By Michael Ollove, Stateline

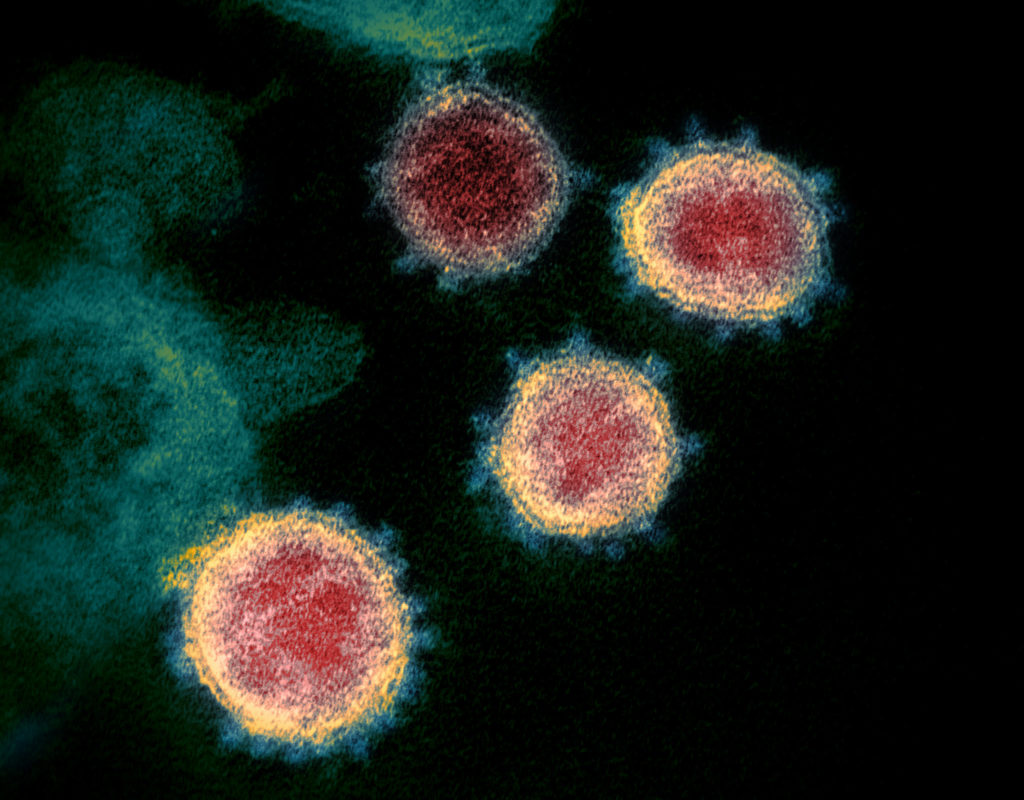

With cases of the new coronavirus multiplying daily, state and local officials have shut down schools and universities, canceled sporting events, concerts and conferences, and even asked houses of worship to stop public ceremonies.

In the space of only days, they have moved to sharply curtail the routines of millions of people.

While many of these actions may have serious consequences for the economy and the collective psyche of Americans, public officials have not hesitated to take bold steps that only a few days ago seemed unimaginable.

“We will take action to protect health where necessary,” said Dr. Rachel Levine, Pennsylvania’s secretary of health.

On Thursday, Republican Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine ordered all public and private schools in the state to close for at least three weeks, beginning at the end of class March 16.

“We thought long and hard about that and we understand the sacrifice this is going to entail but this is the best medical advice we can get from people who study viruses,” DeWine said.

DeWine also directed Ohio’s public health chief to ban gatherings of more than 100 people. The measure exempts grocery stores, public transportation, airports, factories, sporting events without spectators, weddings, funerals and religious gatherings.

Ohio joined Oregon, Michigan, Maryland, Kentucky and New Mexico in closing schools. New York, like Connecticut, Illinois, Ohio and Pennsylvania, banned large gatherings, an edict that will shut down most Broadway theaters.

Republican Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan alerted members of the National Guard to be prepared to help in coronavirus-related activities, including the distribution of food.

While containment of the disease is still the hope in many parts of the country, Levine said she’s not optimistic that is still possible. “We will not be surprised to have community spread,” she said. “Is it likely? Yes.”

Officials in many areas, particularly those hit hardest, such as Washington state, New York and California, have quickly moved from trying to contain the virus to using closures, quarantines and social distancing to slow the spread of the disease.

Their hope is to buy time to develop a vaccine and prevent health systems from being overwhelmed by more patients than they can effectively treat at once.

“If you can slow its spread, you can avoid explosive outbreaks,” said Dr. Nate Smith, the Arkansas secretary of health and president of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials.

“It’s helpful to have guidance from federal partners, but it would be a mistake to try to control this from the federal level,” Smith said. “Communities are different and will be impacted differently.”

Many closure and cancellation decisions by companies, religious institutions and sports leagues have been made voluntarily, without the need for government edicts. For state and local officials, deciding which restrictions to put in place and when is nerve-rattlingly difficult, requiring them to reconcile the irreconcilable: protecting residents’ health while minimizing disruptions and the hardships those could entail.

“These are high-impact decisions,” said Trudy Henson, director of the public health program at the University of Maryland’s Center for Health and Homeland Security.

Levine, the Pennsylvania health secretary, said when officials decide to order closures they hope to make their actions as surgical as possible. An outbreak in one region of the state might spur severe restrictions in that area but not necessarily elsewhere in the state.

Where there are restrictions, she said, it is important to make sure policies are consistent and logical. For instance, she said, “It wouldn’t make sense to close a school, but let its basketball games go on.”

It also doesn’t make sense, Maryland’s Henson said, to close an elementary school where someone was infected but keep other area schools open.

“Kids have siblings who go to other schools, so shutting just one of them doesn’t necessarily solve the problem,” she said.

Each decision has cascading ramifications. If schools are closed and parents cannot work from home, child care becomes a problem. If people are quarantined in their homes, they may have difficulty getting food or other urgently needed supplies.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, ordered the National Guard to New Rochelle, which was designated a “containment zone” because of a large outbreak there. In addition to helping sanitize public areas, members of the National Guard are expected to help deliver food to the homes of those quarantined.

America has not witnessed such broad-based actions to combat an infectious disease since polio epidemics ravaged areas of the country every summer before a vaccine became widely available in the mid-1950s. And not since the Spanish flu in 1918 and 1919 have policymakers had to reconcile public health concerns with the economic health of the country. Such considerations, for example, rarely arise during annual seasonal flu outbreaks.

“As a country, we’ve shown that we’re fine with having 30,000 to 35,000 people die of the flu every year if we still have a vigorous economy,” said Scott Burris, a law professor and director of the Center for Public Health Research at Temple University. “Are we willing to have a robust economy while having another 60,000 to 100,000 deaths from the coronavirus?”

So far, public officials are demonstrating that they are willing to tolerate far-reaching social and economic disruptions to save lives. Making those decisions becomes easier when officials see that their counterparts in other cities and states are doing the same thing. And in the past 48 hours, the wave of cancellations and restrictions, by both public and private entities, has swelled.

Still, there are obvious steps officials have not yet embraced.

For example, it appears no locality has taken the step of shutting down a public transit system, even though buses and subways, with their confined quarters, represent a clear threat in an infectious disease outbreak.

“Public transportation, that is one of the most complicated issues because it affects so many people who rely on it,” Henson said. Not only do tens of millions of people use public transit to get to work and school, she said, but shutting it down also could cut access to health care for the many without alternate forms of transportation.

Another grave challenge for counties, cities and states is protecting the health of those who are incarcerated. They too are in confined spaces where it is difficult to prevent the spread of communicable disease. Rates of infections such as tuberculosis and hepatitis C often are worse in prisons and jails than in the general population.

“It is hard to control once a virus enters into a prison,” said Maria Morris, a senior state attorney with the ACLU’s National Prison Project.

Health care is often poor in jails and prisons, she said, and supplies are lacking for preventing disease spread, notably soap and clean, hot water. Prisons also are likely to have a hard time finding enough space for quarantining prisoners and isolating those who are symptomatic.

Iran temporarily furloughed thousands of inmates this month to try to prevent the spread of the disease in prisons. Morris suggested that American officials should consider releasing some uninfected prisoners.

“They should be thinking of moving people out of prisons now, particularly those who are vulnerable, like older inmates,” she said. “Jails should be thinking about releasing people who are only there because they can’t afford bail. They have to be sensible about this.”

Infectious diseases in prisons and jails don’t remain confined to those institutions, Morris added. Correctional workers as well as released prisoners can carry the disease into communities. “Although we think of prisons as closed environments, they aren’t when we talk about infectious diseases,” she said.