existential suffering.” The hospice and palliative care group defines it as “suffering that arises from a loss or interruption of meaning, purpose, or hope in life.”

Some argue that such suffering is every bit as agonizing as physical suffering. Existential suffering is the motivation that prompts many to seek aid-in-dying.

Terminally ill patients who took their own lives under Oregon’s aid-in-dying law were far less likely to cite physical pain than psychosocial reasons such as loss of autonomy, loss of dignity or being a burden on loved ones.

Using palliative sedation to relieve existential suffering is less common in the United States than it is in other Western countries, according to UCLA’s Strouse and other American practitioners. “I am not comfortable with supplying palliative sedation for existential suffering,” Strouse said. “I’ve never done that and probably wouldn’t.”

In states where aid-in-dying is legal, terminally ill patients rarely choose between aid-in-dying and palliative sedation, said Anthony Back, co-director of the University of Washington’s Cambia Palliative Care Center of Excellence. In Washington, patients with a prognosis of six months to live or less must make two verbal requests to their doctor at least 15 days apart and sign a written form. They also must be healthy enough to take the legal drugs themselves.

“If you are starting the death-with-dignity process, you’re not at a point where a doctor would recommend palliative sedation,” Back said. “And with terminal sedation, the patient doesn’t have that kind of time and is too sick to take all those meds orally,” he said of the aid-in-dying drugs.

But Back does tell terminally ill patients who don’t want or don’t qualify for aid-in-dying that, when the time is right and no other treatments alleviate their symptoms, “I would be willing to make sure that you get enough sedation so you won’t be awake and miserable.”

Whether palliative sedation truly ends suffering is not knowable, although doctors perceive indications that it does.

“You might be able to tell if their blood pressure goes up. Same with their pulse,” said Nancy Crumpacker, a retired oncologist in Oregon. “And you read their faces. If they are still bothered somehow, it will show in their facial expression.”

[Photo: Harlan Seymour]

Harlan Seymour didn’t need to rely on those signs after his wife, Jennifer Glass, a well-known San Francisco public relations executive, received palliative sedation in 2015. A nonsmoker, she had metastatic lung cancer and faced a miserable death from suffocation brought on by fluids filling her lungs, her husband said.

She desperately wanted to die, he said, but aid-in-dying, which she advocated for, wasn’t yet legal. Instead, she received palliative sedation.

“The expectation was this cocktail would put her into a peaceful sleep and she would pass away” within a day or two, Seymour said. “Instead, she woke up the third night in a panic.”

Doctors upped her dosage, putting her into a deep unconsciousness. Still, she didn’t die until the seventh day. She was 52. Seymour wishes aid-in-dying had been available for his wife, but he did regard palliative sedation as a mercy for her.

“Palliative sedation is slow-motion aid-in-dying,” he said. “It was better than being awake and suffocating, but it wasn’t a good alternative.”