From UW Medicine

University of Washington Medicine has launched a number of initiatives to help patients and their friends and family cope with psychosis associated with schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia is a thought disorder, which causes you to think things and experience things differently from the rest of the world.

One of the defining criteria for schizophrenia is the presence of psychosis, a symptom of many mental disorders.

On May 14, the University of Washington School of Medicine will launch Psychosis REACH, the nation’s first program to teach evidence-based skills to help people whose relatives or friends have psychotic disorders.

Researchers worked with global experts to develop and implement the program.

The free, daylong training will be held on the UW campus in Seattle to teach people to better care for, and relate to, their loved ones.

Admission is free but advance registration is required; maximum attendance is 250.

A promising smartphone-based intervention for people with schizophrenia is being deployed at 20 health clinics across the state.

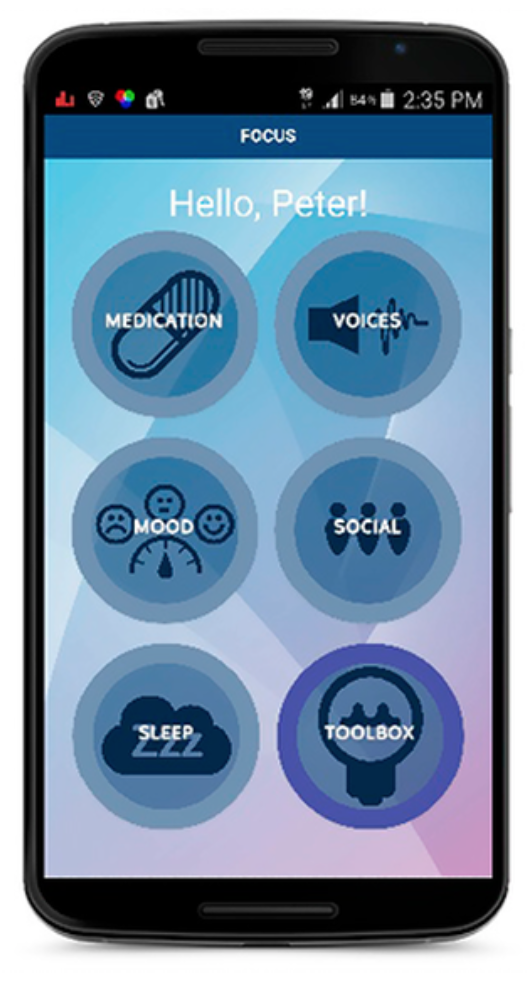

The FOCUS app, developed by clinicians and engineers at the University of Washington, acts as a pocket therapist: If a person is hearing voices or needs support, they can open the app and get help.

The project is funded by a $3.7 million award from the National Institute of Mental Health and is a collaboration between researchers at the UW, community clinics, policymakers, and people living with mental illness.

Last year, faculty members at the UW School of Medicine opened a First Episode Psychosis Clinic at Harborview Medical Center. The clinic provides teleconsulting and support to specialty care teams throughout the state.

“The nature of how we treat psychosis has evolved tremendously over the past 20 years, said Sarah Kopelovich, UW assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. She will be among the leaders of the training in May.

She said effective recovery involves mobilizing a clinical team and the affected person’s social and family network. That model, she said, should be standard practice within mental health systems.

“We want to provide patients well-researched strategies to help them cope with distressing symptoms and develop the life they want,” she said.

At least 100,000 young people are newly diagnosed with a psychotic disorder every year in the United States, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness. In Washington state, an estimated 19,000 people were diagnosed with psychosis disorders in 2013, the latest figures available.