Simon F. Haeder, Pennsylvania State University

Collectively, health care is our biggest industry. And, health care has long been one of the most politically contested issues. Partisan wrangling over health reform has perhaps been the most acrimonious issue in Americans politics, exemplified by the failed Clinton health reform efforts in the 1990s and the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010.

Most Americans are befuddled by it, and the political debate surrounding it only makes it more confusing.

You have no doubt heard these terms bandied about: Universal coverage, public option, “Medicare for All,” single-payer. What do these terms mean, and why do they matter going into the Presidential race in 2020?

Universal coverage: Getting everyone covered

Universal coverage refers to health care systems in which all individuals have insurance coverage. Generally, this coverage includes access to all needed services and benefits while protecting individuals from excessive financial hardships. Most Western nations fall into this category.

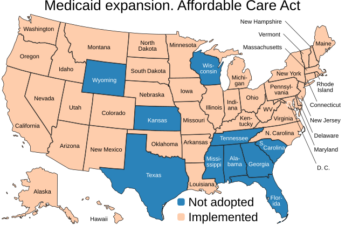

The U.S. serves as the notable exception, with millions of Americans remaining uninsured. The Obama administration touted the passage of the Affordable Care Act as a step toward “near universal coverage.” This differs markedly from Bill Clinton’s proposal in the 1990s which made covering all Americans a centerpiece.

Practically, there is no single pathway to universal coverage. Countries that have achieved it have done so in diverse ways. This includes approaches ranging from private to public insurance and delivery systems, or hybrids of both.

From a policy perspective, achieving universal coverage is a worthwhile goal. There is ample evidence that insurance coverage generally improves the health of individuals. Perhaps equally important, insurance coverage serves as an important protection from financial destitution.

Yet, insurance coverage does not necessarily entail having access to health care services, since travel distances or wait times may impede care. Moreover, regulatory loopholes currently expose many individuals with insurance coverage to large out-of-pocket bills.

Single-payer

“Single-payer” refers to financing a health care system by making one entity, most likely the government, solely and exclusively responsible for paying for medical goods and services. It is only the financing component that is necessarily socialized. Single-payer is not necessarily socialized medicine, a medical system wholly owned and operated by government.

Single-payer systems are often hailed by advocates for their administrative simplicity. Moreover, single-payer systems include everyone in the same risk pool. That is, there is no segregation of individuals based on their medical status. Crucially, single-payer systems are able to use their absolute market and budgeting power to hold down costs.

Government is often the dominant but not sole payer. Even in the United Kingdom, whose National Health Service is famously popular, private insurance coverage and private pay options are available.

Conceivably, a limited single-payer system could be confined to providing catastrophic coverage only. However, this would clearly restrict its ability to realize its full market power.

Finally, it is important to note that single-payer systems should not be confused with so-called all-payer systems, like those in existence in Germany. Here, a number of private entities band together to establish common prices for health care services and benefits.

Medicare in name only: ‘Medicare for All’

The most talked-about Democratic health reform proposal, Medicare for All, prominently references Medicare, the insurance program that covers most of America’s seniors. However, simply expanding Medicare to all Americans would lead to a rude awakening for most. Traditional Medicare benefits are rather limited and often carry with them large out-of-pocket payments.

For example, Medicare does not include dental and vision coverage. A premium-based prescription drug benefit was not included until 2003. And it came with the infamous Part D donut hole that exposed many seniors to significant out-of-pocket costs for their prescription drugs.

In essence then, Medicare for All proposals just borrow the Medicare name while implementing a single-payer system in the United States. As proposed by its two most ardent advocates, Senators Bernie Sanders, D-Vt., and Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., Medicare for All would eliminate all private insurance. It would also come with a very generous benefit package, and very limited, if any, out-of-pocket costs.

One particular stumbling block for implementing Medicare for All is that it makes the overall cost of health coverage an obvious focal point. Of course, costs for expanded benefits and coverage expansions would increase expenditures as compared to the status quo. It would also like increase health care utilization.

However, most detrimental from a politics perspective, Medicare for All unifies all of the country’s exorbitant health expenditures, roughly US$60 trillion from 2022 to 2031, in one single budget. This creates the misperception of being overly costly, while mostly just illustrating current costs. It will also entail a major realignment of the health sector with potentially substantial job losses particularly in the insurance sector.

Set for a comeback: The public option

Not all Democrats are arguing for a do-over of the American health care system. Another set of presidential candidates are arguing for an expansion of the Affordable Care Act. Led by former Vice President Joe Biden, these proposals largely retain the existing structure of the health care system.

The proposals include the creation of a “public option.” This type of approach first gained traction during the debate over the Affordable Care Act. Then, Progressive Democrats sought to include a government-run insurer in the ACA marketplaces. This government entity would have competed with regular insurers for customers based on price, providers and benefits for those purchasing insurance on their own.

Yet the Public Option 2.0 is significantly more progressive than its ACA cousin. It would be open to every American, whether they purchase their own insurance or receive it from their employer. This public insurer would also be using its market power to negotiate better prices. Over time, it would likely also function as a wedge to conduct further and more progressive reforms. A potential final outcome might be a single-payer system.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter. ]

Simon F. Haeder, Assistant Professor of Public Policy, Pennsylvania State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.