People love the idea of 20-minute neighbourhoods. So why isn’t it top of the agenda?

John Stanley, University of Sydney and Roz Hansen, University of Melbourne

We were heavily involved in the consultation program for Melbourne’s long-term land-use plan, Plan Melbourne. The idea that resonated most with many participants was shaping the city as a series of 20-minute neighbourhoods.

People generally loved the thought that most (not all) of the things needed for a good life could be within a 20-minute public transport trip, bike ride or walk from home.

These are things such as shopping, business services, education, community facilities, recreational and sporting resources, and some jobs (but probably not brain surgery).

Creating a city of 20-minute neighbourhoods is a key policy direction of Plan Melbourne 2017-2050. As the plan states:

The 20-minute neighbourhood is all about ‘living locally’ – giving people the ability to meet most of their everyday needs within a 20-minute walk, cycle or local public transport trip of their home.

This planning idea has gained Melbourne recognition in international planning circles. For example, Singapore’s recent Land Transport Master Plan 2040 is based on shaping the city and its transport systems to achieve 20-minute towns within a 45-minute city. Officials who prepared the report have acknowledged to one of us Melbourne’s leadership with the concept.

The concept is not about travel by car. It is about active transport (walking, cycling) and the use of public transport. The goal is that this combination of modes would offer a reasonably sized catchment area in which people, jobs and services, including recreational opportunities and nature, are accessible.

Inner parts of Australia’s capital cities and parts of their middle suburbs already meet a 20-minute neighbourhood test. Very few of the outer suburbs would do so. However, new developments such as the City of Springfield in outer Brisbane are encouraging.

Key ingredients of 20-minute neighbourhoods

If outer suburbs, in particular, are to become 20-minute neighbourhoods, then two key requirements must be met.

First, local development densities need to be increased. This means ensuring minimum density levels of around 25-30 dwellings per hectare, which will better support local activity and services provision.

Consultations with council planners suggest new developments in Melbourne’s outer north, for example, are typically running at about 18 dwellings. The density of developments was about 12 just a decade ago.

Accompanying more dense residential development is the need to integrate a mix of uses within these neighbourhoods. This would bring more jobs and services close to where people live. They would also have a range of housing to support a mix of household types, income levels and age groups.

So we need not just density but also a mix of land uses within a neighbourhood. This is often known as density plus diversity.

Second, local public transport service levels need to be greatly improved. To achieve 20-minute neighbourhoods requires local weekday public transport services running every 20 minutes or better, from around 5am until 11pm (start of last run). That’s a minimum of 55 services per stop per day per direction.

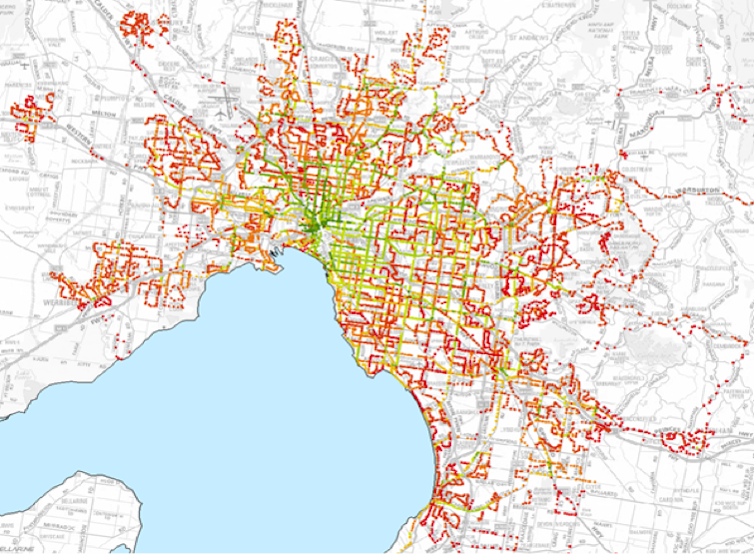

The map below shows very few parts of outer Melbourne have services anywhere near this level.

Source: PTV GTFS feed, Author provided

What would it cost to achieve?

Gross funding increases of about 50% for local public transport services (essentially buses) would be needed to meet this basic service standard for 20-minute neighbourhoods across Melbourne. Based on scaling up the cost of current bus services in Melbourne, we estimate the cost would be about A$250 million a year, or A$4 billion over the long term, in present values.

This is a modest amount compared to current capital commitments for rail. These total A$30-40 billion, depending on what share of the cost of level-crossing removals is attributed to rail. Development of the government’s proposed Suburban Rail Loop around the city will add an estimated A$50 billion. Annual payments for metropolitan train services add A$1.1 billion.

Trains now carry only twice as many passengers as buses do. So the suggestion that an extra A$4 billion or so be spent on bus services, in capitalised terms, is very modest compared to the commitments being made to rail. The amount includes an allowance for infrastructure works to improve operating speeds – such as bus lanes and B-lights, which give buses priority through intersections.

The tram network could make an equally strong argument for extra funding, relative to trains, given the relative passenger loads carried and small new capital program in place for trams (hundreds of millions rather than tens of billions).

Melbourne has recently had a massive jump in spending on capital projects, particularly transport projects. This investment is needed to tackle the backlog from years of neglect and cope with one of the fastest population growth rates of any similar-sized city in the developed world.

The 2019-20 state budget, for example, suggests capital spending will average A$13.9 billion a year over the four years to 2022-23. It was less than A$5 billion a year from 2005-06 to 2014-15.

It’s about more than walkability

In stark contrast, implementation of 20-minute neighbourhoods has been limited to three pilot studies, in Strathmore, South Croydon and Sunshine West. These studies appear to be focused heavily on developing walkable neighbourhoods, rather than on improving access by walking, cycling and public transport, which was the original intent of the idea.

Walkable neighbourhoods are an important part of 20-minute neighbourhoods, but only one part. Increased neighbourhood densities and more mixed-use development across local active transport and public transport catchments, together with better walking, cycling and local public transport opportunities, need far greater attention if 20-minute neighbourhoods are to be created in outer and middle suburbs.

We expect a much stronger focus at the neighbourhood level will deliver very high social, environmental and economic returns from small outlays. But, for this to be achieved, much greater urgency is needed.

John Stanley, Adjunct Professor, Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies, University of Sydney Business School, University of Sydney and Roz Hansen, Adjunct Professor, Deakin University; Professorial Fellow, Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.