By Sydney Lupkin, Kaiser Health News

Unraveling how much of a prescription drug price gets swallowed by “middlemen” is at the forefront of Tuesday’s drug price hearing in the Senate. One thing bound to come up: rebates.

Both major political parties have shown interest in remedying high drug prices, and drugmakers have bemoaned how rebates to middlemen keep them from reaping every dollar associated with those price tags.

Pharmacy giant CVS Health criticized the Trump administration’s proposal to end these post-transaction discounts as they apply to Medicare. Yet, in January the company rolled out a Medicare drug plan that experts say is similar “in spirit” to the administration’s proposal.

The CVS Caremark plan wasn’t popular with customers, and CVS Health, which owns CVS Caremark, was quick to point this out as evidence that consumers prefer the current rebate system.

“We had a very, I would say, small number of seniors enroll in that program,” Larry Merlo, CVS Health’s CEO said on a February earnings call with investors. “And we think one of the barriers to that was the increase that we saw in the monthly premium.”

The CVS plan’s premium was $80 a month, which is about double the average Medicare Part D monthly charge. But since it is designed to pass on a portion of rebates directly to patients at the pharmacy counter, certain patients would wind up with smaller out-of-pocket costs than they previously paid.

“Even very well-informed consumers would not necessarily understand that a higher premium plan in this case means that they’re incurring smaller amounts at the point of sale,” said Rachel Sachs, an associate law professor at Washington University in St. Louis who specializes in health care.

So why did only 25,000 people sign up for the plan, called SilverScript Allure? Either consumers didn’t want the plan or perhaps they just didn’t understand it.

We’ll break it down for you.

Untangling Jargon: The Way Things Are And How They Could Change

A pharmacy benefit manager, or PBM, handles drug claims for health insurance companies. The big ones are Express Scripts, CVS Caremark and OptumRx. Every time you fill a prescription and use your drug plan, your PBM is involved in paying the claim and determining how much money you owe the cashier.

A rebate is a discount the PBM negotiates with a drug manufacturer off the price the drugmaker sets, which is called a list price. Rebates are not made public, and they typically don’t get passed on to the patient at the pharmacy counter in the form of a lower copayment, experts say.

When the drugmaker eventually pays the rebate back to the PBM, the PBM often uses this money to lower premiums, which are the monthly fees that Medicare Part D plans charge beneficiaries. They differ for each drug plan.

In a way, patients taking drugs with high list prices and big rebates wind up subsidizing other patients’ premiums, said Erin Trish, the associate director of the University of Southern California Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics. Premiums on average haven’t substantially increased in more than a decade, but it may be “unfair” to the patients paying higher prices for drugs at the pharmacy counter.

“Some may argue, ‘They’re sicker… Maybe they should [pay more],’” Trish said. “Look. We decided everyone should pay the same premium in this market. [Rebates] shouldn’t be a roundabout way to make a subset of beneficiaries pay more.”

That could all change under a new Trump administration proposal that would ban rebates as they exist today. The negotiated discounts would be applied at the pharmacy counter, meaning discounts would be passed on to patients as out-of-pocket costs that are calculated based on the discounted price, not the higher list price.

For patients taking drugs with high list prices and large rebates, like insulin, it could mean noticeable savings, Sachs said. For patients taking drugs without big rebates, like generics or brand-name drugs without other branded competition, they’re not likely to see much change at the pharmacy counter.

Everyone, however, will see premiums go up. It’s unclear yet how much, but Trish said the SilverScript Allure plan CVS Caremark is offering isn’t necessarily the best indicator.

Consultants hired by the Department of Health and Human Services estimated premiums will go up $3.20 to $5.64 per month if the rule takes effect in 2020.

The average Medicare Part D premium for 2019 was $41.21, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

So Why Didn’t Patients Want The CVS Caremark Plan?

It’s not clear how well seniors shopping for drug plans understood the SilverScript Allure plan, among their many options. They could see it had a high premium, but no deductible. They might not have realized it required smaller payments on drugs at the pharmacy counter.

Research shows that the premium is the most important factor seniors consider when choosing a plan, Sachs said.

On top of that, people are unlikely to leave their current plans even if there’s a better one available.

What’s more, we don’t know how well CVS Caremark marketed the plan to seniors who would benefit. They wouldn’t tell us, despite multiple calls and emails.

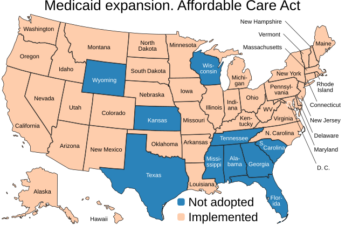

OptumRx, a competing PBM, started offering customers similar discounts at the pharmacy counter — but for people with commercial insurance, not Medicare or Medicaid. Unlike CVS Caremark, it has a web page with basic language, like “point of sale discounts mean lower costs,” and a link to request more information about switching. OptumRx did not respond to a request for comment.

PBMs: Helping Or Hurting?

Rebates for individual plans and drugs are confidential, but in Medicare Part D, they’ve increased on average from 9.6% of total spending in 2007 to 19.9% in 2016, according to annual reports to the Medicare boards of trustees.

So it’s perhaps unsurprising the brand-name drug trade group, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, said it “applaud[s]” the proposal to overhaul the rebate system. PhRMA says it pushes them to raise prices in order to offer larger rebates, because drugs with larger rebates often get preferential treatment by PBMs.

Still, PBMs offer the benefit of batting down net prices (the price after rebate), and keeping down drug spending overall.

There are multiple estimates on how much the rebate proposal would cost the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid if it took effect, and they indicate that unless there are other changes to Medicare Part D, it would likely cost more money than the current system, Sachs said.

“It is startling to see the administration moving forward so rapidly with this proposal without a better understanding of how different actors might respond,” she said. As a result, there’s a “huge amount of uncertainty” over how this could all play out.