By Nathan Lachowsky, University of Victoria and Gbolahan Olarewaju and Heather Armstrong, University of British Columbia

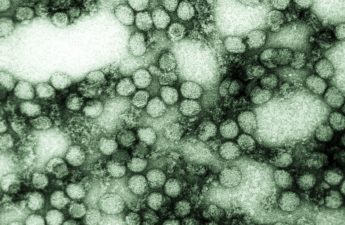

More than 60,000 Canadians, 1 million Americans and 37 million people worldwide are living with HIV. In the early days of HIV and AIDS, there was enormous fear and discrimination — to the extent that in British Columbia politicians debated quarantining individuals with HIV.

Since then, the arc of scientific progress on HIV has been swift. But HIV-related stigma and discrimination are not gone and the global epidemic is far from over.

There are still 2,000 new cases of HIV in Canada each year. Fundraising for AIDS service organizations has slowed and global funding for HIV research and development has declined.

This World AIDS Day we call for recognition that negative judgment and feelings about HIV are intertwined and tangled up with racism, transphobia and homophobia.

You can have HIV and become ‘untransmittable’

Due to access to modern antiretroviral treatments, HIV has become for most a manageable condition. Research from the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS (BC-CfE) has demonstrated that people with HIV who are taking treatments now have a similar life expectancy to those who are HIV-negative.

Julio Montaner, Director of the BC-CfE, pioneered the concept of ‘treatment as prevention’ (TasP). The medical and scientific community has come to consensus that an individual living with HIV can become “untransmittable” — meaning there is no risk of them sexually transmitting the virus — if they achieve an undetectable viral load through HIV treatment. People living with HIV have led the “undetectable = untransmittable” movement to share this message of hope and to fight against HIV stigma.

According to our own research on the Momentum Health Study, the number of HIV-negative gay men in Vancouver who knew this concept nearly doubled from 2012 to 2015. The good news is that this wasn’t associated with any decreases in condom use.

The bad news: Key messages about HIV prevention and testing may not be reaching all audiences. For example, we found that bisexual men, older men and men living outside of the city were significantly less likely to have been tested for HIV in the past two years.

Unfortunately, efforts to stop the spread of HIV are hindered by fear and stigma. For instance, some gay and bisexual men never get tested for HIV because they worry about the impact it might have on their relationships and sex life, and that they may face discrimination.

Men still fear telling doctors and getting tested

In Canada, it remains a criminal offence not to disclose one’s HIV-positive status in consensual sex if a condom is not used.

This discriminatory law remains despite the now strongly established scientific consensus that an individual with an undetectable viral load cannot transmit the virus. This was proven through a study in which nearly 60,000 acts of condom-less intercourse between serodiscordant couples (where one partner is HIV negative and the other is HIV positive) did not result in HIV transmission.

These fears also make it difficult for men to tell their doctor about sex with other men. At least a quarter of Momentum participants had not told their doctor about having sex with men, and those men were half as likely to have been recently tested for HIV.

Stigma also affects access to services and mental health. Men who experienced more mental challenges (depression and use of multiple illicit drugs) were more likely to engage in sex that could pass HIV.

Feelings of disassociation from the disease can be intertwined with discrimination. For example, HIV risk among trans men in the Momentum Health Study was shaped by difficulty in safely finding sexual partners, challenges with condom use and barriers to accessing health care including transition-related services.

There is an effective HIV-prevention drug

We now have more tools in the HIV prevention toolbox than at the peak of the epidemic. Safer sex, which once referred to condoms alone, now considers issues such as undetectable status and pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP.

The HIV prevention medicine PrEP is highly effective when taken consistently and is available at no cost to eligible HIV-negative individuals in British Columbia who are at high-risk of HIV.

Prior to PrEP being covered in B.C., only 2.3 per cent of gay men in the Momentum Health Study in Vancouver had used PrEP. However, the awareness of PrEP more than quadrupled to 80 per cent from 18 per cent during this period.

Although challenges to access remain, thousands of gay men and other people at risk of HIV across B.C. now take PrEP free of charge.

HIV has changed. And our perceptions need to catch up. Now is the time for policymakers, service providers and the country as a whole to embrace a better understanding of HIV.

Complacency, ignorance and continuing to see HIV as something shameful will keep us from advancing in our efforts to support people living with HIV and reduce new infections.![]()

Nathan Lachowsky, Assistant Professor, School of Public Health and Social Policy, University of Victoria; Gbolahan Olarewaju, Momentum Study Coordinator at the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, University of British Columbia, and Heather Armstrong, Momentum Postdoctoral Fellow, BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Read the original article.