By Elaine S. Povich

Stateline

Todd Weiler, a Republican state senator from Utah, loves to ride bikes on the roads, trails and byways of his home state, including through the picturesque Bryce Canyon. He’s had many road and mountain bikes over the years, including several that he’s crashed and five that were stolen.

But at age 51 and sporting an artificial knee, Weiler now loves his electric mountain bike the most.

He uses his power-assist bicycle to help him climb Bryce Canyon’s hills. But until Weiler successfully passed two bills, one in 2016 and another this year, Utah, like many other states, had a hodgepodge of laws governing bicycles and motorized vehicles, none of which really applied to electric bikes.

Electric bicycle sales in the United States have nearly tripled in the past three years, making them the fastest-growing type of bicycle on the market.

Their surging popularity has outstripped some attempts to regulate them, leading to confusion about their place on the road, conflict with other cyclists, and sometimes hefty traffic fines that threaten the livelihood of those who use e-bikes to do their jobs.

“The problem we were facing with some municipalities is that they were treating all electric bikes as motorcycles,” Weiler said. “Obviously, there’s a difference between an electric bike that I can pedal and get help to go a few miles an hour, and motorcycles that can go 100 miles an hour.”

Weiler wrote legislation that took effect in 2016 that divides electric bikes into three classes, depending on their horsepower, and makes them subject to traffic laws that govern regular bicycles. The law also prohibits people under age 16 from driving the largest motorized bikes, called Class III, and allows local authorities to set rules for the electric bikes.

Earlier this year, the Utah Legislature passed a companion bill banning open alcohol containers from the electric bikes while in use. They had neglected that aspect with the first bill, Weiler said, endangering about $7 million in federal highway funding.

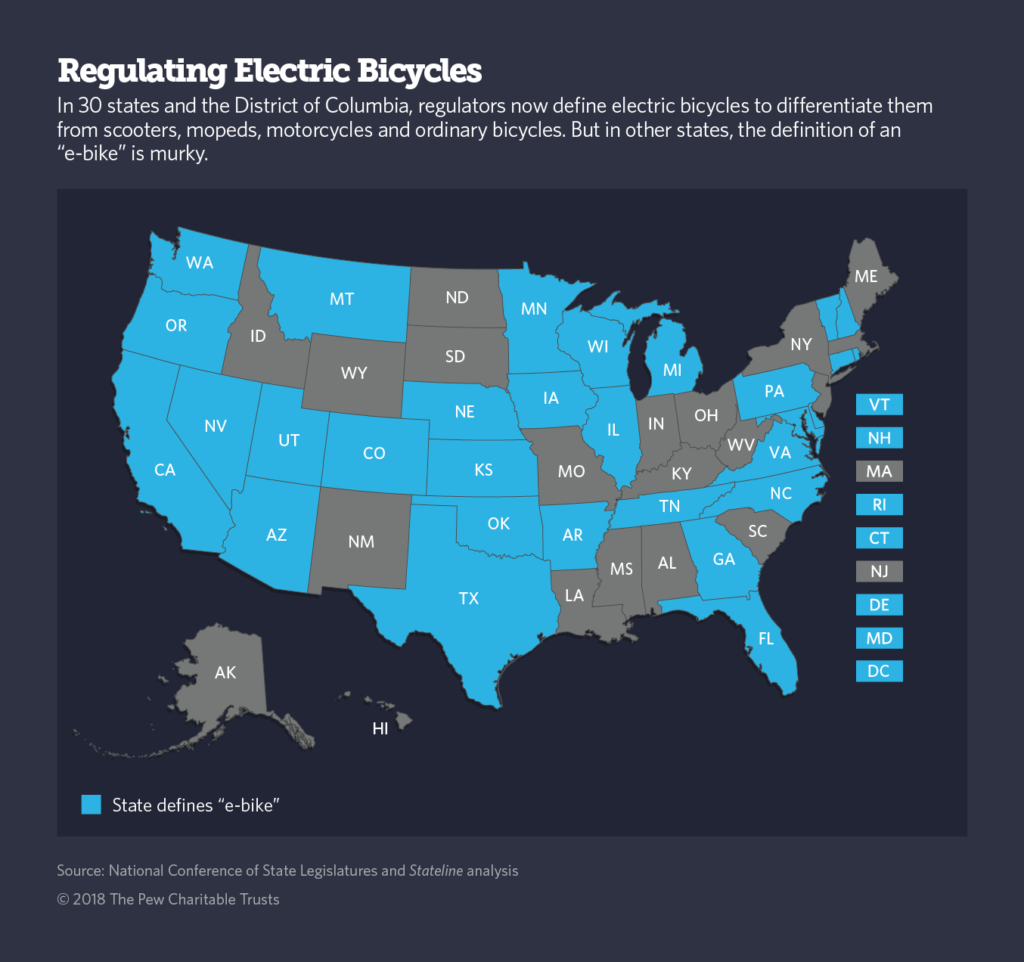

Nine other states have enacted similar laws — three just this year — including Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Michigan, Tennessee and Washington, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Another 20 states have some laws that apply widely, but unevenly, to electric bikes. The rest have no e-bike laws at all.

Lagging Legislation

Technology has gotten ahead of regulation, said John MacArthur, a transportation researcher at Portland State University.

“Every state puts out regulations around motorized devices,” he said, “but some states have had regulations on the books that are appropriate in describing the bikes, while some are using antiquated definitions.”

Those, he said, include laws that describe gasoline-powered motors — an outdated definition since the new e-bikes use rechargeable motors.

MacArthur pointed to New York City as a “classic example” of a place where outdated rules are impeding electric bike use.

In October, Democratic New York Mayor Bill DeBlasio announced a crackdown on electric bikes under a city law that classifies them as motorized scooters, which are not street legal.

Food delivery workers often use e-bikes to carry pizza, Chinese food and other meals, but police officers started handing out fines as high as $500 — which is sometimes equal to the workers’ weekly salary.

New York City councilman Rafael Espinal said he’s readying legislation that would legalize e-bikes in the city. It is discriminatory to fine the city’s delivery people, most of them minorities, he said, for riding the electric bicycles to do their jobs.

MacArthur, the researcher, said e-bikes present the same safety issues as regular bikes: mostly “crashes and older people.”

U.S. research on electric bicycles is sparse, since they are so new, he said, but European researchers have reported older people falling over when they stop the heavier e-bikes because they aren’t used to riding them. “It’s not a crash speeding, it’s a crash standing.”

Studies have shown that e-bikes on average go between two and three miles per hour faster than conventional bikes, MacArthur said.

“You have conventional bikes going faster than people on e-bikes, but you also have e-bikes going faster than people on conventional bikes,” he said. “I have ridden e-bikes where people pass me on the flats. I will pass people on hills.”

Rider Rivalries

The debate over e-bike regulation has spilled over into similar conversations surrounding the recent trend of electric scooters zipping around cities.

Both modes of transportation have now been adopted by rent-by-the-hour companies, further complicating their regulation as cities also must grapple with where the bikes can be left (on the sidewalk or not), or whether they must be docked after use.

Some people don’t like the scooters, so much so that they are setting them on fire, burying them in the sand or dumping them in the ocean, the Los Angeles Timesreported. People haven’t turned on e-bikes in the same way.

Aside from those who use the electric bikes for work or commuting, many riders say e-bikes are fun for recreation.

In Utah, Weiler said he uses an electric mountain bike on trails in Park City and Moab, but he has encountered officials and other riders who are hostile to the electric versions.

“It sounds like discrimination,” he said. “If you are fit enough to pedal up the hill, you can go, but electric bikes can’t. I’m not sure I’m okay with saying that every trail in a city can be pedal only.”

Cities are going to have to work out rules that accommodate all kinds of riders, he said. In addition, regular bike riders sometimes say to him, “We don’t want you up here,” as he rides his electric bike — a declaration he thinks is unfair.

There are some rivalries between electric bikers and regular bike riders, conceded Ron Tripp, of Chevy Chase, Maryland, the chairman of a bicycle trail association, who was waiting outside a Washington, D.C., bicycle shop for a Potomac Pedalers group, getting ready to ride on a summer evening.

Some of the riders on motorized bikes “really fly up the trail,” he said. “If they would ride like the others, at about 15 miles per hour, there would be no problem. They do need legislation that should accommodate them properly.”

Charlie McCormick, owner of ElectriCityBikes, an offshoot of City Bikes, which has been in business for 30 years in the District, said the pedal-assist bikes are flying out of his store. They might not provide the same aerobic workout as ordinary bikes, he said, but they do contribute to overall fitness because they get less fit people out of their chairs.

“Clients use the e-bikes to get fit,” he said, “because you can choose to dial back the assistance level.”

McCormick and Weiler also mentioned an aspect of the e-bikes that may be making them more popular than ever: keeping friends and couples together.

Usually, they said, one member of the couple is an avid cyclist — but the other, not so much — so they can only ride together when one has a little lift from an electric motor.

“We see that a lot,” McCormick said. “I call the e-bikes ‘the equalizer.’”