By Jenni Bergal, Stateline

By Jenni Bergal, Stateline

New Year’s Eve usually is an upbeat time for Salt Lake City restaurant owner Hoang Nguyen. But this year, she’ll be worrying about a big change in the state’s DUI law that she says could put a damper on her business.

On Dec. 30, Utah will become the first state to make it illegal to drive with a blood alcohol level of .05 or higher, rather than the .08 standard that every other state and the District of Columbia use. That means Utah will have the strictest DUI law in the nation.

Nguyen, whose family-owned company, Sapa Investment Group, owns eight restaurants and bars in the Salt Lake Valley, fears that the lower threshold will drive away some customers or prevent them from ordering any alcohol out of fear of being nabbed for driving under the influence.

“A lot of restaurant owners are very unhappy,” Nguyen said. “For us, we’re especially concerned about tourists and business people who come to town and will be afraid to have a drink or two with their meal because they’re going to be .05.”

Despite being denounced by the restaurant and hospitality industry, some traffic safety advocates and a federal highway safety agency support the change to .05 and have been recommending it for years.

Utah is the test kitchen, though it isn’t the only state that has taken up .05 legislation. This year, New York and Delaware considered such measures, as did Hawaii and Washington last year. None of those bills got anywhere, but both supporters and opponents expect legislators in some states will be proposing .05 measures in 2019.

Opponents call the .05 law overkill. They say it targets the wrong group of responsible drinkers and will hurt small businesses and tourism.

Supporters say lower limits will deter drunken driving and save lives. Many industrialized countries, including Australia, France and Italy, already have a .05 or lower standard. Hungary and Romania are among those that have a 0.00 level.

“We support all states moving to a .05 or lower BAC level,” said Maureen Vogel, spokeswoman for the National Safety Council, an Itasca, Illinois-based organization focused on eliminating preventable deaths. “These aren’t just numbers on a page. These are human beings who are not coming home to their families at the end of the day because someone made a poor decision to get behind the wheel after they’ve been drinking.”

Tougher Standards

Congress in 1982 began offering transportation grants to states that set their legal blood alcohol level at .10, and even more money to those that lowered it to .08. Utah and Oregon were the first states to move from a .10 legal blood alcohol level to .08 in 1983. Several years later, the federal government began advocating for the threshold to be lowered to .08 based on scientific research about impaired driving, and other states began to adopt it, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

In 2000, after much controversy, Congress passed a bill signed into law by President Bill Clinton that required states to have a .08 standard by 2004 or start losing federal highway funds. By 2005, every state and the District of Columbia had passed the .08 limit.

Typically, police conduct field sobriety and breathalyzer tests to determine whether a driver is impaired. The blood alcohol content (BAC) depends on a number of factors, including age, sex, weight, how many drinks were consumed, the amount of food eaten beforehand and how much time has passed since the first drink.

Supporters and opponents of lower BAC levels offer conflicting statistics about the effects of alcohol. Traffic safety advocates point to a reference from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that estimates a 160-pound man can hit .05 after about three drinks. They also cite academic research that confirms those numbers and shows that a 130-pound woman can reach .05 after two drinks.

Opponents to lowering the BAC level cite different academic research that shows a 120-pound woman can hit .05 with little more than one drink and a 160-pound man with two drinks.

In 2017, 10,874 people were killed in crashes involving an alcohol-impaired driver, according to the federal highway safety agency. That’s nearly 30 percent of the total 37,133 traffic fatalities that year.

Traffic safety advocates say they want that number eventually to get to zero and many think dropping the BAC standard to .05 is one way to help get there.

About 100 countries have BAC levels of .05 or lower, according to the National Transportation Safety Board, and while their average consumption is the same or higher than the United States, their alcohol-related crash deaths are lower.

In the Netherlands, for example, where alcohol consumption is higher than the United States, 19 percent of crash deaths were alcohol-related in 2017, compared with 31 percent in the United States.

“At .05 you start to see driving skills become severely degraded,” said Tara Gill, state programs director for Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety, a nonprofit road safety group. “You’re looking at reduced coordination and ability to track moving objects. There’s difficulty steering and reduced response to emergency driving situations.”

Gill said lowering the legal BAC level will have a broad deterrent effect, and other states should follow Utah’s lead.

“Lowering the BAC to .05 does not necessarily result in more arrests. It’s a behavioral change,” she said. “Somebody who may have had three drinks may now only have two. Some people will choose not to drive after drinking. There are a lot of options for people to get home safely, like taxis, Uber and Lyft.”

Heated Debate

Utah legislators passed the .05 DUI measure last year, but gave it more than a year and a half to go into effect to allow time for law enforcement training.

The debate was contentious, with protesters from the hospitality industry rallying in the state Capitol and safety advocates making impassioned pleas about victims of drunk drivers and how lives could be saved with the stricter BAC rule.

Republican state Rep. Norm Thurston, the bill’s sponsor, said it ultimately passed because legislators were convinced it would reduce drunken driving fatalities across the board.

“We had science on our side,” Thurston said.

One academic study by researchers at the University of Chicago and the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation found that dropping the BAC from .10 to .08 in the United States had reduced alcohol-related driving fatalities by 10 percent from 1982 to 2014. The researchers published another study that reviewed international research and concluded that dropping the BAC from .08 to .05 or lower cut fatal alcohol-related crashes by 11 percent. If every state adopted a .05 limit, researchers said, it would save an estimated 1,790 lives a year in the U.S.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine supports the .05 standard, as does the National Transportation Safety Board, which in 2013 recommended that every state lower its level from .08 to .05.

The transportation safety board’s then-vice chairman, T. Bella Dinh-Zarr, even went to Utah to testify at the House and Senate committee hearings and meet with individual members to offer her agency’s support for the .05 standard.

“I think that turned the tide,” Thurston said.

Pre-Hearing Mimosas

Utah state Sen. Jim Dabakis, a Democrat who strongly opposed the legislation, said he thinks it’s going to make Utah a laughingstock.

“It’s draconian. It’s a catastrophe,” Dabakis said. “There’s absolutely no evidence that this is going to do any public safety good. Instead, it has the potential to take thousands of innocent non-drunk people, declare them as DUI and put them on the fast track to all the criminal justice consequences of a DUI.”

Dabakis sponsored his own bill this year to try and delay the .05 law until three other states passed a similar measure.

He arrived to testify at the February committee hearing after drinking two mimosas with breakfast (a staffer drove him to the Capitol) and announced he had blown a .05 on a breathalyzer. The point, he said, was to show that his presentation wasn’t affected by the alcohol. His bill failed.

Industry Opposition

One of the biggest opponents of .05 legislation — in Utah and elsewhere — is the American Beverage Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based trade group for restaurants that sell alcohol.

Communications Director Jackson Shedelbower said the vast majority of alcohol-related fatalities involve drivers with very high BAC levels. States should be focused on them and on repeat offenders, he said, and should improve their enforcement of ignition interlock laws.

Dropping the standard to .05 is a bad strategy, Shedelbower said, and will not have a broad deterrent effect on dangerous drinkers.

“Why would someone who already is breaking the law driving well above the .08 BAC all of a sudden not drink too much and drive if the law was lowered to .05?” he said. “We think the impact will actually be on moderate, responsible drinkers — the couple who shares a bottle of wine with dinner or someone who goes to happy hour with a co-worker and has a drink.”

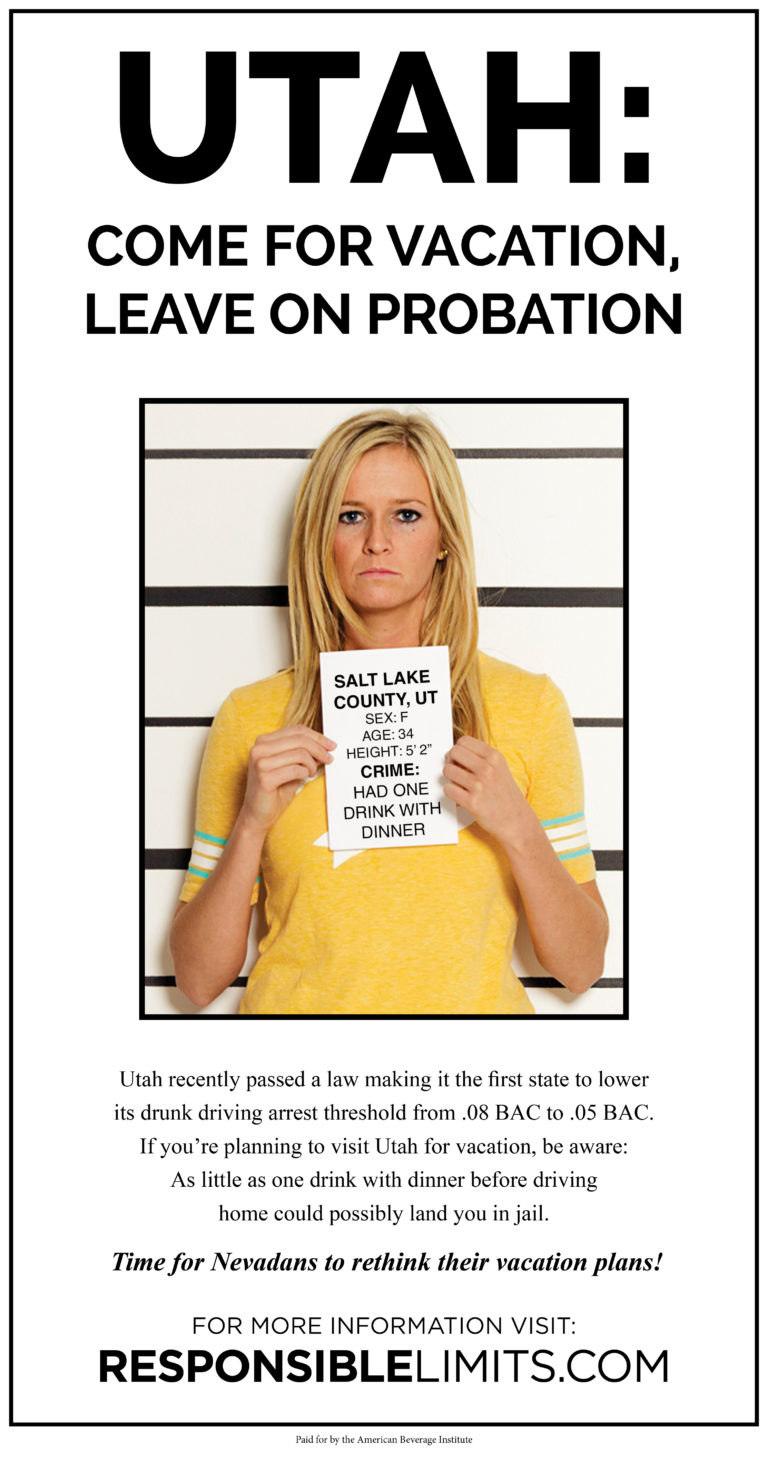

During the Utah debate, Shedelbower’s group took out full-page ads in newspapers in Utah, neighboring states and national publications. One showed a woman in a fake mug shot that read: “Utah: Come for vacation, leave on probation.”

In Utah, alcohol sales through state-owned and -operated liquor stores, which sell bars and restaurants all their alcohol, have been rising rapidly. Sales jumped from nearly $329 million in fiscal 2013 to about $454 million in fiscal 2018, according to Terry Wood, a Utah Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control spokesman.

But restaurants and bars are bracing for a loss in alcohol revenue because of the new law, said Michele Corigliano, executive director of the Salt Lake Restaurant Association, a trade group for independent restaurants and bars.

Corigliano and some other critics say the measure only passed because a large majority of the Utah legislature is Mormon.

“Many of these Mormon legislators have never had a drink so they don’t understand what it feels like,” she said. “They think all drinking is bad.”

Rep. Thurston, a Mormon who said he doesn’t drink, dismisses that argument.

“I have never thought it was a Mormon thing. It’s a public safety thing,” he said. “On this policy issue, it doesn’t have anything to do with the drinking. It’s about the driving.”

Nor does Thurston buy the argument that restaurants and bars are going to take a hit.

“People are not going to change their drinking,” he said. “They’re just going to drive less.”

Stateline is a nonpartisan, nonprofit news service of the Pew Center on the States that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy.

Stateline is a nonpartisan, nonprofit news service of the Pew Center on the States that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy.