Opioids study shows high-risk counties across the country, suggests local solutions to epidemic

From Institute for Healthcare Policy & Innovation at the University of Michigan

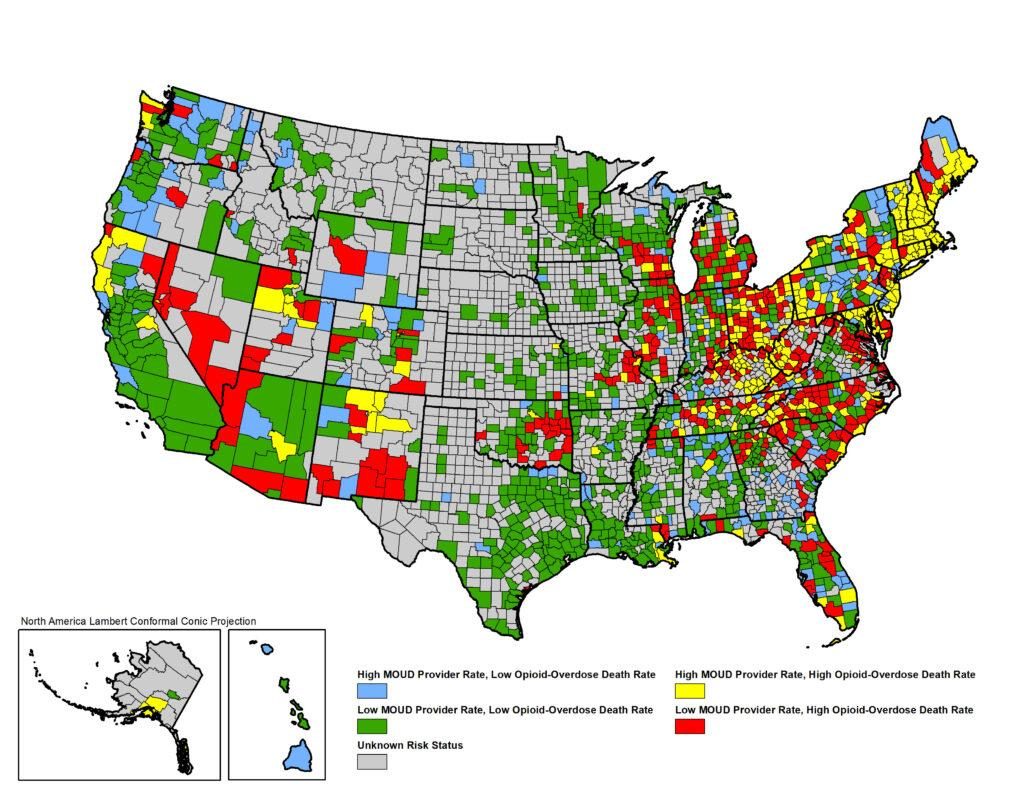

Dozens of counties in the Midwest and South are at the highest risk for opioid deaths in the United States, say University of Michigan researchers.

In a study of more than 3,000 counties across the U.S., the researchers found that residents of 412 counties are at least twice as likely to be at high risk for opioid overdose deaths and to lack providers who can deliver medications to treat opioid use disorder.

States with among the most high-risk counties include: North Carolina, Ohio, Virginia, Kentucky, Michigan, Tennessee, Illinois, Indiana, Georgia, Oklahoma, West Virginia, South Carolina, Wisconsin and Florida.

The study, published in the June 28 issue of JAMA Network Open, suggests strategies for increasing treatment for opioid addiction, including by increasing the number of primary care clinicians capable of providing medications as well as improving employment opportunities in those communities.

“We hope policymakers can use this information to funnel additional money and resources to specific counties within their states,” said lead author Rebecca Haffajee, assistant professor of health management and policy at the U-M School of Public Health. “We need more strategies to augment and increase the primary care provider workforce in those high-risk counties, people who are willing and able to provide opioid use disorder treatments.”

The U-M researchers looked at opioid overdose mortality rates in 3,142 U.S. counties between January 2015 and December 2017. They defined an opioid high-risk county as one with opioid overdose mortality above the national rate and with the availability of providers to deliver opioid use disorder medications below the national rate.

The study, they say, is the first to include data from all three opioid use disorder medications on the market, including methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone.

Their analysis included publicly listed providers of methadone (1,517 opioid treatment programs), buprenorphine (24,851 clinicians approved to prescribe the medication) and the extended-release naltrexone product Vivitrol (5,222 health care providers, as compiled by the drug manufacturer).

In their cross-sectional study, the researchers also looked at demographics, workforce, access to health care insurance, road density, urbanicity and opioid prescriptions.

Among counties analyzed, they found that:

- 412 counties (13%) are classified as high-risk, having both high opioid overdose mortality and low treatment capacity.

- 751 counties (24%) had a high rate of opioid overdose mortality.

- 1,457 (46%) counties lacked a publicly available provider of opioid use disorder medication.

- 946 out of 1,328 rural counties (71%) lacked a publicly available provider of opioid use disorder medication.

The study found that certain factors—such as a younger population, lower rates of unemployment and higher density of primary care physicians—are associated with a lower risk of opioid overdose death and lack of capacity to treat opioid use disorder.

Haffajee, also a member of the U-M Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, said it’s important to understand the differences of the opioid epidemic at the local level.

“In rural areas, the opioid crisis is often still a prescription opioid issue. But in metropolitan counties, highly potent illicit fentanyl and other synthetic opioids are more prevalent and are killing people,” she said. “That’s likely why we identified metropolitan areas as higher-risk, despite the fact that these counties typically have some (just not enough) treatment providers.

“Understanding these differences at the sub-state level and coming up with strategies that target specific county needs can allow us to more efficiently channel the limited amount of resources we have to combat this crisis.”

In addition to Haffajee, authors included Lewei Allison Lin, assistant professor of psychiatry; Amy Bohnert, associate professor of psychiatry; and Jason Goldstick, research assistant professor of emergency medicine. All are part of the Opioid Solutions Network at U-M.