Graham Pruss, CC BY-NC-ND

Graham Pruss, University of Washington

My neighbor, Billy, has lived for 17 years in a 20-foot-long recreational vehicle parked within a mostly industrial, but now gentrifying, neighborhood in Seattle.

A 68-year-old former carpet layer and handyman, Billy says he wants to move out of his RV, but he doesn’t have the income, savings and credit or rental history to rent in Seattle’s expensive housing market.

The lack of off-street space for his vehicle and city parking restrictions offer few options for leaving his home unattended while he finds employment, housing or social service assistance.

I asked Billy once if he used services designed for the homeless. He paused, then answered, “I’m not homeless. This RV is my home.”

During the last decade, I have studied how people use vehicles for shelter in Seattle. I found that a growing number of Americans, like Billy, value these mobile shelters as a form of affordable housing.

Representation needs recognition

Since 2005, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development has asked communities throughout the U.S. to report the number of people who sleep in shelters, transitional housing or public spaces on odd-numbered years, as part of a national count of the homeless.

However, there is no official method for counting people who live in their vehicles. Some cities’ counters simply look for condensation on windshields early in the morning, while others suggest that “you’ll know it when you see it.”

With no way to distinguish “the homeless” from seniors and retired “snowbirds” who vacation in an RV, San Diego removed RV residents from their 2019 federally reported count of all people who sleep in public spaces.

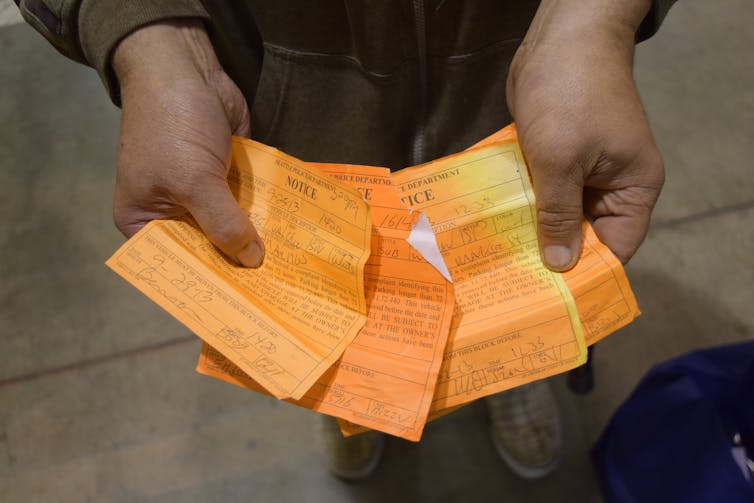

News reports from across America tell of vehicle residents from virtually every background attempting to settle in cities. They find themselves essentially blocked from local communities and social services, because there are few parking spaces to leave their home where it is safe from tickets or from being towed.

Without official recognition, there is little political representation to protect these communities from legal discrimination, such as signs that banish them from public spaces, as well as private property seizure.

As Billy once told me, “You can really feel the squeeze out here. There’s no way out.”

The science of settlement

In Seattle, during the last 25 years, an economic boom has driven up housing costs to unaffordable levels and, consequently, homelessness has increased.

The scale of vehicle residency in King County has nearly quadrupled in the last decade, from 881 to 3,372 people sleeping in a car, RV, school bus, truck or van. Vehicle residency was the most common form of shelter for people who lived in public space during this time, used by at least 30% of the local unsheltered community.

For two years, I worked for a nonprofit as the only street outreach specialist funded by the city of Seattle to connect approximately 1,500 local vehicle residents with social services. These individuals and families relied on vehicles to survive unaffordable housing markets, labor and industry shifts, and natural or personal disaster.

I have known hundreds of people who moved into vehicles in public parking lots as a way to stay connected to familiar neighborhoods. Some slept in an RV even while employed at well-paid, high-tech jobs to avoid paying punishingly high rents.

As my study progressed, I led teams of researchers to develop a method to count and map anonymous vehicle residences in public parking. We looked for at least three out of six basic characteristics of residency:

- The view through windows from front to back is blocked.

- The view through at least one side window is blocked.

- There is unfrozen condensation on the inside of windows.

- At least one window is partially open.

- Items that indicate residence are attached to the outside of the vehicle – such as generators, bicycles or storage containers.

- A large volume of items are stored in plastic bags inside or next to the vehicle.

Seattle and King County adopted this identification process for its annual estimated census of the homeless in 2017 and 2019.

Our standardized method enables volunteers to document a vehicle used for primary residence without disturbing occupants during the early morning counts, improving the accuracy and confidence of vehicle counts. These annual counts are followed by surveys that determine the average number of occupants per vehicle.

By 2018, with the help of our improved counting methods, we found that at least 53% of people who slept outside throughout King County were in a vehicle.

These reports are vital to develop appropriate funding for services to assist all unsettled, unhoused and homeless neighbors. Without an accurate count, cities around the U.S. are unable to appreciate how many vehicle residents they have – or what sort of services they may need.

Turning RVs into private shelters

In my view, recognizing local vehicle residency is the first step to representing these communities in social services. The next step is to provide a safe space off public streets for vehicle residents who need to connect with these systems of care.

Many cities have forced vehicle residents to move around within or between communities and out of public spaces. This approach increases law enforcement and social service outreach costs, while further destabilizing vulnerable and isolated neighbors.

Like many American cities, Seattle offers few off-street parking spaces connected with social services. Assistance typically funnels through brick-and-mortar shelters, which often lack parking space for vehicle residents.

The lack of legal off-street space for urban vehicle residency means that most vehicle residents have no option but to survive in public parking, where they suffer through parking tickets, property seizure and instability.

While many communities across the U.S. struggle to develop brick-and-mortar shelters, vehicle residences are privately owned and occupied throughout American streets now. I believe that cities need to do more to assess the true number of local vehicle residents, to provide them with a place to park and access vital social services.

Without professional assistance, vehicle residents have no option besides public parking to survive. Billy, and thousands like him, could use a home for their homes.

Graham Pruss, Ph.D. in Anthropology, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.