When Patrick Mannion heard about the Michigan woman denied a heart transplant because she couldn’t afford the anti-rejection drugs, he knew what she was up against.

On social media posts of a letter that went viral last month, Hedda Martin, 60, of Grand Rapids, was informed that she was not a candidate for a heart transplant because of her finances. It recommended “a fundraising effort of $10,000.”

Two years ago, Mannion, of Oxford, Conn., learned he needed a double-lung transplant after contracting idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a progressive, fatal disease. From the start, hospital officials told him to set aside $30,000 in a separate bank account to cover the costs.

Mannion, 59, who received his new lungs in May 2017, reflected: “Here you are, you need a heart — that’s a tough road for any person,” he said. “And then for that person to have to be a fundraiser?”

Martin’s case sparked outrage over a transplant system that links access to a lifesaving treatment to finances. But requiring proof of payment for organ transplants and post-operative care is common, transplant experts say.

“It happens every day,” said Arthur Caplan, a bioethicist at the New York University Langone Medical Center. “You get what I call a ‘wallet biopsy.’”

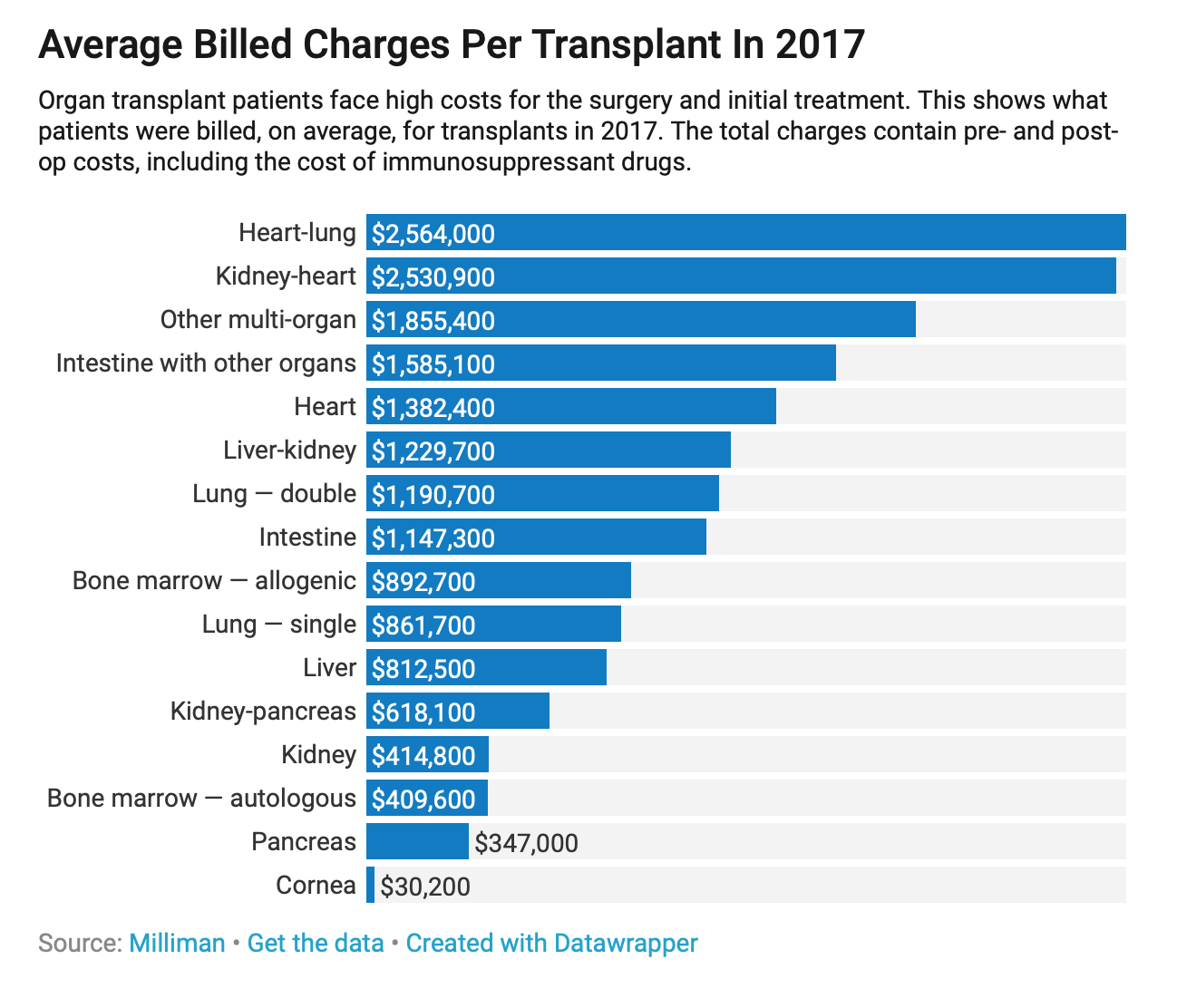

Virtually all of the nation’s more than 250 transplant centers, which refer patients to a single national registry, require patients to verify how they will cover bills that can total $400,000 for a kidney transplant or $1.3 million for a heart, plus monthly costs that average $2,500 for anti-rejection drugs that must be taken for life, Caplan said. Coverage for the drugs is more scattershot than for the operation itself, even though transplanted organs will not last without the medicine.

For Martin, the social media attention helped. Within days, she had raised more than $30,000 through a GoFundMe account, and officials at Spectrum Health confirmed she was added to the transplant waiting list.

In a statement, officials there defended their position, saying that financial resources, along with physical health and social well-being, are among crucial factors to consider.

“The ability to pay for post-transplant care and life-long immunosuppression medications is essential to increase the likelihood of a successful transplant and longevity of the transplant recipient,” officials wrote.

In the most pragmatic light, that makes sense. More than 114,000 people are waiting for organs in the U.S. and fewer than 35,000 organs were transplanted last year, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing, or UNOS. Transplant centers want to make sure donated organs aren’t wasted.

“If you’re receiving a lifesaving organ, you have to be able to afford it,” said Kelly Green, executive director of HelpHopeLive, the Pennsylvania organization that has helped Mannion.

His friends and family have rallied, flocking to fundraisers that ranged from hair salon cut-a-thons to golf tournaments, raising nearly $115,000 so far for transplant-related care.

Allowing financial factors to determine who gets a spot on the waiting list strikes many as unfair, Caplan said.

“It may be a source of anger, because when we’re looking for organs, we don’t like to think that they go to the rich,” he said. “In reality, it’s largely true.”

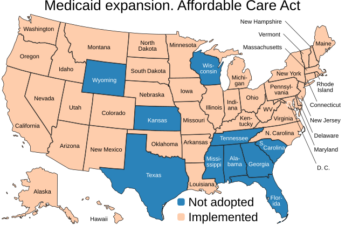

Nearly half of the patients waiting for organs in the U.S. have private health insurance, UNOS data show. The rest are largely covered by the government, including Medicaid, the federal program for the disabled and poor, and Medicare.

Medicare also covers kidney transplants for all patients with end-stage renal disease. But, there’s a catch. While the cost of a kidney transplant is covered for people younger than 65, the program halts payment for anti-rejection drugs after 36 months. That leaves many patients facing sudden bills, said Tonya Saffer, vice president of health policy for the National Kidney Foundation.

Legislation that would extend Medicare coverage for those drugs has been stalled for years.

For Alex Reed, 28, of Pittsburgh, who received a kidney transplant three years ago, coverage for the dozen medications he takes ended Nov. 30. His mother, Bobbie Reed, 62, has been scrambling for a solution.

“We can’t pick up those costs,” said Reed, whose family runs an independent insurance firm. “It would be at least $3,000 or $4,000 a month.”

Prices for the drugs, which include powerful medications that prevent the body from rejecting the organs, have been falling in recent years as more generic versions have come to market, Saffer said.

But “the cost can still be hard on the budget,” she added.

It’s been a struggle for decades to get transplants and associated expenses covered by insurance, said Dr. Maryl Johnson, a heart failure and transplant cardiologist at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

“It’s unusual that there’s 100 percent coverage for everything,” said Johnson, a leader in the field for 30 years.

GoFundMe efforts have become a popular way for sick people to raise money. About a third of the campaigns on the site target medical needs, the company said.

But when patients need to raise money, they should use fundraising organizations specifically aimed at those costs, transplant experts say, including HelpHopeLive, the National Foundation for Transplants and the American Transplant Foundation.

There’s no guarantee funds generated through such general sites such as GoFundMe will be used for the intended purpose. In addition, the money likely will be regarded as taxable income that could jeopardize other resources, said Michelle Gilchrist, president and chief executive for the National Foundation for Transplants.

Her group, which helps about 4,000 patients a year, has raised $82 million for transplant costs since 1983, she said. Such efforts usually involve a huge public-relations push. Still, 20 percent of the patients who turn to NFT each year fail to raise the needed funds, Gilchrist said.

In those cases, the patients don’t get the organs they need. “My concern is that health care should be accessible for everyone,” she said, adding: “Ten thousand dollars is a lot to someone who doesn’t have it.”

Every transplant center in the U.S. has a team of social workers and financial coordinators who help patients negotiate the gaps in their care. Lara Tushla, a licensed clinical social worker with the Rush University transplant program in Chicago, monitors about 2,000 transplant patients. She urges potential patients to think realistically about the costs they’ll face.

“The pharmacy will not hand over a bag full of pills without a bag full of money,” she said. “They will not bill you. They want the copays before they give you the medication.”