Nick Longrich, University of Bath

Why do we love? At best, it’s a mixed blessing, at worst, a curse. Love makes otherwise intelligent people act like fools; it causes heartache and grief. Lovers break our hearts, family sometimes drive us mad, friends can let us down.

But we’re hard-wired to bond with each other. That suggests the capacity for love evolved, that natural selection favoured caring for one another. Fossils tell us that love evolved hundreds of millions of years ago, helping our mammalian ancestors survive in the time of the dinosaurs.

Humans have peculiarly complex emotional lives. Romantic love, the long-term bonding between males and females, is unusual among mammals. We’re also unusual in forming long-term relationships with unrelated individuals (friendships).

But humans and all other mammals share one kind of love, the bond between a mother and her offspring. The universality of this attachment suggests that it’s the original, ancestral form of bonding – the first kind of love, from which all others evolved.

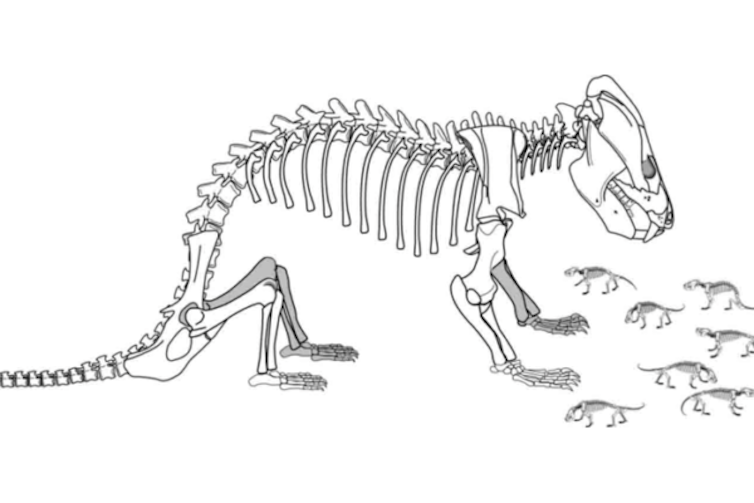

Evidence of parent-offspring bonding appears around 200 million years ago, in the latest Triassic and earliest Jurassic periods. Fossils of Kayentatherium, a Jurassic proto-mammal from Arizona, preserve a mother who died protecting her 38 tiny babies. For this behaviour to exist, the instincts of both mother and offspring first had to evolve.

In primitive animals, such as lizards, parents aren’t exactly parental. A mother Komodo dragon abandons her eggs, leaving hatchlings to fend for themselves. If she ever meets her young, she is likely to try to eat them: komodo dragons are cannibals. The young will instinctively run for their lives upon meeting her – and should.

Common green forest lizard (Calotes calotes)

AntanO via Wikipedia CC

Guarding hatchlings requires that the mother evolve instincts to see her small, helpless offspring as things to protect, not easy prey. Meanwhile, the offspring must evolve to see mum as a source of security and warmth, not fear.

Kayentatherium‘s fossilised mother-child association implies that this instinctive evolution had already happened. But Kayentatherium probably wasn’t a doting mother. With 38 kids, she probably couldn’t feed them, or spend much time on them.

In Welsh rocks laid down in the Late Triassic, we find evidence of more advanced parental care. Here, the proto-mammal Morganucodon shows mammal-style tooth replacement. Instead of endlessly replacing teeth from birth to death –as in lizards and sharks – Morganucodon was toothless as a baby, developed baby teeth, then shed those for adult teeth.

This replacement pattern is associated with lactation. Babies that suckle milk don’t need teeth. So Morganucodon mothers made milk. Providing more care to her young, Morganucodon probably invested heavily in a few offspring, like modern mammals, and would have evolved a correspondingly stronger bond with them. The young, completely dependent on the mother for food, would have developed a stronger emotional attachment as well.

Photo by Gillfoto via Wikipedia, CC license

It’s at this point in mammal history that our mammal ancestors stopped seeing each other as lizards did, exclusively in terms of danger, food and sex, feeling only the primitive emotions of fear, hunger and lust. Instead, they started to care for one another. Over millions of years, they increasingly began to bond, to protect and seek protection, exchange bodily warmth, groom one another, to play with, teach and learn from each other.

Mammals evolved the ability to form relationships. Once they did, this adaptation could be used in other contexts. Mammals could form relationships as family and friends in sophisticated social groups: elephant herds, monkey troops, killer whale pods, dog packs, human tribes. And in some species, males and females formed pair bonds.

Photo by Amoghavarsha JS amoghavarsha.com via Wikipedia, CC License.

Romantic love between men and women is a recent evolutionary development, associated with males helping females care for children. In most mammals, males are absentee fathers, contributing genes and nothing else to their offspring. In our closest relatives, chimpanzees, paternal care is minimal.

In a few species, including beavers, wolves, some bats, some voles and Homo sapiens, pairs form long-term bonds to cooperatively raise children. Pair bonding evolved sometime after our ancestors split from chimps, 6 million to 7 million years ago – probably before the split between humans and Neanderthals.

Love in our DNA

We can guess that Neanderthals formed long-term relationships, because their DNA is in us. That implies that Neanderthals and humans didn’t simply mate. We had children, who themselves became parents, and grandparents, and so on. For the results of those unions to not just survive, but thrive and integrate into their tribe, mixed children were likely to have been born to parents who cared for them – and each other.

Not all encounters between our species were peaceful or pretty, but neither were they entirely violent. Neanderthals were different from Homo sapiens, but enough like us that we could love them, and they, us – even coming from different tribes. A love story worthy of Jane Austen, literally written into our species’ DNA.

There’s an adaptive benefit to love. Today, the ecosystem is dominated by animals with parental care. Mammals and birds, and social insects including ants, wasps, bees and termites, all of which care for their young, dominate terrestrial ecosystems. Humans are the dominant terrestrial animal on Earth.

Photo by Dellex via Wikipedia, CC 4.0

Parental care is adaptive by itself, but by teaching animals to form relationships, it also paved the way for the evolution of sociality and cooperation on a larger scale. Parental care in wood roaches, for example, led one lineage, termites, to evolve vast family groups (colonies) that literally reshape the landscape.

Ants, forming up to 25% of the biomass of some habitats, likely evolved coloniality in the same way. Evolution can be violently competitive, but the ability to care and form relationships allowed for cooperative groups, which became effective competitors against other groups and species.

Caring helps us cooperate and cooperation helps us compete. Humans can be selfish and destructive. But we’ve dominated the planet only because an unparalleled ability to care for one another – for partners, children, families, friends, fellow humans – allowed cooperation on a scale never before seen in the history of life.

Nick Longrich, Senior Lecturer in Evolutionary Biology and Paleontology, University of Bath

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.