By Alex Brown, Stateline

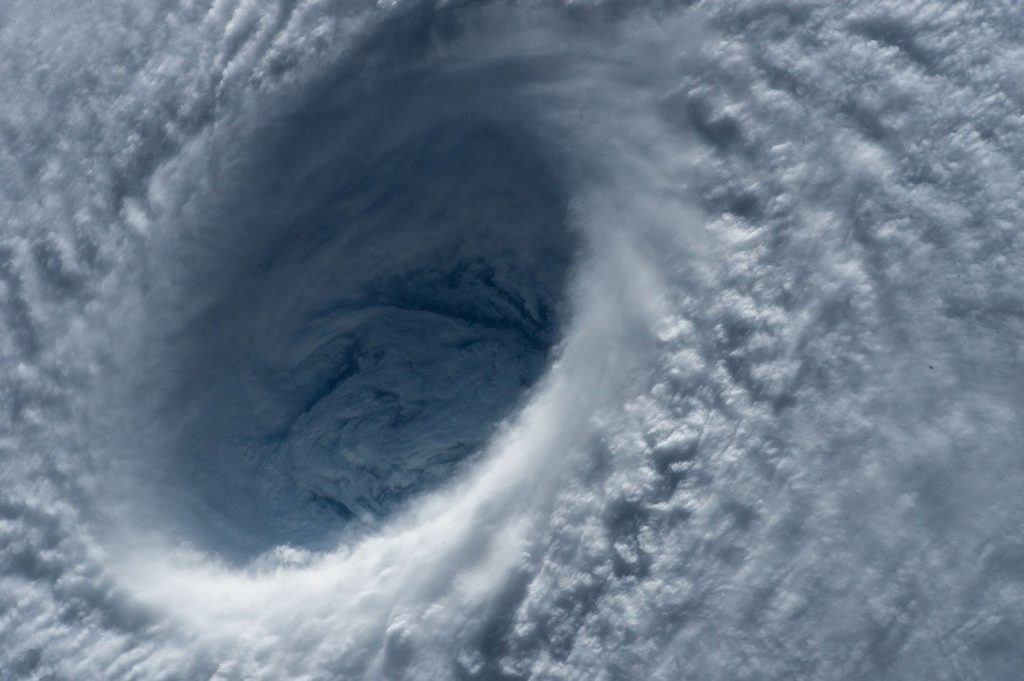

Jim Murley serves as the chief resilience officer for Miami-Dade County, which is experiencing flooding caused by sea level rise and increased hurricane threats. Planning for climate change, he said, is a different beast than typical government work.

“Most of what government does is thinking three to five years ahead,” he said. “[With climate change], we seriously have to think about 2040, 2060, 2100 — that doesn’t happen. We don’t do that for transportation planning, water planning — anything. You have to deal with a lot of uncertainty while at the same time believing the science is taking you on some path among these scenarios.”

Florida’s first-ever chief resilience officer, appointed last year by Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis, is surveying what local governments are doing to develop best practices that can be employed statewide.

Some states’ proposals would borrow massive amounts of money to pay for future work, create new surcharges to bankroll permanent disaster accounts or shift development away from areas prone to disaster. All those plans would come at a cost to state budgets or taxpayers, but supporters say the spending is necessary.

In some states, critics have argued that proposals represent excessive government spending or would inflict economic hardships on residents. Others have countered that some measures don’t go far enough.

Under the status quo, California is projected to face financial liabilities of $100 billion annually by 2050 because of climate change, said Allen, the state senator.

That’s why he is proposing a climate bond, borrowing more than $4 billion to help prevent wildfires and droughts, shore up drinking water and protect coastlines.

The bond would cover a wide variety of projects, some of which would get underway almost immediately, with others to be identified over time.

By investing in resilience projects over the next 10 to 15 years, Allen said, the state would be better prepared for inevitable future disasters. He said California lawmakers have expressed interest in his bill, which would need to pass the state legislature before being sent to voters for approval.

Some Republicans have voiced opposition, including state Assemblyman James Gallagher, who told the Associated Press the state should pay for the work within its existing budget rather than borrowing more money.

Allen, though, thinks the growing challenges require additional long-term investment.

“Anybody who’s thinking about the state of affairs in California right now in terms of any of these problems — wildfires, drought, mudslides, sea level rise — understands that any one of these incidents are part of a broader trend,” Allen said. “Unfortunately, this is the new normal.”

In Washington state, Commissioner of Public Lands Hilary Franz is leading the push for a bill that would establish a dedicated account to help prevent and fight wildfires.

A new surcharge on home and auto insurance policies, estimated to costthe average household $1 a month, would raise an estimated $63 million a year.

“We’re finding increasing numbers of wildfires, we’re seeing an increasing geographical area for those wildfires,” Franz said. “We cannot afford to be complacent or think those are anomalies. … We currently spend on average $153 million a year fighting wildfires. I’d rather be putting $63 million a year toward reducing catastrophic fires.”

Begging lawmakers each year for money for forest health projects and wildfire response resources has usually yielded “zero,” she said. The dedicated account would pay for new resources like additional firefighters, trucks and a helicopter, as well as bankroll the state’s plan to treat forests that have grown too dense and are filled with diseased and dying trees.

Franz’s proposal has Democratic sponsors in both chambers, while Gov. Jay Inslee, also a Democrat, has not yet weighed in. Franz said it won’t be easy to pass the bill over likely opposition from the insurance lobby.

While climate change is shifting conditions in coastal areas, it’s also making the West drier, increasing the likelihood of more frequent and severe droughts. Last year, seven Western states signed, and Congress approved, an agreement to use less water from the Colorado River.

Limits go into effect when the water falls below certain levels. Regional leaders say much more work remains to prepare for drier conditions under climate change.

Flooding Focus

In New York and South Carolina, legislators will consider bills that would prepare for disaster by pushing people to get out of nature’s way. New York put hundreds of millions of dollars into buyouts for homes flooded during Superstorm Sandy. A proposal from state Sen. Joseph Griffo, a Republican, would establish a dedicated fund for buyouts — including in his upstate, inland Mohawk Valley district.

“We need to now have a permanent program in place under an existing agency of the state,” Griffo said. “Right now, we’re reacting, and we’ve done a fairly good job, but it’s case by case. Because this is occurring more regularly, let’s put some more structure together.”

Under his bill, residents whose homes flood repeatedly could lobby their local government to designate the area a flood zone and ask for state money to buy them out and return the land to its natural state. He said the bill has drawn interest, but legislators may need some convincing to approve more state spending despite a $6 billion budget deficit.

South Carolina coastal areas that are prone to flooding and sea level rise have developed rapidly. That has led to a “vicious cycle” in which taxpayers end up paying for disaster relief to rebuild homes that will flood again, said state Sen. Stephen Goldfinch, a Republican.

Such homes can be eligible for buyouts from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, but the homeowner must cover 25% of the cost. Goldfinch has filed a bill that would provide zero-interest state loans for homeowners who don’t have the money on hand to meet the FEMA requirement. He’s hoping for $5 million from the state to get the program underway.

“We’ve experienced unprecedented flooding for five or six years now,” Goldfinch said. “If you add up all the repair costs of fixing a home five or six times, the buyout’s a better solution.”

In Pennsylvania, state Sen. Jay Costa, a Democrat, said climate change is leading to more-frequent landslides in his district, including a major highway collapse in 2018.

“The amount of rain we’ve been experiencing,” he said, “there are communities that have suffered significant landslides that have resulted because of the freeze-thaw cycle that’s here and the changes that have occurred in our weather.”

Costa has proposed a bill to create a state-backed landslide insurance program, while also establishing an assistance fund. The fund would give grants or loans for remediation and stabilization work, while the insurance program would allow homeowners to get coverage that is currently either difficult or expensive to obtain. Both programs would start with $2.5 million.

Costa has introduced the same legislation for several years, and he’s waiting to see whether it gets traction in the legislature in 2020, or whether it will get rolled into Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf’s Restore Pennsylvania plan to address infrastructure needs.

In some coastal areas, there is a debate over whether to remove development from low-lying areas or to invest in costly sea walls. New York City is considering several plans to address flooding, including a $119 billion offshore sea wall that could protect the coast from storm surges but not high tides or storm runoff.

Even that ambitious project, some critics say, does not adequately account for current projections of sea level rise. Federal and state money from both New York and New Jersey likely would be required to pay for the project.

Boston, however, recently scrapped its plans for a sea wall. Instead, Mayor Marty Walsh, a Democrat, envisions using local, state and federal money plus private investment to convert many of the city’s flood-vulnerable areas into parks and green space.

Many states and cities are facing similar questions in 2020, deciding which locations have an urgent need for protection from rising waters, and which areas — like parts of the Florida Keys — are too expensive to save.

Superstorm Sandy flooded a pair of electrical substations in New Jersey, leaving part of state Assemblyman Sean Kean’s district without power for two weeks. Kean, a Republican, questioned the location of the substations, one near the ocean and one near a river. Kean is now pushing a proposal that would require utilities to have flood mitigation plans.

“We need to force the utilities to take the proper action,” he said.

New Jersey announced this week that it will require builders to factor in sea level rise and other effects of climate change to get their projects approved, making it the first state to do so. The regulation is expected to go into place by 2022, forcing developers to consider the long-term implications of climate change, especially for projects along the state’s 130 miles of coastline.

Legislators in Maine will be closely watching the work of the Maine Climate Council, which the legislature established last year to come up with recommendations to reduce the state’s greenhouse gas emissions and prepare for climate change.

Democratic state Rep. Lydia Blume’s proposed commission to assess hazards to coastal communities caused by climate change was incorporated into the council’s mission.

“The idea is that we’re not just waiting for a disaster,” Blume said. “We’re anticipating that we need to make changes so we’re more resilient going forward.”

The council is expected to recommend proposals this year.

Planning Ahead

States also may find it harder to borrow money for future projects if they don’t demonstrate now that they’re thinking ahead about climate change. Credit rating firms such as Moody’s Investors Service have said they are considering the effects of climate change, meaning governments that don’t prepare could see their credit ratings downgraded.

BlackRock, a firm that manages more than $7 trillion in investments, said this month that it would make future decisions based on environmental sustainability, signaling an increased awareness in the financial sector of the effects of climate change.

Gibbons, the adaptation expert, highlighted Minnesota as a leader in climate planning, noting that the state now requires local governments to incorporate projected conditions in their hazard mitigation plans. She noted that most disaster money comes from the federal level and is disbursed after calamities take place. States, she said, need to advocate to change that model.