The Pew Charitable Trusts

By Max Blau, Stateline

MONTGOMERY, Ala. — When his HIV specialist left Selma, Larry wondered where he would get care next. He already drove an hour from his small Alabama town to the city where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. once marched to the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Would he have to drive even farther — perhaps double the distance to Montgomery — to get his semi-annual checkups?

But Larry caught a break. He could still drive to Selma, he was told, on one condition: He would have to videoconference with his new doctor.

So, on a recent visit, after a nurse checked his vitals, he spoke with Dr. Laurie Dill, an HIV physician who was based 50 miles east in Montgomery. Dill could listen to Larry’s heart and lungs through Bluetooth headphones equipment. The two could discuss his lab results and any potential concerns he faced.

“I’m able to have the same conversations with my doctor — except now it’s over a television screen,” said Larry, who spoke to Stateline on the condition his name was not published, citing the stigma that still exists with HIV. “Nothing else changed.”

The Trump administration is pushing to cut new HIV transmissions 90% nationwide by 2030, focusing its efforts on 48 urban counties and seven states, including Alabama, with disproportionately high rates of HIV occurrence. But in the South, which has more hotspots than any other region, HIV treatment providers describe an overwhelming load of patients because of the lack of new colleagues entering the field.

The nonprofit where Dill works, Medical Advocacy and Outreach, now conducts nearly 5,000 patient visits a year, in large part thanks to telemedicine. It’s more efficient than the hours she spent 20 years ago driving around the state to see patients, but it’s still not enough for the region’s growing patient load.

With nearly 40,000 new HIV cases each year nationally — and potentially thousands more still undiagnosed — current providers worry their workforce is so understaffed that it will be hamstrung in making the treatment of HIV similar to that of other chronic diseases.

Even though Medical Advocacy and Outreach was recently praised during a visit by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Dr. Robert Redfield as a top example of rural HIV care, Dill says what her organization lacks most — a larger workforce — is what limits the clinics’ ability to serve even more people like Larry.

“To end the epidemic, we need to double our capacity to treat HIV patients,” she said.

Federal health officials involved with the “End the Epidemic” effort are largely focused on providing more resources to help in four areas: diagnose patients unaware of their HIV status, treat people who test positive, prevent new transmissions and respond to potent outbreaks of the disease.

One study from policy research organization Mathematica found that HIV providers have already declined 5% nationwide, even though demand increased by 14% from 2010 to 2015. And a 2016 report from the Southeast AIDS Education and Training Center, an eight-state consortium that offers educational resources to HIV treatment providers, warned the retirement of older practitioners, combined with fewer entering the specialty, has made it difficult to recruit and retain practitioners.

“It’s a real problem that keeps me up at night,” said Dr. Anna Person, an infectious disease doctor with Vanderbilt University Medical Center. “As our patients do better, they are living longer and require more care. It’s a dumpster fire, a hotbed of the epidemic, in the South. We’re going to need more providers than ever.”

CDC data shows the South, which the agency defines as a 16-state region, saw more new cases — 19,968 — than the rest of the nation combined in 2017.

Georgia, Florida and Louisiana had the highest rates of new HIV diagnoses of any state. Texas, South Carolina, Mississippi and Alabama also rank among the states with the 10 highest rates of new HIV diagnoses.

In many of those states, gay black men face higher risks of contracting HIV — in part because of the lack of housing, transportation and money, which can affect one’s ability to stay connected to consistent preventive care — as do some women and people who inject drugs.

“A lot of people may not be able to afford to drive an hour or more to see a doctor,” said Larry, noting the limited public transportation options in Alabama. “When you have the opportunity to see a doctor that’s close, even if it’s not in person, it’s a huge benefit.”

Several providers interviewed by Stateline said cities, counties and states must spend more to expand HIV treatment access. While the federal government has traditionally funded care for patients living with HIV or AIDS — largely through the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program — providers say local officials must help create more training opportunities for future infectious disease specialists and incentivize current general practitioners to work with these patients.

Beyond that, experts also say local officials in areas deemed hotspots should devote more funding for data collection, screenings and programs to access pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for those at risk of contracting the disease. While states provide nearly one-third of dollars for HIV prevention nationwide, some Southern states have scaled back their funding or opposed Medicaid expansion, according to health officials, experts and providers.

“There is no such thing as ending the HIV epidemic — for all epidemics are local,” said Dr. Melanie Thompson, founder of the AIDS Research Consortium of Atlanta, a metro area that has four counties that are considered hotspots. “We’re not San Francisco. We’re not New York. We lack the political will to make the changes we need.”

Shortage of Specialists

Vanderbilt’s Person thinks few careers are more rewarding than being an HIV physician. But as the head of Vanderbilt’s infectious diseases fellowship program, where doctors who have completed residency receive two more years of specialty training, she said it’s hard to persuade trainees to join programs like hers.

Many Southern teaching hospitals struggle to fill fellowship slots, often because trainees saddled with medical school debt are wary of becoming infectious disease doctors, who are among the lowest-paid specialists in medicine. One-third of fellowship slots at Southern teaching hospitals went unfilled during the match process this year, according to a Stateline analysis of National Resident Matching Program data.

This upcoming year, New York will have twice as many infectious disease fellows than the five Deep South states — Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina — combined. (Some schools later find trainees who didn’t match to fill those spots, but the lack of interest indicates residents are reluctant to enter the specialty, HIV doctors say.)

Dr. Wendy Armstrong, medical director of Grady Health’s Ponce de Leon Center’s infectious disease program in Atlanta, said medical schools and internal medicine residencies don’t incorporate enough HIV care into their curriculum. Few students consider HIV care because it’s an underfunded field that operates on a “shoestring” budget, she said. Some even see the HIV epidemic as less urgent today compared with the 1980s.

The lack of resources for HIV trainees is reflective of the broader trend of inequitable funding for medical education. A 2013 study by George Washington University found that 29 states — including many in the South — received less than 1% of Medicare’s $10 billion for graduate medical education. Experts told Stateline that Southern states, which also fund medical education, should prioritize these programs.

Thompson also said states can mandate training for all doctors in HIV care — similar to opioid disorder treatment, for example — as a condition of licensure. Person thinks Southern states should offer loan forgiveness programs to prospective providers.

“When I was a young nurse, when someone was diagnosed with diabetes, they had to see a specialist,” said Christine Brennan, project director for LSU Health Science Center’s AIDS Education and Training Center. “Hopefully, we can move HIV to where it’s similar to diabetes. Treatment is safe, easy, one pill a day with minimal side effects.”

Expanding the HIV Treatment Workforce

Dr. Jay Butler, deputy director for infectious diseases at the CDC, said primary care providers and mid-level providers are essential to addressing the provider shortage in regions like rural Alabama. For that to happen, though, he said older primary care doctors must overcome long-held stigma toward patients with HIV, while newer doctors must receive additional training to “feel like they have the technical expertise to be able to manage HIV.”

“It’s hard to train old doctors,” says Dr. J. Dan Moore, an HIV specialist in Arkansas, where some patients will drive more than two hours for care. “We’re hoping new doctors can be comfortable.”

Dr. Michael Kolber, director of the University of Miami-Florida’s comprehensive AIDS program, thinks many primary care physicians choose not to work with patients with HIV because reimbursement outside of federally funded facilities happens on a fee-for-service basis. Primary care physicians often make money by churning through a high volume of patients.

“I came from primary care where, if I saw 20 patients in a day, I lost money,” said Dr. Marguerite Barber-Owens, a longtime private practice internist who switched over to working with HIV patients at Medical Advocacy and Outreach, which receives funding through the Ryan White program. “We’re doing HIV and primary care now, so I have less patients per day, but the extra time is necessary because of the complexity of the patients.”

In lieu of more doctors, Kolber thinks more mid-level providers, including nurse practitioners, should be able to treat HIV patients.

“When I train people, there’s rapid turnover because these are high-burnout positions,” said Armstrong, who trains providers at Grady’s Ponce de Leon Center. “We’re asking people to be social workers and all kinds of things in the middle of their half-hour appointment. I’m constantly training people to become skilled at something it takes a long time to be skilled at.”

In Florida, one of the Southern states leading the fight against HIV, health officials wrote in the state’s integrated HIV prevention and care plan that it “faces a serious crisis in care capacity as these clinicians retire without qualified recruits to take their place.”

And the Mississippi state health department’s 2017-2021 statement of need reported a “severe shortage” of physicians had led to a lack of full-time HIV clinics everywhere statewide except for Jackson.

Louisiana health officials said in the state’s HIV/AIDS Strategy report they must help those who are a part of the state’s HIV prevention workforce to get better at “understanding and addressing institutionalized racism, homophobia and transphobia, and trauma-informed care.”

Brennan said Louisiana should use data to drive workforce improvements. Some states collect data about both positive and negative HIV tests to see which providers are screening patients. But it wasn’t until this summer that Louisiana finally did the same, Brennan said. That key data point can help identify which swaths of the state are lacking providers and help health officials further allocate training resources to those areas.

“Parish health units and the state can see who’s not screening — and address providers [who are] not trained,” Brennan said. “We’ll never get HIV under control until we fix that the lack of screenings.”

Catching Up On PrEP

More than one million Americans are at high risk of HIV infection. But fewer than 10% of Americans at high risk of HIV take pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a drug that prevents people who are negative but at risk of HIV from contracting the disease.

But Dr. Mehri McKellar, an infectious disease doctor who works with an HIV clinic at Duke University, said the region’s primary care physicians and mid-level providers are “behind the eight-ball” in PrEP prescriptions compared with San Francisco and New York. According to the interactive online mapping tool AIDSVu, Southerners accounted for only 30% of PrEP users in 2016, even though the region was home to more than half of new HIV cases.

Ryan White funding, however, only covers patients diagnosed with HIV. While some HIV policy experts say the federal program should be tweaked to allow for PrEP funding, other providers say that responsibility now falls to state and local health departments.

And if general practitioners aren’t screening patients, they likely aren’t prescribing PrEP to the people who need it most, according to Thompson. And while PrEP is readily available and covered by private insurance and Medicaid, the price of the drug has dramatically increased in recent years.

But Gilead, which makes the leading brand, Truvada, has pledged to provide free PrEP to 200,000 people through 2030. “We’re just chipping away at [the need],” said Tom Andrews, president of Mercy Care, an Atlanta-based provider of HIV services.

But change could be coming to Georgia, where a bipartisan group of state lawmakers passed a bill to establish a three-year state pilot project to offer PrEP in areas that the CDC says are at risk of HIV outbreaks because of opioid use. Atlanta, too, has set aside $100,000 to support Fulton County in expanding PrEP services. Even still, Thompson said a pilot is insufficient, and that Georgia lawmakers should “treat HIV as the public health crisis that it is.”

“The places with the biggest epidemics, like Georgia, are not that way by accident,” Thompson said. “Part of the reason is the lack of political will to fund it.”

Back in Montgomery, Dill says Medical Advocacy and Outreach has figured out a way to offer PrEP to its uninsured patients — through profits generated from a partnership with the state’s STI 340(b) program and the use of Gilead’s patient assistance program — but she’s only reaching a fraction of Alabamans who need preventive services. And that’s insufficient, she said. Doctors prescribed PrEP to nearly a quarter of New Yorkers at high risk for HIV, but only 7% of Alabamans at high risk for HIV, according to CDC data.

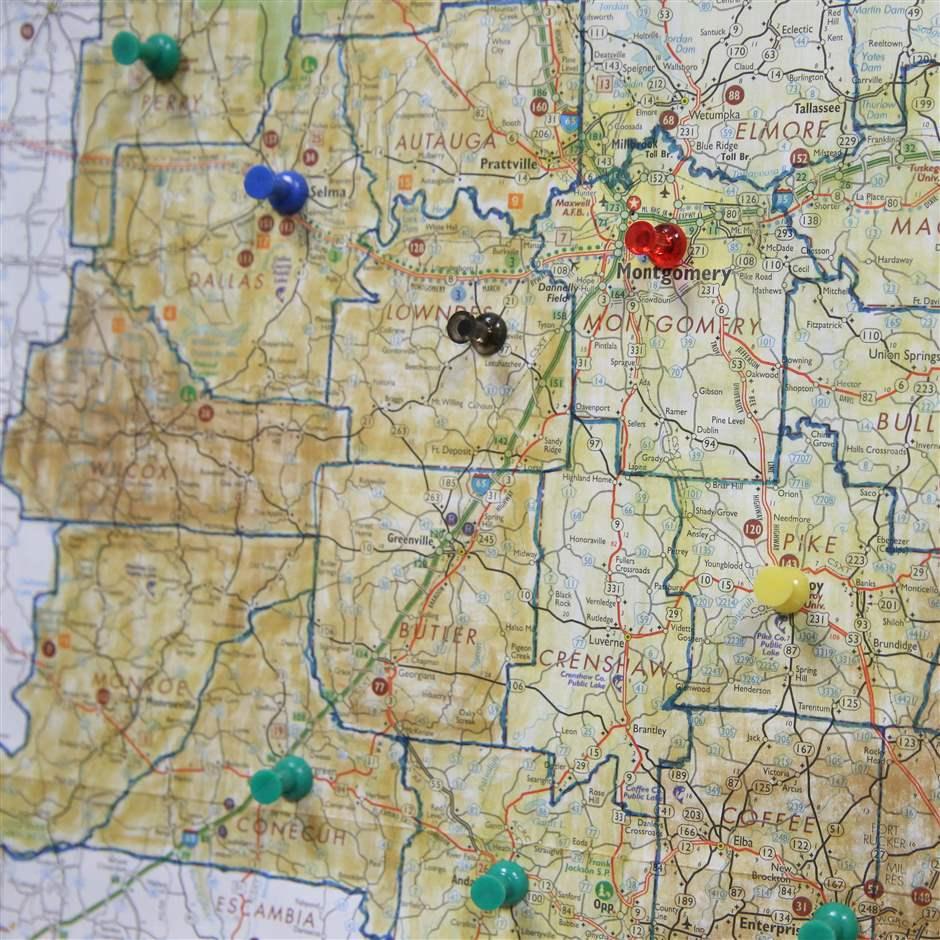

Down the hall from where Larry appeared on the flat screen, Dill points to a map of Alabama. From Montgomery to Dothan, she points out thumbtacks pinned into counties where Medical Advocacy and Outreach doctors and nurses have gotten hundreds of patients at risk of HIV to take PrEP. Then she looks at the rest of the counties, where PrEP prescriptions remain low. She says the reason is not a lack of patient interest, but a lack of providers trained on the importance of PrEP.

“A fourth of our patients are still coming in with an advanced stage of the disease,” Dill said. “Until that goes down, I don’t think we’re anywhere near getting a handle on this epidemic.”

Stateline is an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy. Since its founding in 1998, Stateline has maintained a commitment to the highest standards of non-partisanship, objectivity, and integrity. Its team of veteran journalists combines original reporting with a roundup of the latest news from sources around the country. Stateline focuses on four topics that are key to state policy: fiscal and economic issues, health care, demographics, and the business of government.