Yulia Grigoryeva/Shutterstock

Melissa Kang, University of Technology Sydney

Around one-quarter of the world’s population menstruate. That’s more than 1.9 billion people in the world who will bleed, on average, for 65 days a year.

The reusable menstrual cup and disposable tampon were both developed in the 1930s. But due to the tampon’s greater commercial potential, tampons were aggressively marketed, which is thought to be the reason behind their much greater uptake.

Growing concern about the environmental impact of disposable tampons and sanitary pads, as well as the need to offer more options for menstrual management in low- and middle-income countries, has led to a resurgence of menstrual cups.

A recent Lancet Public Health study found menstrual cups were a safe and effective alternative to manage periods.

Read more: Cups, lingerie and home-made pads: what are the reusable options for managing your period?

What is a menstrual cup?

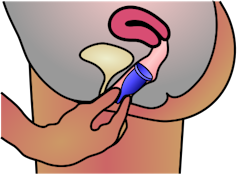

The menstrual cup is a reusable device for collecting menstrual fluid. Most are bell-shaped and designed to sit low in the vagina.

Some cups are designed to sit up against the cervix, and have a flatter, disc shape.

The most comparable menstrual product is the tampon, as it also inserts into the vagina. The main differences in use between the two are:

- tampons are disposable (although reusable ones are available); menstrual cups are not (although disposable versions exist)

- tampons absorb menstrual fluid whereas menstrual cups collect it

- tampons hold about half the volume of menstrual fluid compared with cups, and therefore need to be changed more frequently.

Menstrual cups are made from medical-grade silicone, latex rubber or elastomer, and can hold 10–38ml of fluid.

Depending on the heaviness of menstrual flow and the cup itself, menstrual cups need to be emptied every 4-12 hours.

One cup can be used for up to ten years.

Similar levels of leakage

The Lancet study’s authors conducted an extensive search of academic and “grey” literature (documents published by various organisations such as government and industry and in a range of formats besides academic journals), as well as websites with information about cost and availability of menstrual cups.

The researchers found 199 brands of menstrual cup, with availability in 99 countries.

They analysed the findings from 43 research studies involving a total of 3,319 people. The studies varied in purpose, design and quality.

Four studies made direct comparisons in leakage between the menstrual cup and tampons or pads, and found that it was similar or lower for cups.

Safety issues and side effects

There was no increase in infection rate among menstrual cup users compared with other products in a range of studies across several countries.

Toxic shock syndrome, once associated with super-absorbent tampon use, was reported in five people, though only one of these was confirmed (where the cup had been in place for 18 hours).

One trial compared toxic shock syndrome between menstrual cup and pad use among several hundred schoolgirls in rural Kenya, and found zero cases of toxic shock syndrome in either group.

Read more: Toxic shock syndrome is rare. Be vigilant but not alarmed

Other studies found either no, or reduced, association of cup use with infections such as bacterial vaginosis and candidiasis (thrush).

One study reported on seven cases of IUD (intrauterine device) dislodgement during removal of the menstrual cup, which appeared to be related to the length of the IUD string and the pressure exerted when pulling the cup out.

This highlights the importance of releasing the vacuum seal of the cup before removing it. This can be done by placing a finger up the side of the cup towards its rim and squeezing gently. The cup can then be pulled out at an angle.

Other safety issues identified included difficulty removing the cup, vaginal or pelvic pain, vaginal irritation, and allergic reaction to silicone.

It takes time to get used to cups

Studies exploring the acceptability of menstrual cups among users found issues such as discomfort or pain with insertion or removal.

Overall, 11% discontinued use, while 73% of participants across 15 studies with relevant data wanted to continue to use it.

In addition, the review authors found that awareness of menstrual cups was low, and that information about cups was lacking on educational websites.

So it’s important that women and girls who are thinking about using the menstrual cup have access to good information and peer support while they familiarise themselves with how the menstrual cup works and feels. An adolescent anticipating their first period also deserves to know all the options available to them.

The review authors listed several websites dedicated to the menstrual cup, and while not endorsed by them, suggest Put a Cup In It FAQ and Cleveland Clinic as useful resources. CHOICE also compiled a useful product guide for Australian consumers earlier this year.

Read more: Period pain is impacting women at school, uni and work. Let’s be open about it

Melissa Kang, Associate professor, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.