By Clark Merrefield, Journalists’ Resource

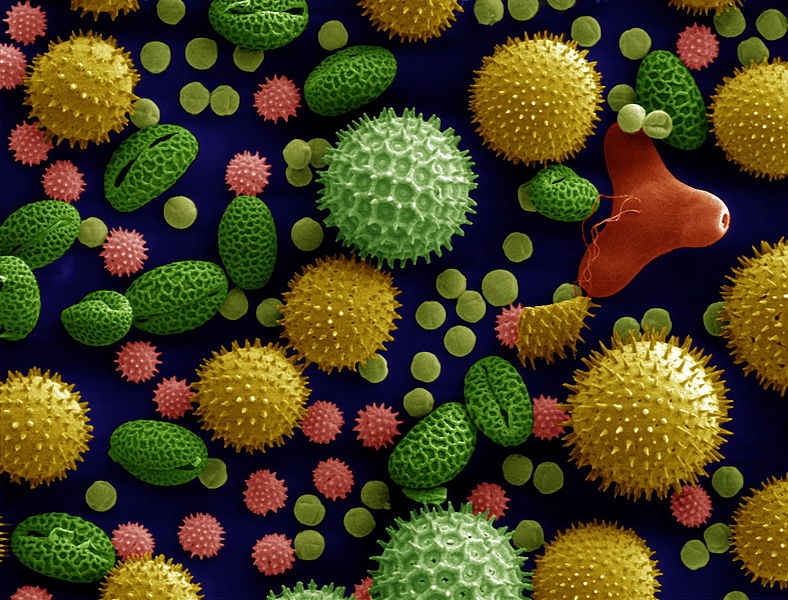

We’re just over the hump of peak ragweed season, when tens of millions of Americans suffer sneezing, itchy eyes and coughing brought on by pollen from plants like sage and mugwort. New research in the Journal of Health Economicsreveals something unexpected about allergies: U.S. cities experiencing unusually high pollen counts also experience lower rates of reported violent crime.

Looking at daily pollen counts across 16 U.S. cities from 2007 to 2016 and crimes reported to local law enforcement that the FBI collects, the authors find that reported violent crime falls 4% on high-pollen days. That drop is about the level of crime reduction that would come with a 10% increase in the size of a city’s police force, the authors write. The paper adds to past research investigating how health and other shocks — like football upsets — affect crime rates.

“Usually people look at effects of criminal justice policy, like incarceration rates and prison time,” says Monica Deza, assistant professor of economics at Hunter College and one of the paper’s authors. “Those are not the only approaches to fight crime. Not that increasing pollen or health shocks is a tool to fight crime, but it’s something to take into account.”

Past research has identified associations between violent crime and exposure to environmental toxins, like lead. Lead can change children’s brain structure, and childhood lead exposure has been associated with adult criminal behavior. Air pollution, which can also affect cognitive development in children, has also been linked to violent crime.

But pollen is not toxic to the degree that lead and air pollution are. And the reasons for the observed decrease in crime during high-pollen periods appear not to be neurological, but behavioral.

The authors focus on New York City to explore why more pollen might lead to less violent crime. Using detailed microdata they find the effect is largely due to reduced residential violent crime. Residential violent crime refers to violence that happens in the home — typically intimate partner and other domestic violence, according to the authors.

They turn to data from the bike-rental program Citibike as a proxy for outdoor activity. On high-pollen days — when pollen readings exceed 1,500 parts per million — Citibike activity declines 8%. That 1,500 ppm reading is the threshold for “high-pollen days” used throughout the paper. The average pollen count across cities during the period studied is about 172 ppm.

The authors write, “these results are consistent with the idea that individuals are more likely to remain in their homes on days in which pollen counts are high.” The behavioral change may be associated with run-of-the-mill allergy symptoms.

“Pollen makes people more fatigued, more tired,” Deza says. “The mechanism we are discussing in this paper is that if people are more fatigued and more lethargic, they may be less likely to be angry.”

High-pollen days don’t seem to lead criminals to simply put off their crimes until the air clears up. If people were committing more violent crime after pollen levels return to normal, that would mean pollen is merely making people put off criminal activity by a few days.

“But we show that the decrease in violent crime on high pollen days is not being offset by higher crime on low-pollen days,” Deza says.

Seasonal allergies can conversely be thought of as a shock to the cost of committing a violent crime, the authors write. Generally, crime rates go down when the cost of a crime goes up — for example, when there is a harsh potential legal punishment — and also when the benefits of committing a crime fall. Here’s a hypothetical the authors give:

“Consider, for example, an offender who commits assaults because of the rush that he feels in physically dominating another person. This offender may experience a reduction in the benefits of offending in the presence of an illness.”

The takeaway, Deza says, is not so much about what cities should or shouldn’t do on days when pollen is high, but rather what happens the rest of the time — particularly when environmental and other shocks lead to an uptick in violent crime. Past research has found, for example, that domestic violence rates increase 10% after professional football losses. Other research has found strong associations between violent crime and very hot weather.

“If people could manage their anger without being sick that would have positive effects on crime even on days when we don’t observe these health shocks,” Deza says.

The analysis included Atlanta; Austin, Texas; Baltimore; Bellevue, Nebraska; Colorado Springs, Colorado; Dayton, Ohio; Detroit; Greenville, South Carolina; Kansas City, Missouri; Knoxville, Tennessee; Louisville, Kentucky; New York; Rochester, New York; Seattle; St. Louis; and Twin Falls, Minnesota.

Citation: Aaron Chalfin, Shooshan Danagoulian and Monica Deza. “More Sneezing, Less Crime? Health Shocks and the Market for Offenses,” Journal of Health Economics, September 2019, doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2019.102230.

A project of Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center and the Carnegie-Knight Initiative, Journalist’s Resource curates, summarizes and contextualizes high-quality research on newsy public policy topics. We are supported by generous grants from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.