Masoumeh Sara Rahmani, Coventry University

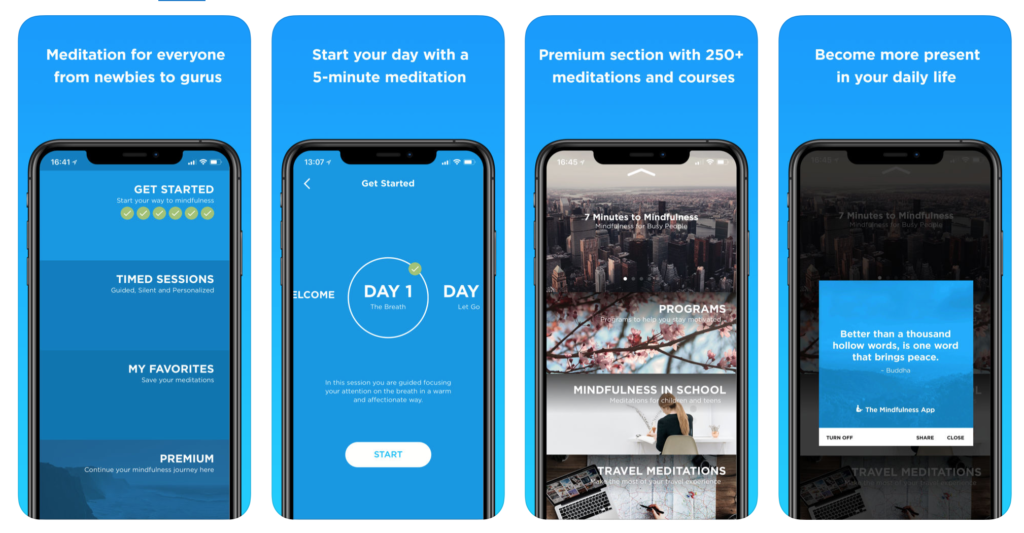

Mindfulness, it seems everybody’s doing it. You might have even tried it yourself – or have a regular practice. Thanks to the help of an app on your phone that speaks to you in dulcet tones, you are reminded to “let go” and to “observe your breath”.

From the public education to healthcare, the corporate world to the criminal justice system, parliament to the military, mindfulness is promoted as a cure all for modern ills.

Yet the evidence for the efficacy of mindfulness is not strong. In an article published in Perspectives on Psychological Science, a number of psychologists and cognitive scientists warn that despite the hype, scientific data on mindfulness is limited. They caution:

Misinformation and poor methodology associated with past studies of mindfulness may lead public consumers to be harmed, misled, and disappointed.

Studies on mindfulness are known for their numerous methodological and conceptual problems. This includes small sample sizes, lack of control groups, and insufficient use of valid measures.

To this list, the possibility of competing interests can also be added. In a recent example, the mega-journal PLOS ONE retracted a meta-analysis on mindfulness after concerns were raised over the methodology behind the results, including “double counting” and “incorrect effect estimates”.

The PLOS retraction also cited undeclared financial conflicts of interest by the authors. The journal noted that none of the authors agreed with the retraction.

Despite these issues, mindfulness has never been more popular and its influence in mainstream culture is massive, as can be seen in the creation of a new professorship in mindfulness and psychological science at the University of Oxford.

The position was created by the Oxford Mindfulness Centre, which became affiliated with the university’s Department of Psychiatry in 2011, after initially establishing as a private company in 2007 and later registering as a charity. It has since become a key player in shaping both the academic studies of mindfulness and the public’s perception of the practice.

A brief history of mindfulness

Mindfulness is a type of meditation derived from the Buddhist tradition. It encourages the observation of present thoughts, emotions and bodily sensations in a non-judgemental way. But how did it gain such prominence in Western mainstream culture?

For a start, the modern concept of Buddhism that Westerners relate to today did not exist a century ago. This new style of Buddhism is known as “Buddhist Modernism”, or “Protestant Buddhism” – a reform movement of the late 19th century.

This form of Buddhism was developed as a result of the influence of Christian missionaries and to the colonialism and imperialism of South-East Asia by European nations. To respond to their colonial situation, the elite of the movement reshaped Buddhism by aligning it to Western science and philosophy. This was done by representing Buddhism as rational, universal and compatible with science – with an emphasis placed upon meditation and personal reflection.

The advocates of this reform projected modern Western values onto Buddhist teachings who claimed to teach the “pure” Buddhism as taught by the historical Buddha himself.

Contemporary meditation teachers, including Jon Kabat-Zinn (JKZ), the founder of Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction(MBSR) – an eight-week programme that offers mindfulness training to help people with stress and pain – inherited and popularised this version of Buddhism.

When pressed about the Buddhist elements of their courses, teachers such as JKZ argue the technique is not Buddhist, but the “essence” of the Buddha’s teachings. These are said to be “universal” and compatible with science. Or as JKZ has put it, “the Buddha himself was not a Buddhist”.

These associations with Buddhism allows advocates of mindfulness to relish the legitimacy associated with the historical Buddha – yet at the same time avoid any undesired “religious” connotations. Likewise, when mindfulness is declared as “universal” then it seems to be less about Buddhism and more about a “basic human ability”.

Read more: McMindfulness: Buddhism as sold to you by neoliberals

Science and mindfulness

The idea that mindfulness is secular because it is scientifically tested is a common strategy used by advocates of mindfulness to disassociate the practice from its religious foundation and to promote it in clinical and educational settings.

It is well documented that JKZ intentionally downplayed the Buddhist roots of mindfulness to introduce it in clinical settings. In JKZ’s own words, he “bent over backward to structure it [MBSR] and find ways to speak about it that avoided as much as possible the risk of it being seen as Buddhist”. In essence then he translated Buddhist ideas into scientific and secular language.

This approach takes advantage of the authority of science in modern Western cultures as well as the perceived opposition of “science” with “religion”. And by aligning mindfulness with science, its opposition to “religion” is implicitly conveyed.

Legitimatising mindfulness

Appealing to science and empirical studies are not the only methods that mindfulness leaders have used to lend explicit legitimacy to mindfulness. The flourish of MA and PhD programmes, specific journals, conferences, university affiliated research centres – and now the professorship – demonstrate the movement’s efforts to legitimise and secure the future of mindfulness as an academic enterprise.

But although mindfulness claims to offer a staggering collection of possible health benefits – and aligns itself with science and academia to be seen as credible – as yet there is remarkably little scientific evidence backing it up.

That’s not to say a lot of people don’t find it beneficial. Indeed, many people practice mindfulness everyday and feel it helps them in their lives. The problem is though that there is still a lot researchers do not know about mindfulness – and ultimately the field needs a much more systematic and rigorous approach to be able to support such claims.

Masoumeh Sara Rahmani, Research Associate in Anthropology of Religion, Coventry University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.