by Lena V. Groeger, Kaiser Health News

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

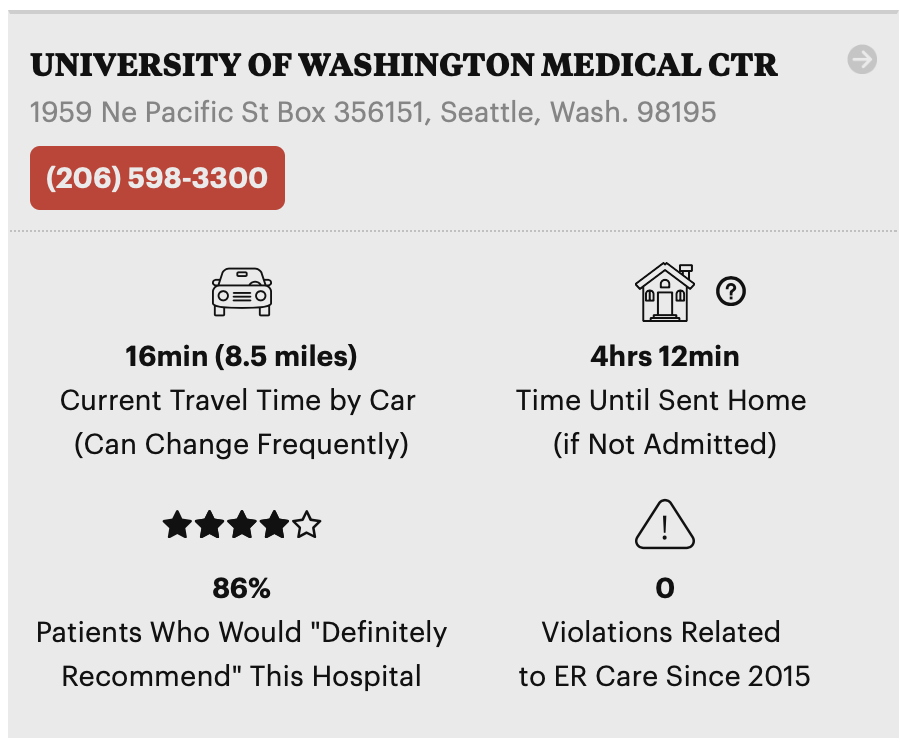

To be prepared in the event of an emergency, you can use our newly updated ER Inspector (formerly called ER Wait Watcher) to help you evaluate the emergency rooms near you.

Using data from the federal government, our interactive database lets you compare ERs on both efficiency measures, including how long patients typically spend in the ER before being sent home, and quality measures, such as how many violations related to ER care a hospital has had.

Note: If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or other life-threatening emergency, do not use ER Inspector. Call 911 and seek care immediately.

We’ve made a few substantial changes and upgrades to ER Inspector since it first came out in 2013. Notably, we’ve added hospital violations related to emergency room care since 2015. We’ve also removed two measures that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) no longer releases.

New: ER Violations Data

Hospitals in the U.S. that participate in Medicare are subject to health and safety regulations. They are inspected regularly every few years and also in response to complaints. CMS only publicly releases violations found during the investigation of a complaint — you can now see all of those emergency room violations since January 2015 in ER Inspector.

While CMS releases data on all types of hospital violations, or “deficiencies,” we pulled out the ones related to ER care. These include violations relating to not properly assessing and treating patients, inadequate medical and nursing staff and not following ER policies and procedures. It also includes violations of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), which requires ERs to provide a medical screening examination and provide treatment to stabilize anyone who comes to the emergency department, regardless of their ability to pay. ER Inspector now displays the percentage of hospitals in each state with at least one violation since January 2015, as well as a full explanation of each violation on each hospital page.

Still Here: What it Means to Have “Timely and Effective Care”

To demonstrate how well their emergency rooms provide “timely and effective care,” hospitals report a few key measures on a quarterly basis, all of which you can see in our database:

- Time Until Sent Home: The average time patients spent in the emergency room before being sent home if they weren’t admitted.

- Left Without Being Seen: The percentage of patients who left the emergency room without being seen by a doctor.

- Time Before Admission: The average time patients spent in the emergency room before being admitted to the hospital.

- Transfer Time: Among patients who were admitted, the additional time they spent waiting before being taken to their room.

- CT Scan: Percentage of patients who arrived with stroke symptoms and received brain scan results within 45 minutes. In ER Inspector we reverse this measure and display the percentage that did not receive a brain scan within 45 minutes.

While timing can vary depending on why someone came to the ER (a sprained ankle may take less time to treat than unexplained chest pain), long wait times are often signals of overcrowding or staff shortages.

Removed: Wait Time Before Seeing a Doctor

CMS removed two ER quality measures in April 2019.

The first was a measure of the average time patients spent in the ER before being seen by a doctor. In a 2018 rule, CMS outlined several concerns with the measure, including that it was not linked to improved patient outcomes, and that the wait times and reported time stamps were not always valid or accurate.

Ashish K. Jha, director of the Harvard Global Health Institute, agrees that the measure was not always accurate. According to Jha, hospitals sometimes indicate that they have seen a patient when in fact they haven’t actually examined them yet, in order to artificially shorten their reported wait times. “In concept it’s a good measure,” Jha said, “but much of the variation in wait time is due to gaming the measure.”

CMS also removed another measure on the average time patients with broken bones had to wait before receiving pain meds. In the same 2018 rule, CMS outlined concerns that the measure “may create undue pressure for hospital staff to prescribe more opioids.”