Research Check: have scientists found the cause of endometriosis?

Mathew Leonardi, University of Sydney; George Condous, University of Sydney, and Mike Armour, Western Sydney University

Headlines over the past week have given false hope to the roughly 8–10% of women of reproductive age with endometriosis:

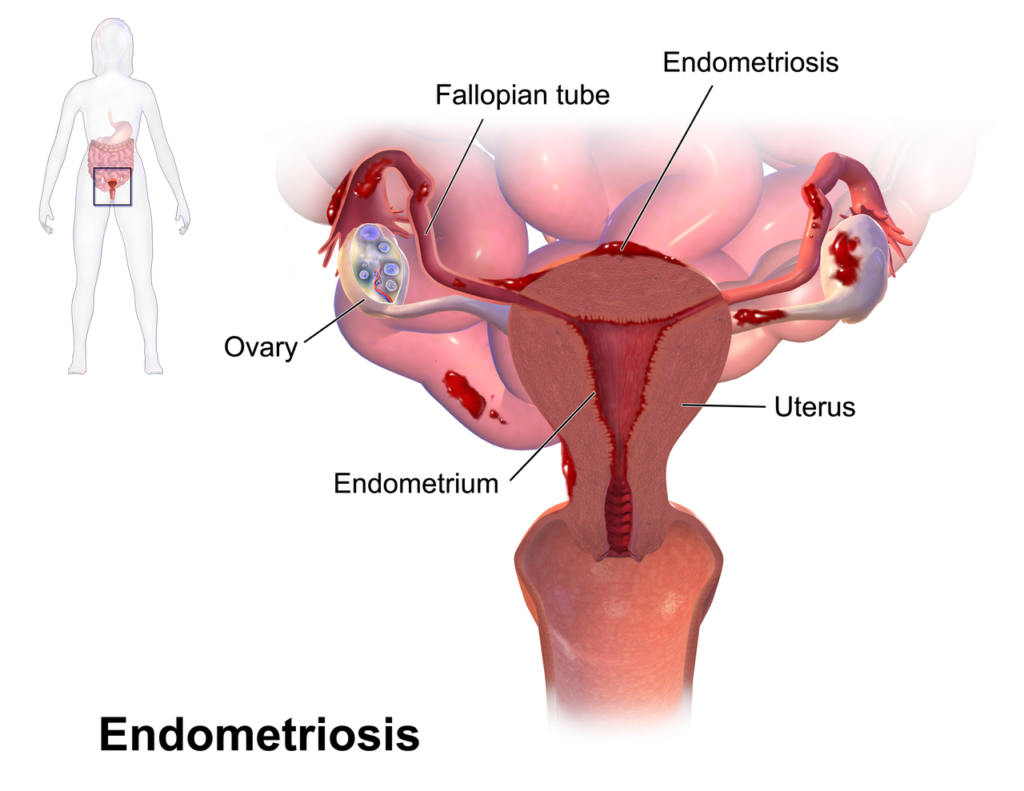

Endometriosis is an inflammatory disease where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus (called the endometrium) is found outside the uterus, causing pelvic pain and/or infertility.

We don’t know what causes endometriosis and, while surgery and medical management can help many women manage their symptoms, the condition negatively impacts women’s lives in almost every area, from work to intimate relationships.

Read more: Considering surgery for endometriosis? Here’s what you need to know

The new paper comes from a UK team studying the mechanisms behind pain in endometriosis, mostly in mice artificially induced to have endometriosis.

They found mice with endometriosis had higher levels of a type of white blood cell (called a macrophage) than healthy mice. This led to increased production of a growth hormone known as insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1.

When the levels of macrophages and IGF-1 were lowered, the mice behaved in ways that implied they had less pain.

While this was a very well-designed study and these insights might help us get closer to understanding why the pain in endometriosis seems to persist despite medical or surgical treatment, the researchers haven’t found the cause of the disease, let alone a cure.

How was the research conducted?

There were three main parts to the study: one in live mice, one looking at how mice cells responded in a lab environment, and a component that focused on human women.

Mice experiments

The researchers performed two experiments on two groups of mice: one group had endometriosis, the other didn’t.

The first experiments compared levels of macrophages – a specific type of white blood cell involved in the immune system – in mice with and without endometriosis, then monitored mice behaviours that reflect pain.

The researchers then attempted to reduce the level of macrophages and IGF-1 release in some of the mice with endometriosis. They wanted to assess whether pain levels would be reduced or return to the same levels as the mice without endometriosis.

The second experiment identified that the hormone IGF-1, produced by macrophages, is higher in mice with endometrosis.

The researchers exposed half of the mice with endometriosis to a drug that would block IGF-1 and again assessed their pain-related behaviour.

Lab studies of mice cells

Another two aspects of the study took place in mice cells.

One looked at the changes in markers of inflammation in the brain and spine of mice with and without endometriosis.

The second looked at nerve growth and sensitivity to pain in the presence of IGF-1.

Testing the theory in women

The researchers attempted to demonstrate that IGF-1 was higher in endometriosis tissue and the peritoneal (abdominal cavity) fluid of women with endometriosis compared to women without.

To do this, they recruited women with chronic pelvic pain who were undergoing laparoscopy (a procedure where a camera and surgical tools are used via small cuts in the abdomen) for diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis.

What were the results?

The researchers found mice with endometriosis had higher concentrations of macrophages than those without endometriosis. These macrophages had increased production of IGF-1.

In women with endometriosis, the researchers detected macrophages that produced IGF-1 within endometriosis tissue specifically.

Women with endometriosis also had a greater concentration of IGF-1 in their peritoneal (abdominal cavity) fluid than women without endometriosis. Their pain scores increased as their IGF-1 levels increased.

When the researchers tried to reduce the concentration of macrophages in mice, the animals seemed to exhibit fewer pain-related behaviours. But not all behaviours changed with the reduction of macrophages.

Similarly, when mice were given a drug that prevented IGF-1 from having its normal effect, mice seemed to experience less pain.

The effect of reducing macrophages in mice also seemed to have a positive effect on reducing inflammatory markers at the level of the brain and spine.

What does it all mean?

The researchers found evidence that IGF-1 was higher in both women and mice with endometriosis, and this rise was due to increased production by macrophages, which are associated with endometriosis.

These increased levels of IGF-1 seem to contribute to the pain experienced by mice with endometriosis. This is likely to occur because IGF-1 encourages nerve development, which makes that tissue more sensitive to pain.

It’s important to remember that mice are not just small, furry humans, so we need further studies to determine if these high levels of IGF-1 have the same contribution to pain in humans as in mice, and if reducing them has the same effect on pain that was observed in the mice experiments.

We also need to keep in mind that these mice had endometriosis for a relatively short time compared to the many years that women with endometriosis have the disease. There may be other changes occurring over the longer term that can’t be explored in these mice models.

The study gets us one step closer to understanding why endometriosis causes pain and offers a cautiously optimistic hope for future therapies to treat women experiencing endometriosis-related pain.

But it does not explain the cause (or causes) of endometriosis, which remains evasive.

Mathew Leonardi, Mike Armour and George Condous. Cecilia Ng, Clinical Trials Network Manager of the National Endometriosis Clinical and Scientific Trials (NECST) at Jean Hailes for Women’s Health, also contributed to this article.

Blind peer review

This Research Check is a good summary and interpretation of the research paper on the association between IGF-1-related pain and endometriosis.

This study is published by a respected research team and they are careful not to overstate their findings. By contrast, the newspaper article in The Sun is a major misrepresentation of the study and one that would unnecessarily raise hope of an imminent cure for endometriosis in the minds of the many women suffering from this disease.

Endometriosis is a complex disorder that has both genetic and environmental risk factors. It is unlikely that any single issue will be found that is solely responsible. This is reflected in the several different approaches to treatment that are currently in use. – Peter Rogers

Research Checks interrogate newly published studies and how they’re reported in the media. The analysis is undertaken by one or more academics not involved with the study, and reviewed by another, to make sure it’s accurate.

Mathew Leonardi, Gynaecologist and PhD candidate, Nepean Clinical School, University of Sydney; George Condous, Associate Professor, Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Neonatology, Nepean Clinical School, University of Sydney, and Mike Armour, Post-doctoral research fellow, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.