Just How Profitable Should Your Disease Be?

By: Elaine S. Povich

Stateline

VAN NUYS, Calif. — Audrey Thomas, a 39-year-old dialysis patient who also is a dialysis technician, smiles as she describes her clinic in this Southern California city as nothing short of a blessing: Clean, efficient and welcoming, it provides her with a decent salary and a flexible schedule so she can get her treatments, work and go to school at the same time.

A few miles away, dialysis patient Tangi Foster and dialysis worker Emanuel Gonzales have decidedly different views.

Foster, an animated 60-year-old, says her technicians are overworked and pressed to shorten turnaround times for patients. She recalls a time after her dialysis when a cockroach came home in her bag. Gonzales, 25, who saw his father endure kidney disease long before he got into the profession, says workers often pick up extra shifts to make up for the low pay, meaning they can work six days a week when clinics are short-staffed.

Even then, he said, there are sometimes not enough workers on a floor. He recalls a Halloween two years ago when a patient had a heart attack, and since all of the available staffers were working to revive him, it was a visitor who had to call 911.

The issues aren’t unique to one or two clinics, the patients and workers said. Problem clinics aren’t all run by a particular company, they said, and good clinics aren’t the province of certain companies either. But it’s the bad examples, especially when it comes to worker schedules, that have led to calls for reform.

“Here’s a highly consolidated industry with two major corporations and $2 billion in profits. Also in which there have been pretty well-documented problems with the quality of care.” — Ken Jacobs, chairman Labor Center at the University of California-Berkeley

Dialysis, which treats patients with advanced kidney disease, is lifesaving. The question is whether California’s ballot initiative to limit the profit of dialysis clinics, Proposition 8, would be more likely to protect lives or end them.

“It is disheartening for the bill to put these people in danger of dying,” Thomas said, referring to the referendum. Thomas had her first dialysis when she was only 16. She’s had one kidney transplant since, but it failed. She’s back on dialysis waiting for a new organ.

At her clinic, she says everyone “is taking care of me; they show me so much love.” She says she thinks the ballot measure would mean cutbacks and clinic closures that would hurt her treatment.

By contrast, Foster says the current system, without the proposed changes, is what worries her. She’s afraid that overworked technicians might get sloppy and give improper care, which can be fatal to patients like her. “Knowing you can kill people is one thing, being the person you can kill is another,” she says, tartly. The stakes for the vote on Proposition 8 are enormous, especially for the dialysis industry, which served more than 139,000 patients in the state last year.

The number of kidney disease patients in the state rose 46 percent from 2009 to 2016, mostly because patients are living longer, according to the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. In that time, 123 new dialysis centers were opened in the state, mostly by DaVita and Fresenius, the two largest dialysis companies nationwide.

‘Direct Patient Care’

The ballot initiative, which was spearheaded by the Service Employees International and the United Healthcare Workers Unions, would require dialysis clinics to issue refunds to patients or insurance companies if they have revenue above 115 percent of the costs of “direct patient care,” which includes wages and benefits of staff who administer treatment to patients, as well as drugs and supplies.

While the initiative does not spell out a requirement that clinics reinvest in workers, via higher wages and better working conditions, that is clearly the hope of union organizers.

A similar initiative is being pushed in Ohio, also by unions. The Ohio initiative likewise would limit profits to 115 percent of patient-related expenses. That effort initially fell short of the number of signatures required to make the ballot, but was granted an extension. The group has turned in more signatures to state officials and is waiting to see whether enough will be certified.

The dialysis industry views the California and Ohio efforts, apparently the first of their kind, as canaries in a coal mine. They fear that if such initiatives pass, they could spread throughout the country and severely affect their business, and by extension, patients.

Kidney dialysis patients are living longer and more patients are coming into the system as incidences of diabetes and high blood pressure, both precursors to kidney disease, increase.

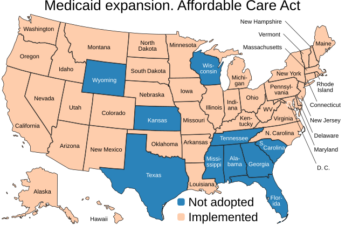

But backers of the initiatives point to profit regulations for health insurance companies included in the Affordable Care Act as their model for regulating the income of big providers. The ACA created a minimum “medical loss ratio” standard for insurers, which required a company to spend 80 to 85 percent of premium income on medical care, leaving the remaining for profit. The initiatives’ language mirrors the ACA’s.

Campaign Finance

The two largest dialysis companies, DaVita and Fresenius, both reported strong quarterly earnings in the second quarter of this year.

“We are working with a broad coalition of over a hundred health care providers and patient groups to oppose these measures and intend to do whatever is necessary to educate voters on why these measures are flawed,” said DaVita Kidney Care CEO Javier Rodriguez during a call with investors this month, as reported by the trade journal Nephrology News and Issues. “Unfortunately, educating voters on regulations around a complex and lifesaving therapy such as dialysis will be expensive.”

A spokesman for the SEIU-United Healthcare Workers West, Sean Wherley said, “This is an industry that will skimp on care to send a windfall to their shareholders.” As an example, he maintained some clinics don’t provide face covers for workers or don’t replace them when they get scuffed. “They are getting cheap with an illness where their lives are on the line every time they walk into a clinic.”

Nothing could be further from the truth, according to Kathy Fairbanks, spokeswoman for a coalition of mostly dialysis companies that opposes Proposition 8, “Patients and Caregivers to Protect Dialysis Patients.”

Fairbanks insisted that limiting profit margins would force clinics into the red and, ultimately, to close, thwarting the hopes of the labor unions. She said the initiative puts patients’ lives in jeopardy because “it sets really low limits on what private insurance companies will be required to reimburse dialysis clinics,” making it hard to recover costs and even harder to stay open.

“The group behind this initiative is promoting this as being good for patients, but in the end, it’s not good for patients if they don’t have access to dialysis that they need to survive,” she said, adding that clinic closures would require patients to travel longer distances to find care, adding even more time to their treatment. The dialysis process, which removes toxins from the blood when the kidneys do not work properly, takes on average 3 to 4 hours a day, three days a week.

There are also questions about whether administrative costs such as human resources and payroll spending could be included under the “direct patient costs” allowed under the proposition. The industry says they would not be, making it hard for them to turn a profit. A study by the Berkeley Research Group, a private consulting firm with conservative roots, estimated only 69 percent of actual costs would be covered under the measure.

But there’s little question that the dialysis business is a profitable one. In 2016, DaVita reported operating profit margins of 12.8 percent and Fresenius reported 14.7 percent. By comparison, hospitals in California generally had profit margins of about 6.8 percent in 2015, according to the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development.

The two companies have raised $18 million to fight the initiative, according to Ballotpedia, which tracks referendums and initiatives. Supporters, led entirely by unions, have raised $6 million.

Labor Unions Dialed In

Starting pay for kidney dialysis technicians is around $14 to $15 an hour. Emerson Padua, 43, a 20-year veteran dialysis worker in Southern California, said he makes less than $23 an hour. He notes the proliferation of clinics, mostly opened by the big companies, indicates that they are profitable and could probably afford to pay their workers more.

There were 420 clinics in California in 2009, according to California HealthLine, a product of Kaiser Health News. By 2017 the number had reached 584, the California Office of Health planning and Development said in an email. “In reality, they are like McDonald’s now,” Padua chuckled.

The chairman of the Labor Center at the University of California-Berkeley, Ken Jacobs said that a few major players have consolidated the highly profitable industry, which, combined with labor unions’ desire to unionize dialysis workers, has played a part in spearheading the initiative.

“Here’s a highly consolidated industry with two major corporations and $2 billion in profits,” Jacobs said. “Also in which there have been pretty well-documented problems with the quality of care.”

The nonprofit news outlet ProPublica did an investigation in 2010 that found U.S. dialysis treatments are costly and riddled with lapses in sanitary conditions and care. Because “end-stage renal disease” qualifies for Medicare coverage, regardless of the patient’s age, dialysis and related treatments make up 6 percent of the Medicare budget. ProPublica reported that was more than $20 billion a year. And that doesn’t count the number of patients who have private insurance.

Shortly after the ProPublica report, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the government agency that runs the medical programs, came up with new standards and accountability ratings for dialysis centers.