Survey Offers Hospital Biobanks a Lesson in Gaining Patient Trust

The more than 5 million people who paid to get their DNA analyzed by the company 23andMe recently found out that their genetic data and related health information might have been sold to a major drug company.

That’s because 23andMe made a $300 million deal with GlaxoSmithKline allowing the pharmaceutical giant to tap that genetic gold mine to help develop new medicines. Because 80 percent of 23andMe customers consented to allow their DNA samples to be used for research when they sent them in, their data can be sold in this way unless they opt out.

Millions more people have samples sitting in very different kinds of biobanks: ones at universities and major teaching hospitals. When patients have surgery, biopsies or blood draws at hospitals, those specimens may be kept for future research.

But the parameters are different here: If the specimens in academic biobanks don’t include patients’ identifying information, researchers don’t need informed consent from the patient to keep the samples for research.

A new University of Michigan survey examines public attitudes toward potential commercial use of these samples, even when they aren’t attached to a patient’s identifiable information.

The survey, published in a paper in the August issue of Health Affairs, reveals what people think about such arrangements and what they would want to know if their de-identified specimens were part of one.

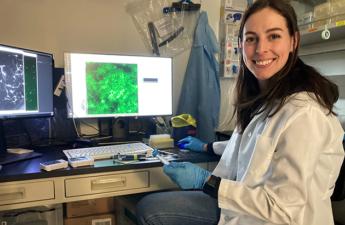

The effort was conducted by bioethics researchers from U-M’s Medical School and School of Public Health.

Refining the process

When it comes to commercialization of academic biobanks, the majority aren’t on board. Only 1 in 4 of the 886 people surveyed nationally said they’d be comfortable with companies getting access to their leftover specimens from a university or hospital biobank.

And two-thirds of respondents said that if such a deal happened, they’d want to know.

However, as Andrew Shuman, M.D., a head and neck surgeon and co-chief of the Clinical Ethics Service of the Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine, points out, “There are compelling reasons to ask for patient consent before we collect specimens for research — whether or not their identifiable health information is included.”

Nonprofit institutions such as academic medical centers typically use these samples for research. But often they need to look elsewhere for funding to support the upkeep of the biobank, prompting them to sell access to private companies through commercialization.

“That’s a big part of the business model of the direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies,” says Michele Gornick, Ph.D., a U-M faculty member and the study’s co-author. Still, she notes, it was not the driving force behind the creation of academic biobanks.

As more academic institutions seek to commercialize their biobanks, the U-M team asked survey respondents what universities and hospitals should do with the money from such deals.

Sixty-two percent said they should put those funds back into more research. Which is why the U-M team argues in the article that these findings demonstrate that when asking for informed consent to biobank donation, researchers should disclose what the money will be used for.

“[I]f you disclose commercial interests, people are less likely to participate. But if you also tell them that the money will be reinvested in research, this will re-engage trust and encourage participation.” — Jodyn Platt, Ph.D.

Building trust and participation

The findings have real-world implications, says Jodyn Platt, Ph.D., the study’s senior author and assistant professor at the medical school.

They suggest that institutions should go above and beyond what the law requiresunder the newly revised Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, or “Common Rule,” that takes effect in January 2019.

Under the new regulations, public biobanks will often be required to disclose to patients if specimens will be commercialized.

“The new disclosure laws are supposed to be a floor, not a ceiling,” says lead author Kayte Spector-Bagdady, J.D., M.Bioethics, chief of the Research Ethics Service at the Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine.

“But it may be counterintuitive for biobanks to disclose more information than legally required. Here, we found that they should be doing just that.”

In any case, greater transparency is key. “We found that if you disclose commercial interests, people are less likely to participate,” Platt says. “But if you also tell them that the money will be reinvested in research, this will re-engage trust and encourage participation.”

The survey, done as part of a larger one led by co-author Sharon Kardia, Ph.D., of the U-M School of Public Health, and also with U-M medical school faculty member Raymond De Vries, Ph.D., included a nationally representative sample of adults who were presented a scenario about biobanking and commercialization and then answered questions online.

Spector-Bagdady, Platt, Shuman and Gornick are members of the U-M Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation.