By Ashley Bullock

Public Health – Seattle & King County

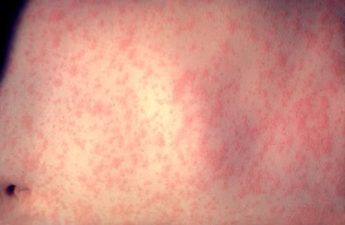

Also known as rabbit fever or deer fly fever, tularemia is a rare disease caused by infection with the bacterium Francisella tularensis. It can range from mild to life-threatening, causing ulcers, gland inflammations, and in some instances, difficulty breathing. In King County, only seven cases of tularemia have been reported to Public Health over the past ten years, four of which had no travel outside of the County during the time they were likely exposed.

Based on its nicknames, it’s not surprising that these bacteria favor rabbits, hares, ticks, and deer flies, all of which abound here in Washington State. Although cases can occur at any time of the year, risk of infection increases in summer months when bites from ticks and flies are more common and people spend more time doing outdoor activities that might expose them to the bacteria.

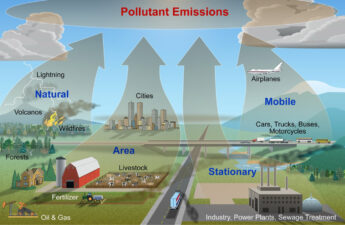

Tularemia is a vector-borne and zoonotic infectious disease (meaning it can be transmitted to humans by animals or vectors, like ticks and deer flies, but not from human to human). In fact, more than 200 species of wild and domestic mammals are susceptible to infection!

Humans can become infected with the bacteria that causes tularemia in a number of ways, and the symptoms that develop depend on the route of infection:

- Bug bites. Ticks and deer flies tend to be the most common culprit when it comes to tularemia infections via bug bites. But lots of other bugs can also carry the bacteria.

- Handling infected animals. People can become infected via the skin through touching an animal that is infected with the bacteria. This most commonly happens when hunting or skinning infected rabbits or rodents. However, domestic cats are also susceptible and have been known to pass the infection to humans.

- Breathing in bacteria. Gardening, mowing, and other landscaping activities can kick up dust containing the bacteria left behind in dirt or grass by an infected animal, which can then be inhaled. This can also happen when mowers run over infected animals.

- Ingestion of contaminated water or food. This tends to be the least common way people get sick from the bacteria, but it occasionally happens when someone eats undercooked meat from an infected animal or drinks contaminated water.

- Laboratory exposures. Laboratory workers may be exposed if special precautions are not taken when handling culture specimens growing tularemia.

Thankfully, you do not have to outright avoid the cute, fluffy rabbits when out hiking in order to prevent tularemia, you just need to take a few precautions to protect yourself. Prevention strategies for tularemia are simple and are in line with how you prevent other zoonotic diseases.

- Protect yourself from bug bites. Use insect repellent and wear long sleeves and pants when out in areas where ticks or deer flies are common. Also, make sure to check yourself for ticks often and remove any you find with fine-tipped tweezers as quickly as possible.

- Be aware when mowing or gardening. Before mowing, check the area for sick or dead animals and avoid mowing over them. Also, wearing a mask might reduce the risk of breathing in the bacteria but this hasn’t been studied.

- Take precautions when handling animals. Keep cuts and other wounds covered and wear gloves when handling dead animals, especially our main offenders, rabbits, hares, and rodents. If you are a hunter or trapper, cook wild meat to a minimum temperature of 165 F and wash your hands thoroughly after touching raw meat.

If you think you’ve been exposed and develop symptoms of tularemia, contact your health care provider. Make sure to tell them about the potential exposure, such as a tick bite or contact with an infected animal, so that they can get you the care you need. Tularemia is treated with antibiotics, and most patients completely recover.

Originally posted on August 3, 2018.