From the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Public Health Matters Blog

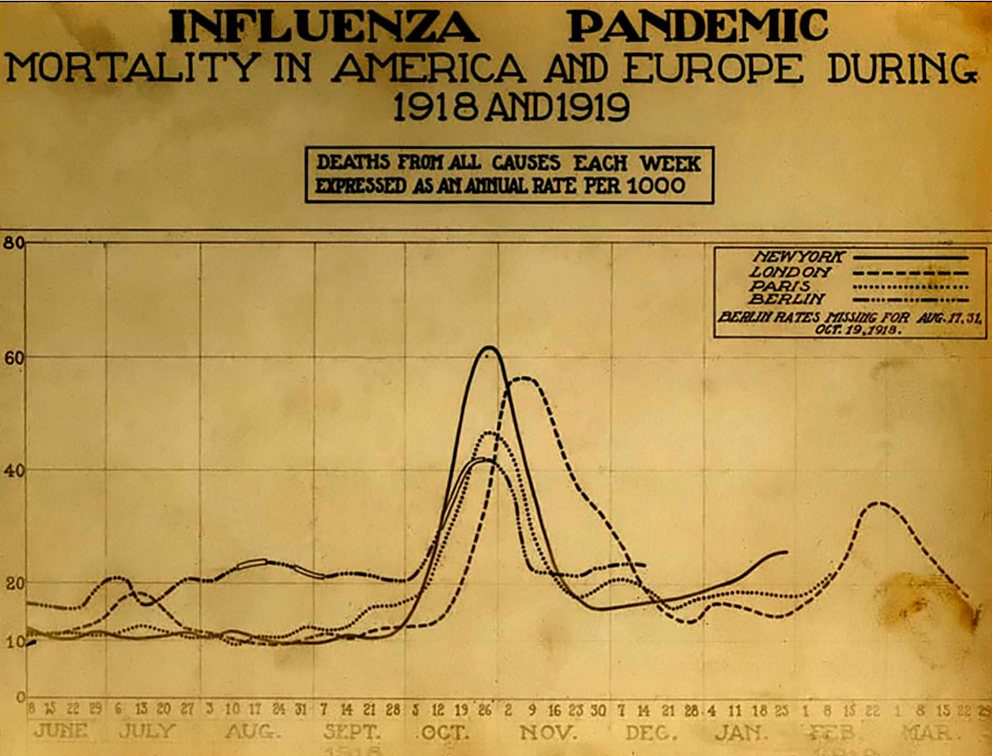

100 years ago, an influenza (flu) pandemic swept the globe, infecting an estimated one-third of the world’s population and killing at least 50 million people. The pandemic’s death toll was greater than the total number of military and civilian deaths from World War I, which was happening simultaneously.

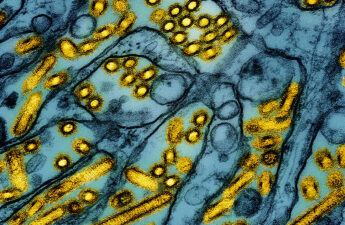

At the time, scientists had not yet discovered flu viruses, but we know today that the 1918 pandemic was caused by an influenza A (H1N1) virus. The pandemic is commonly believed to have occurred in three waves. Unusual flu-like activity was first identified in U.S. military personnel during the spring of 1918. Flu spread rapidly in military barracks where men shared close quarters. The second wave occurred during the fall of 1918 and was the most severe. A third wave of illness occurred during the winter and spring of 1919.

Here are 5 things you should know about the 1918 pandemic and why it matters 100 years later.

1. The 1918 Flu Virus Spread Quickly

500 million people were estimated to have been infected by the 1918 H1N1 flu virus. At least 50 million people were killed around the world including an estimated 675,000 Americans. In fact, the 1918 pandemic actually caused the average life expectancy in the United States to drop by about 12 years for both men and women.

In 1918, many people got very sick, very quickly. In March of that year, outbreaks of flu-like illness were first detected in the United States. More than 100 soldiers at Camp Funston in Fort Riley Kansas became ill with flu. Within a week, the number of flu cases quintupled.

There were reports of some people dying within 24 hours or less. 1918 flu illness often progressed to organ failure and pneumonia, with pneumonia the cause of death for most of those who died. Young adults were hit hard. The average age of those who died during the pandemic was 28 years old.

2. No Prevention and No Treatment for the 1918 Pandemic Virus

In 1918, as scientists had not yet discovered flu viruses, there were no laboratory tests to detect, or characterize these viruses. There were no vaccines to help prevent flu infection, no antiviral drugs to treat flu illness, and no antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections that can be associated with flu infections. Available tools to control the spread of flu were largely limited to non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI’s) such as isolation, quarantine, good personal hygiene, use of disinfectants, and limits on public gatherings, which were used in many cities.

The science behind these was very young, and applied inconsistently. City residents were advised to avoid crowds, and instructed to pay particular attention to personal hygiene. In some cities, dance halls were closed. Some streetcar conductors were ordered to keep the windows of their cars open in all but rainy weather. Some municipalities moved court cases outside. Many physicians and nurses were instructed to wear gauze masks when with flu patients.

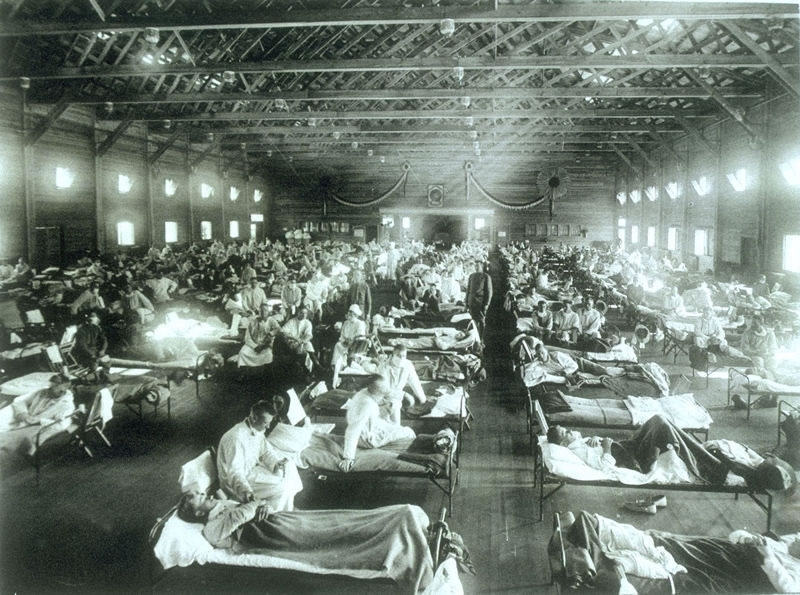

3. Illness Overburdened the Health Care System

An estimated 195,000 Americans died during October alone. In the fall of 1918, the United States experienced a severe shortage of professional nurses during the flu pandemic because large numbers of them were deployed to military camps in the United States and abroad. This shortage was made worse by the failure to use trained African American nurses. The Chicago chapter of the American Red Cross issued an urgent call for volunteers to help nurse the ill. Philadelphia was hit hard by the pandemic with more than 500 corpses awaiting burial, some for more than a week.

Many parts of the U.S. had been drained of physicians and nurses due to calls for military service, so there was a shortage of medical personnel to meet the civilian demand for health care during the 1918 flu pandemic. In Massachusetts, for example, Governor McCall asked every able-bodied person across the state with medical training to offer their aid in fighting the outbreak.

As the numbers of sick rose, the Red Cross put out desperate calls for trained nurses as well as untrained volunteers to help at emergency centers. In October of 1918, Congress approved a $1 million budget for the U. S. Public Health Service to recruit 1,000 medical doctors and more than 700 registered nurses.

At one point in Chicago, physicians were reporting a staggering number of new cases, reaching as high as 1,200 people each day. This in turn intensified the shortage of doctors and nurses. Additionally, hospitals in some areas were so overloaded with flu patients that schools, private homes and other buildings had to be converted into makeshift hospitals, some of which were staffed by medical students.

4. Major Advancements in Flu Prevention and Treatment since 1918

The science of influenza has come a long way in 100 years! Developments since the 1918 pandemic include vaccines to help prevent flu, antiviral drugs to treat flu illness, antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections such as pneumonia, and a global influenza surveillance system with 114 World Health Organization member states that constantly monitors flu activity. There also is a much better understanding of non-pharmaceutical interventions–such as social distancing, respiratory and cough etiquette and hand hygiene–and how these measures help slow the spread of flu.

There is still much work to do to improve U.S. and global readiness for the next flu pandemic. More effective vaccines and antiviral drugs are needed in addition to better surveillance of influenza viruses in birds and pigs. CDC also is working to minimize the impact of future flu pandemics by supporting research that can enhance the use of community mitigation measures (i.e., temporarily closing schools, modifying, postponing, or canceling large public events, and creating physical distance between people in settings where they commonly come in contact with one another). These non-pharmaceutical interventions continue to be an integral component of efforts to control the spread of flu, and in the absence of flu vaccine, would be the first line of defense in a pandemic.

5. Risk of a Flu Pandemic is Ever-Present, but CDC is on the Frontlines Preparing to Protect Americans

Four pandemics have occurred in the past century: 1918, 1957, 1968, and 2009. The 1918 pandemic was the worst of them. But the threat of a future flu pandemic remains. A pandemic flu virus could emerge anywhere and spread globally.

CDC works to protect Americans and the global community from the threat of a future flu pandemic. CDC works with domestic and global public health and animal health partners to monitor human and animal influenza viruses. This helps CDC know what viruses are spreading, where they are spreading, and what kind of illnesses they are causing. CDC also develops and distributes tests and materials to support influenza testing at state, local, territorial, and international laboratories so they can detect and characterize influenza viruses.

In addition, CDC assists global and domestic experts in selecting candidate viruses to include in each year’s seasonal flu vaccine and guides prioritization of pandemic vaccine development. CDC routinely develops vaccine viruses used by manufacturers to make flu vaccines. CDC also supports state and local governments in preparing for the next flu pandemic, including planning and leading pandemic exercises across all levels of government. An effective response will diminish the potential for a repeat of the widespread devastation of the 1918 pandemic.

Visit CDC’s 1918 commemoration website for more information on the 1918 pandemic and CDC’s pandemic flu preparedness work.