Fabien B. Vincent, Monash University and Michelle Leech, Monash University

Arthritis is a broad term to describe inflammation of the joints which become swollen and painful. There are many different kinds. Osteoarthritis, the most common, is caused by wear and tear.

This is followed by rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune condition where the person’s immune system mistakenly attacks and damages its own joints and other organs.

Rheumatoid arthritis is relatively common, affecting around one in 100 people, including young people and even children.

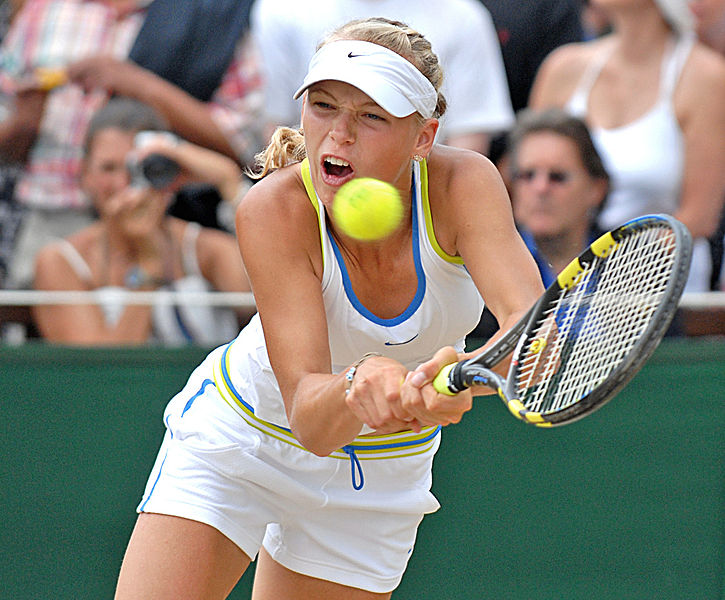

Twenty-nine-year-old Danish tennis player Caroline Wozniacki told fans last year she was diagnosed with this condition. Earlier in 2018, she had won the Australian Open, then struggled with unexplained symptoms.

Researchers do not fully know what causes rheumatoid arthritis, but suspect certain genes may trigger it when combined with environmental and lifestyle factors such as smoking or infections.

How does it feel?

People commonly experience joint pain, but it is particularly bad in the mornings and when they rest. Joints in the hands, feet, wrists, elbows, knees and ankles may be stiff for hours at a time. But unlike osteoarthritis, the pain can actually get better with movement.

If the inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis is not controlled, people experience joint pain, stiffness, fatigue and can almost feel like they have the flu.

The inflammation can lead to damage to the bones and cartilage (cushion) in joints causing deformity and disability. This can affect work, and social and family life.

In 18% to 41% of patients, the condition can cause inflammation in other parts of the body, such as the lungs (this may cause a condition called interstitial lung disease) and the blood vessels (leading to a condition called vasculitis).

People with severe rheumatoid arthritis also have an increased risk of developing lymphoma, a type of cancer of the lymphatic system, which helps rid the body of toxic waste.

How is it diagnosed?

When a GP suspects someone has rheumatoid arthritis, the patient is referred to a rheumatologist for a detailed physical examination focusing on joint pain, tenderness, swelling and stiffness.

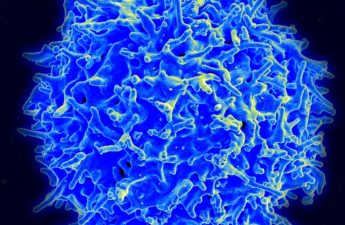

The patient will have some routine blood tests to look for signs of inflammation and “autoimmunity” – antibodies directed against the patient’s own tissues.

Read more: Explainer: what is the immune system?

The person may also have an x-ray of the affected joints (if the symptoms have been present for more than three months) to look for signs of cartilage thinning and bone erosion (small bites out of the bone).

Ultrasound and MRI are less useful for diagnosis, but can sometimes be used to monitor the condition.

How is it treated?

While there is no cure for rheumatoid arthritis, medicines can effectively control the condition and stop visible signs of damage.

With good treatment, it’s now very rare to see deformed joints or people in wheel chairs.

Treatments should start as early as possible and will vary according to how active and severe the condition is. Some people need only a small amount of medicine whereas others will try many different medicines, sometimes in combination.

Because the immune system is overactive and mistaken in its target, the treatment approach is to dampen the immune response.

Initial treatment may include a low dose of steroids called prednisolone, as well as an immune-suppressing drug such as methotrexate or leflunomide, to control the inflammation.

Read more: Weekly Dose: methotrexate, the anti-inflammatory drug that can kill if taken daily

If the condition is not controlled by these drugs, then other medicines, mostly injections, called “biological” drugs, can be added. These mimic substances naturally produced by the body and block specific substances in the immune system. Very recently, some newer tablets have been approved for rheumatoid arthritis.

Pain management may also be needed with medicines like non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen.

Inflamed, swollen joints can also periodically be treated by local joint injection of steroids.

People with rheumatoid arthritis will also greatly benefit from physiotherapy and occupational therapy. They will learn exercises to maintain joint flexibility, as well as alternative ways to perform daily tasks that may be difficult or painful.

But the fatigue is very difficult to treat. Gentle graduated exercise programs, a good healthy diet, understanding of the condition and its treatment, as well as psychological support, can help with fatigue.

Most people with rheumatoid arthritis can no longer be distinguished from people without the condition and live full and active lives. However, for a small percentage of unlucky patients who have aggressive disease or cannot tolerate any of the medicines, the course can be more difficult.

Read more: Explainer: what is Sjögren’s syndrome, the condition Venus Williams lives with?

Fabien B. Vincent, Research Fellow; Rheumatology Research Group, Centre for Inflammatory Diseases, Monash University and Michelle Leech, Rheumatologist, Professor/Director Monash Medical Course/ Deputy Dean Health Faculty, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.