By Meredith Li-Volmer

Public Health – Seattle & King County

Five locally acquired cases of hepatitis A infection and an additional case that may also have been acquired locally have been reported to Public Health – Seattle & King County since November 2018.

These cases add to three other hepatitis A cases reported in July 2018 for a total of nine cases in less than a year. Typically, we see no more than five locally acquired cases in an entire year.

We talked to our health officer, Dr. Jeff Duchin, to understand more about this vaccine-preventable disease and how it is spreading in King County.

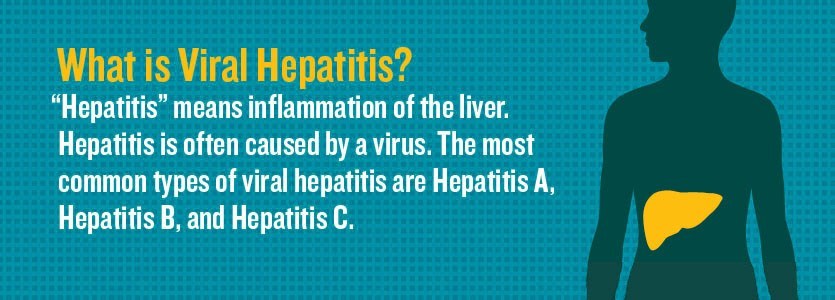

What is hepatitis A and why is it a concern?

Jeff Duchin: Hepatitis A is a highly contagious liver infection that can cause symptoms that range from a mild illness to a severe one lasting several months. On rare occasions, hepatitis A infection can cause liver failure and death. People with underlying liver disease and people who are over 50 years of age are at increased risk for severe hepatitis A infections.

There are nine cases of hepatitis A reported in King County since June. Are any of them linked?

At this stage of the investigation, there are no known connections or common exposures among any of the individuals, but the investigation is ongoing. In hepatitis A outbreaks, direct links between cases are not always identified.

Infections could have spread from contact with people who didn’t know they were infected because they had a very mild illness or never developed symptoms. If they don’t know they’re infected, they don’t get tested and reported to Public Health.

Genetic testing of the hepatitis A viruses shows that three of the six recent cases were infected with the same strain. The virus from another of the six recent hepatitis A cases matches a different strain of hepatitis A and could have been acquired during international travel. Five of the six most recent cases have occurred among gay or bisexual men. One case involved an individual who used injection drugs.

The three cases reported in July 2018 were among females who did not report activities that would put them at increased risk for infection. Two of those cases genetically matched a case in Pierce County and a cluster of five cases in Oregon, but no common source or connections among the cases were identified.

How do the King County cases fit into the picture of hepatitis A outbreaks nationwide?

Since 2016, an increasing number of hepatitis A outbreaks have been reported nationally, especially among people living homeless and among people who inject drugs. About ten percent of new hepatitis A cases nationally occur in gay and bisexual men and there have been outbreaks in other states among men who have sex with men.

None of the cases confirmed in King County have been among people living homeless, although there have been large outbreaks in communities experiencing homelessness in California, Michigan, Utah, and many other states since 2017.

For this reason, we are working with King County healthcare providers to screen patients for hepatitis A risk factors and vaccinate those at risk to help decrease the risk of a future outbreak.

Despite the recent national increase in hepatitis A cases, hepatitis A outbreaks in the US have decreased dramatically since the introduction of a routine childhood hepatitis A vaccination. The vaccine provides long-lasting protection, and since it was made available in 1995, there has been a 95% decline in hepatitis rates.

Who should get vaccinated for hepatitis A?

The best way to prevent hepatitis A is by getting the hepatitis A vaccine. Anyone can get hepatitis A, so the vaccine is important for everyone, but certain groups of people are at higher risk for infection and should be sure to vaccinate. These groups include:

- Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men

- Users of recreational drugs, whether injected or not

- People with unstable housing or who are living homeless

- Travelers to countries where hepatitis A is common

- Family and caregivers of adoptees from countries where hepatitis A is common

- People with chronic or long-term liver disease, including hepatitis B or hepatitis C

- People with clotting-factor disorders such as hemophilia

- People with direct contact with others who have hepatitis A

Hepatitis A vaccine has been part of the routine childhood vaccination schedule in the United States since 2006. Most adults were not vaccinated as children, so everyone should check with their doctor to find out whether they have received the vaccine, and if not, get vaccinated to prevent infection.

The CDC has more information about hepatitis A vaccination and prevention.

How else can you prevent getting hepatitis A?

Hepatitis A usually spreads when a person unknowingly ingests the virus from objects, food, or drinks contaminated by tiny, undetectable bits of stool from an infected person.

Good hand hygiene is important for prevention in case you’ve come into contact with the virus. Always wash your hands with warm water and soap after toileting, changing a diaper, having sex, and before preparing food.

Hepatitis A can also spread through any kind of sexual activity with someone who is infected with hepatitis A virus. Condoms and other measures to prevent STDs do not prevent hepatitis A.

Food can also become contaminated with the hepatitis A virus at many points along the supply chain, so make sure you thoroughly rinse fresh fruits and vegetables before eating and cook seafood, poultry, and meat thoroughly. Avoid cross contamination of cooking surfaces and containers to prevent germs from raw foods from getting into contact with foods that won’t be cooked before eating.

For more information on hepatitis A and for resources for high-risk groups: kingcounty.gov/hepA