By Michael McCarthy

It’s possible to prod immune cells to attack and kill pancreatic cancer cells, according to a report from scientists at the University of Washington School of Medicine and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

Their findings challenge the commonly held view that pancreatic cancer does not elicit an immune system response that is robust enough for immunotherapy to be effective.

“The failures seen in clinical trials with pancreatic cancer have been interpreted to indicate there was a dearth of reactive immune cells — T cells — within the tumor,” said lead author Yongwoo David Seo, a UW Medicine research fellow and surgical resident. “The thinking has been that pancreatic cancer is just not an immunologically ‘hot’ tumor.”

In a paper published April 2 in the journal Clinical Cancer Research, the researchers report that they found such T cells within pancreatic tumors and determined that they can be activated to attack and kill cancer cells. They studied pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, the most common and most deadly pancreatic cancer.

Much of what is known about the immune system’s reaction to pancreatic cancer comes from mouse studies. In this study, however, researchers studied immune-cell behavior in human pancreatic tumor tissue.

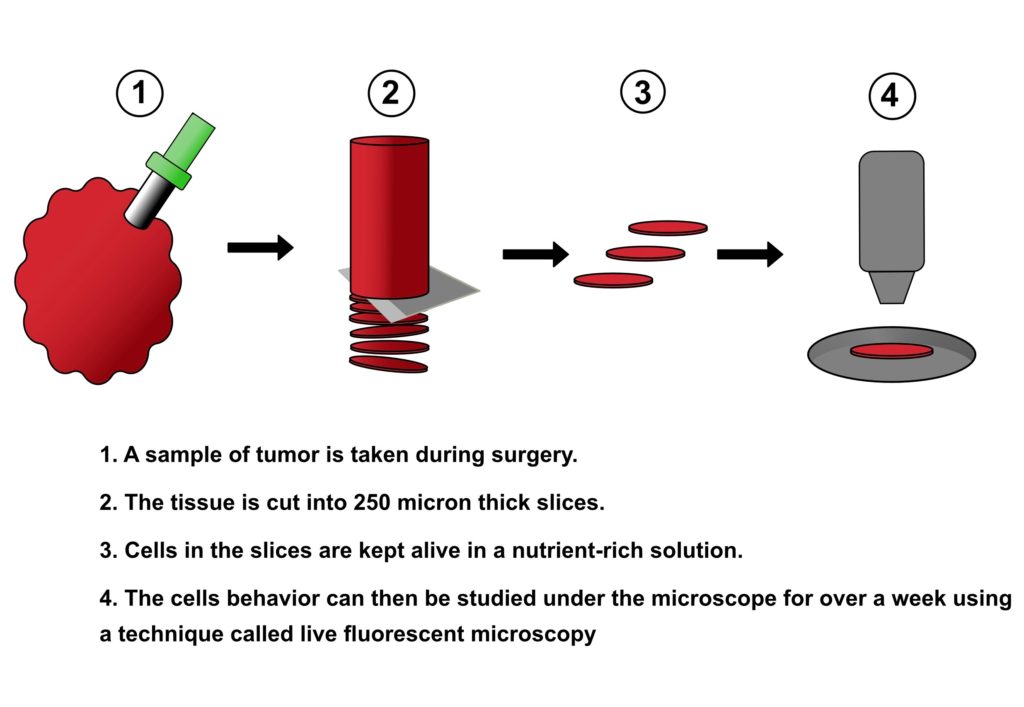

They used small, cylindrical core samples taken from tumors removed during surgery at University of Washington Medical Center.

The cylinders were cut into 250 micron-thick discs that were maintained in nutrient-rich fluid and studied under the microscope for up to one week.

The technique preserved the cellular architecture of the tumor samples and allowed the researchers to observe changes in the immune cells’ interactions with cancer in response to different treatments.

Using this and other approaches, they identified T cells that were primed to attack the tumor cells. What’s more, the T cells in the tumors appeared to have proliferated in ways that suggest they were adapting to react to cancer cells.

“The T cells are responsive and apparently converging on what appears to be important target antigens, honing their attack,” said Robert Pierce, scientific director of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center’s immunopathology lab and co-author of the paper.

The investigators description of “convergent evolution” of T cell receptors reflects that multiple DNA sequences were found encoding for the same protein sequence. They interpreted this as strong selection tendency among those particular T cell receptors, a finding that suggested that those T cells were recognizing immunogenic tumor-associated antigens.

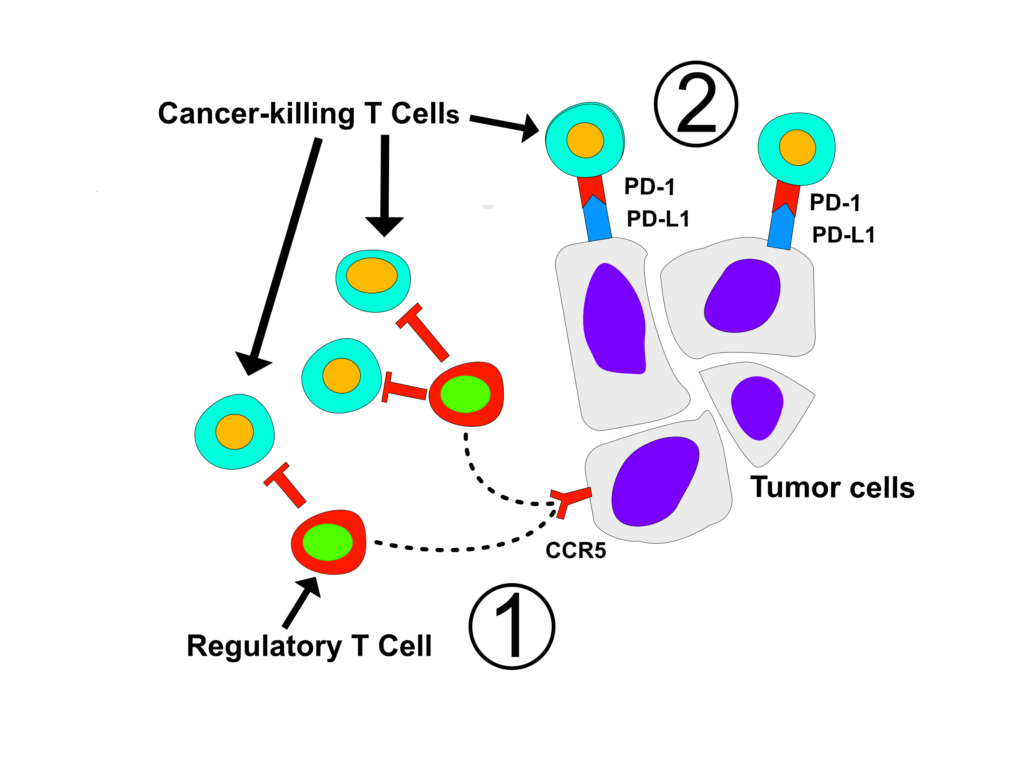

Although the T cells were primed and present, they were not killing the cancer cells. Two things seemed to prevent an effective immune attack: First, the T cells often did not contact the cancer cells, which they must do to kill. Instead, most were located within the tumor’s connective tissue, close to the cancer cells but too far to do them damage. Second, the T cells, though primed to attack the cancer cells, had been inactivated.

The researchers hypothesized that this inactivation was effected by the protein called PD-L1. PD-L1 binds to a protein on the surface of immune cells, called PD-1, which serves as an “off-switch.” Such off-switches are immune-response checkpoints that protect normal cells from inflammation. Many cancer cells, however. target checkpoint proteins to neutralize the immune attack. Cancers can also secrete proteins that inhibit immune cells’ ability to migrate.

To test their hypothesis, the researchers treated human tumor samples with two drugs: an antibody that blocks PD-1 so the cancer cannot stimulate this “off switch,” and a drug called AMD3100, which inhibits CXCR4, a chemokine receptor on immune cells, and which has been shown to mobilize T cells.

“We thought if we could allow T cells to travel to the cancer cells and at the same time take the PD-1 ‘brake’ off, we would get tumor cell death,” Seo said.

They found that after treating the samples with the two drugs, T cells indeed migrated to the cancer cells, proliferated, and killed the cancer cells. It was the first direct evidence of T cell-mediated tumor killing in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, the researchers noted.

Venu G. Pillarisetty, a surgical oncologist and associate professor of surgery at the UW School of Medicine, led the research project. He said the fact that T cell-mediated anti-tumor activity could be stimulated in the tumors from two dozen patients suggests that the two-drug approach may be effective in a variety of patients with pancreatic cancer.

“Our findings suggest that it makes sense to move either this or some similar combination of these drugs into clinical trials,” Pillarisetty said.

Support for this research came from Parvin Valentini Fund for Pancreatic Cancer Research, Donald E. Bocek Endowed Research Development Award in Pancreatic Cancer, United States Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity (CA150370P2), Merck Investigator Studies Program, and Swim Across America.