By Anna Gorman and Harriet Blair RowanApril 23, 2019

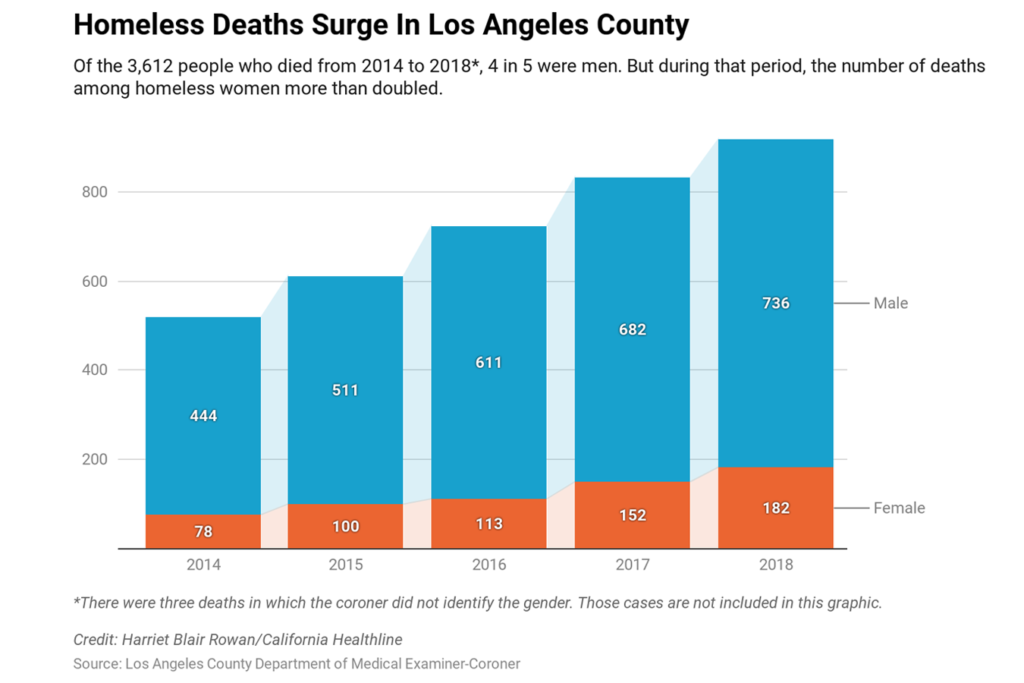

A record number of homeless people — 918 last year alone — are dying across Los Angeles County, on bus benches, hillsides, railroad tracks and sidewalks.

Deaths have jumped 76% in the past five years, outpacing the growth of the homeless population, according to a KHN analysis of the coroner’s data.

Health officials and experts have not pinpointed a single cause for the sharp increase in deaths, but they say rising substance abuse may be a major reason.

The surge also reflects growth in the number of people who are chronically homeless and those who don’t typically use shelters, which means more people are living longer on the streets with serious physical and behavioral health issues, they say.

“It is a combination of people who are living for a long time in unhealthy situations and who have multiple health problems,” said Michael Cousineau, a professor at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California. “There are more complications, and one of those complications is a high mortality rate. It’s just a tragedy.”

Nearly 53,000 people were homeless in L.A. County last year, according to a point-in-time count of homeless residents, an increase of about 39% since 2014. The majority were not living in shelters.

The homeless population has also grown nationwide, but there is no national count of homeless deaths.

The Los Angeles County Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner considers someone homeless if that person doesn’t have an established residence, or if the body was found in an encampment, shelter or other location that suggests homelessness.

Based on that criteria, the coroner reported 3,612 deaths of homeless people in L.A. County from 2014 to 2018.

A detailed look at the numbers reveals a complex picture of where — and how — homeless people are dying.

One-third died in hospitals and even more died outside, in places such as sidewalks, alleyways, parking lots, riverbeds and on freeway on-ramps.

Male deaths outnumbered female deaths, but the percentage of homeless women who died increased faster than that of men. And although black people make up fewer than one-tenth of the county’s population, they accounted for nearly a quarter of the homeless deaths.

“We need to take action now,” said Rev. Andy Bales, CEO of the Union Rescue Mission, a homeless shelter on L.A.’s skid row. “Otherwise next year it’s going to be more than 1,000.”

Substance Abuse

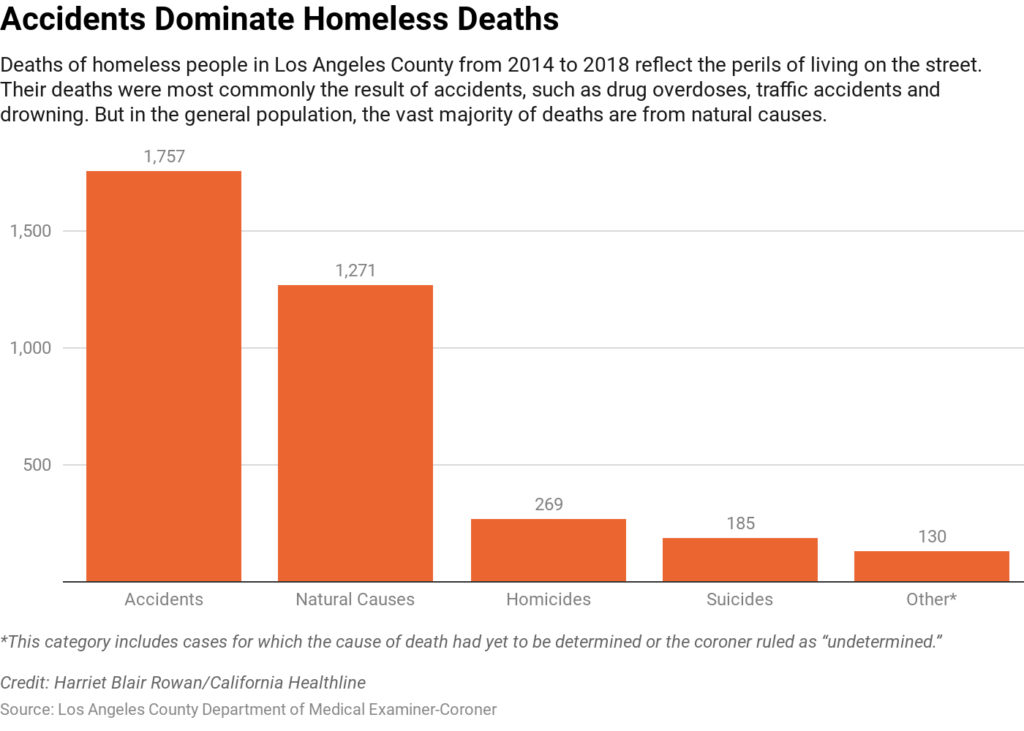

Drugs and alcohol played a direct role in at least a quarter of the deaths of homeless people over the past five years, according to the analysis of the coroner’s data. It likely contributed to many more, including some whose deaths were related to liver and heart problems.

The coroner’s cause of death determination “doesn’t necessarily tell the whole story,” said Brian Elias, the county’s chief of coroner investigations, who called the increase “alarming.”

A person who is homeless may get an infection on top of a chronic disease on top of a substance abuse disorder — and all of those together lead to bad outcomes. “It’s a house of cards,” said Dr. Coley King, a physician at the Venice Family Clinic.

Raymond Thill was just 46 when he died last year of what his wife, Sherry Thill, called complications related to alcoholism. The couple had been homeless for many years before moving into a small apartment in South Los Angeles shortly before his death.

Thill said her husband often drank vodka throughout the day and had been in and out of the hospital because of liver and other health problems. He tried rehab and she tried taking the alcohol away. Nothing worked, she said.

“His mind was set,” she said. “So I took care of him.”

In the end, Thill said, cirrhosis left her husband jaundiced, swollen and unable to keep food down.

King treated Raymond Thill and said he is convinced that Thill would have lived longer if he’d been off the streets earlier.

“This shouldn’t be happening,” especially when many deaths could have been prevented with better access to health care and housing, said David Snow, a sociology professor at the University of California-Irvine. “If you are on the streets, you are not getting the attention you need.”

Dr. Coley King, who treated Raymond Thill before his death, also cares for his wife, Sherry. Here, King checks Sherry Thill’s medicine to make sure she is doing OK, physically and emotionally. She spent about eight years homeless and has asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and severe depression.

‘Ready For Bad Luck To Happen’

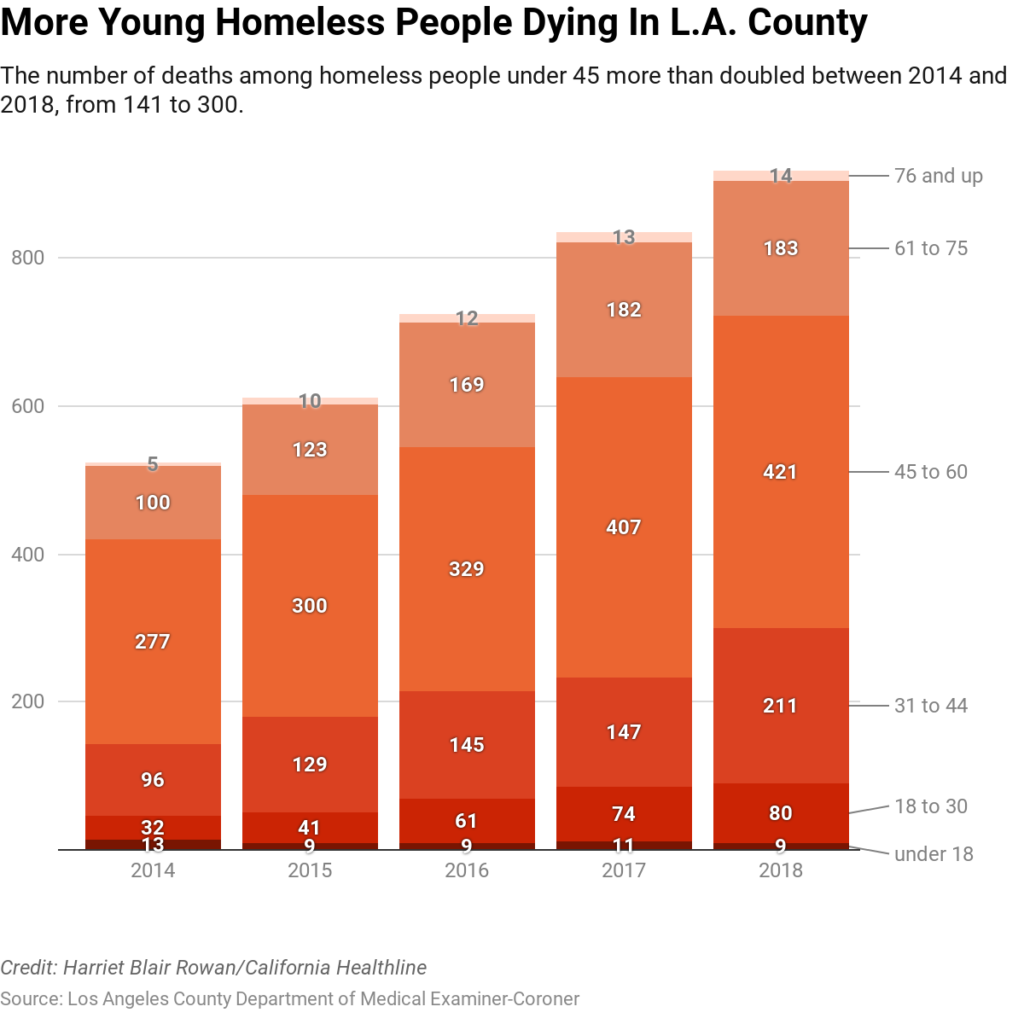

Homeless residents in Los Angeles also died from the same ailments as the general population — heart disease, cancer, lung disease, diabetes and infections. But they did so at a much younger age, said Dr. Paul Gregerson, who treats homeless residents as chief medical officer for JWCH Institute clinics in the Los Angeles area.

A stressful lifestyle, lack of healthy food and exposure to the weather contribute to an early death, he said. “If you are homeless, your body ages faster from living outside,” Gregerson said.

In Los Angeles County, the average age of death for homeless people was 48 for women and 51 for men. The life expectancy for women in California in 2016 was 83 and 79 for men — among the best longevity statistics in the nation.

Over the five-year period in L.A. County, there also was a sharp increase in deaths of younger adults who were homeless. For instance, the deaths of adults under 45 more than doubled.

The data does not include information about mental illnesses, which Elias of the coroner’s office said could be a contributing factor in some of the deaths.

Stephen Rosenstein, 59, was walking across the street in Panorama City, an L.A. neighborhood, when a car struck and killed him one night early last year, said his sister, Cindy Garcia. He had spent years bouncing from the streets to shelters to board-and-care homes, she said.

Rosenstein had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and manic depression, Garcia said, and often resisted help — behavior she attributed to his mental illness. “Most people would want to have a roof over your head,” she said. “He just fought it all the way.”

Rosenstein’s cause of death was listed as “traumatic injuries.” Deaths by trauma or violence were common among the homeless in the period analyzed: At least 800 people died from trauma, and of those, about 200 were shot or stabbed.

“They are ready for bad luck to happen,” King said.

Anna Gorman: agorman@kff.org, @AnnaGorman

Harriet Blair Rowan: hrowan@kff.org, @HattieRowan

Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit health newsroom whose stories appear in news outlets nationwide, is an editorially independent part of the Kaiser Family Foundation.