Cornelius (Neil) J. Clancy, University of Pittsburgh

In 2013 I took care of a gentleman who underwent surgery for what all his physicians, including me, thought was liver cancer. Surgery revealed that the disease was a rare but benign tumor, rather than cancer. As you might imagine, he and his family were overjoyed and relieved.

However, two weeks after this surgery, he developed a liver abscess – an encapsulated tissue infection. Surgeons operated to remove the abscess. Two days later, test results revealed that the abscess was caused by a fungus called Candida that was resistant to echinocandins, our most powerful drugs against this fungus.

The patient underwent multiple surgeries and received various antibiotics thereafter, but his abscess kept growing back. He died four weeks after the first surgery to remove the abscess.

The cause of death was sepsis due to his echinocandin-resistant Candida infection, which, at the time, was uncommon in the U.S. This tragic case demonstrated to me firsthand the devastating impact of drug-resistant fungal infections.

In the years since, I have cared for over a dozen patients who have died due to antibiotic-resistant fungal infections. On Nov. 13, 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a report on antibiotic resistance threats in the U.S., warning that drug-resistant fungi have become major public health problems.

The new report revealed that 18 microorganisms cause almost 3 million antibiotic resistant infections and 35,000 deaths annually. For the first time, this report includes several antibiotic resistant fungi: Candida auris, other drug-resistant Candida (as in my patient above) and azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus. These resistant fungi are especially threatening because only three classes of antifungal medicines are currently available.

Antibiotic-resistant fungi?

We have heard a lot in recent years about the public health crisis of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, but less attention has been paid to antibiotic-resistant fungi.

In part, this is because fungi became common causes of disease only over the past 30 years. During this time, the risk for serious fungal infections rose as more people suffered weakened immune systems stemming from increased bone marrow and organ transplantation, new drugs to treat cancer and other diseases, and complex surgeries.

The widespread use of more potent antibiotics to treat resistant bacterial infections also has contributed by creating less competition for fungi to grow in human tissues.

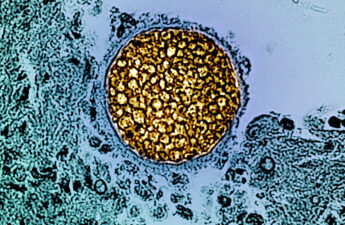

Fungi include yeasts, which grow as spherical cells; and molds, which grow as elongated, tubular cells. Both yeasts and molds are more closely related genetically to humans than they are to bacteria. Therefore, it is hard to develop antibiotics that attack fungi without damaging human cells.

Candida are yeasts that commonly cause skin rashes, urinary tract infections and vaginal infections. However, they are also the third-leading cause of sepsis and other life-threatening infections in U.S. hospitals.

Candida auris was discovered in 2009, but it was almost never encountered in a medical setting until 2015, when numerous infections suddenly occurred on multiple continents. It is now one of CDC’s five most “urgent threats” for two principal reasons.

First, it demonstrates very high-level antifungal resistance. Ninety percent of strains are resistant to fluconazole, the frontline antifungal in many countries; 30% are resistant to two antifungal classes; and between 3% and 5% to all antifungals.

Another reason that the CDC is concerned about C. auris is that it has the unique ability to spread from person to person through contact with hands and clothes of health-care workers or contaminated medical devices. It also persists outside of humans in health-care environments, and causes large, long-standing infectious outbreaks. C. auris is a remarkably robust organism that can survive standard disinfection methods, high temperatures and salt solutions that kill other microbes.

Since the first U.S. case in 2016, C. auris has caused more than 800 infections in 13 states. CDC and local health departments currently are working to contain numerous health-care outbreaks. It is unclear why this fungus has arisen now, although climate and other environmental changes may have played a role. Likewise, it is unclear how widely C. auris will expand in the U.S. or globally.

It’s not just C. auris we need to worry about

Other drug-resistant fungi in the Candida family are also considered “serious threats” by CDC. These strains cause more than 34,000 infections annually, more than are caused by C. auris, but they are less likely to spread from person to person and cause outbreaks. Nevertheless, deeply invasive C. auris and other drug-resistant Candida infections are similar in severity, resulting in the death of 40% of patients.

Another dangerous fungus species the CDC singled out is Aspergillus fumigatus, which is a mold found in soil and vegetation that releases spores that most people inhale daily without problems. However, people with weakened immune systems – especially cancer patients or transplant recipients – can develop lung or other organ infections that kill between 50% and 75% of infected patients.

Azole antifungals are the only drugs that kill A. fumigatus without causing serious side effects. Azoles also are used widely in agriculture. Azole-resistant A. fumigatus infections are most common in Europe, where they have been linked to agricultural and patient use. Although these infections still are uncommon in the U.S., CDC has placed azole-resistant A. fumigatus on its “resistance watch list” because azole use is so widespread in this country and vulnerable patient populations are large.

Tackling antibiotic-resistant fungi requires many strategies

How is the U.S. fighting antibiotic-resistant fungi? CDC and health departments are leading the way in surveillance for resistance and, in the case of C. auris, outbreak containment and prevention. Containment involves rapid and accurate diagnosis of C. auris infections, and the use of hospital gowns, gloves, equipment and cleaning materials that reduce the likelihood of spreading the fungus.

Various U.S. government agencies have funded research that is leading to new antifungal drugs and improved diagnostic tests.

Organizations that grade the quality of medical care for the public now require health-care facilities to have antibiotic stewardship programs that reduce inappropriate prescribing and development of resistance.

Efforts are underway also to control antibiotic use in agriculture and animals, since resistance cannot be tackled by only focusing on human medicine.

CDC and other U.S. agencies are working closely with international partners, because antibiotic-resistant microbes do not recognize geographic borders.

Finally, the crucial first step in tackling a problem is to recognize it, which is why the CDC report on antibiotic resistance threats is so important.

Cornelius (Neil) J. Clancy, Associate Professor of Medicine and Director of Mycology, University of Pittsburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.