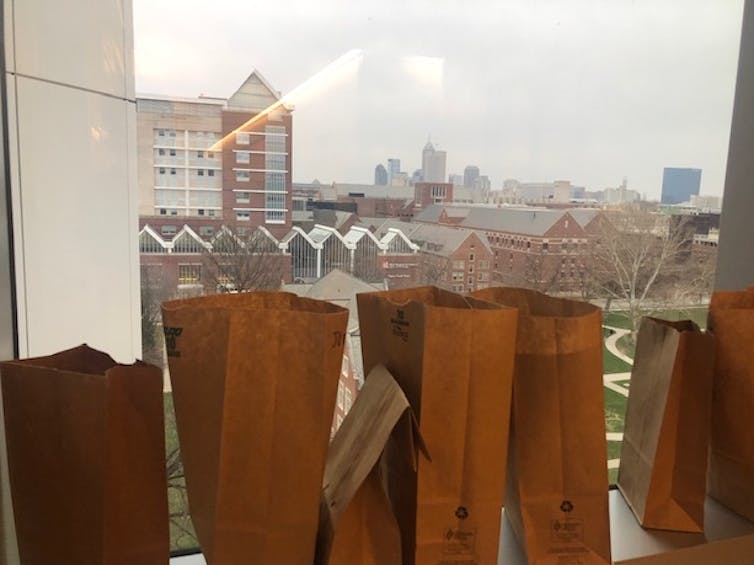

W. Graham Carlos/Indiana University

W. Graham Carlos, Indiana University School of Medicine

The Conversation is running a series of dispatches from clinicians and researchers operating on the front lines of the coronavirus pandemic. You can find all of the stories here.

Brown paper bags line the windowsill of the COVID-19 intensive care unit at Eskenazi Hospital in downtown Indianapolis. The bags are filled with the N95 masks we’re reusing, labeled with the handwritten names of my staff: Patrick, Angela, Brittany. They are mothers, fathers, brothers and sisters.

As of this writing, we are caring for more than double our average number of ICU patients and using more than triple our average number of ventilators. We expect those numbers to keep climbing.

To prevent exposure to coronavirus, we use gowns, gloves, goggles and masks. The N95 mask in particular is critical because it protects front-line hospital staff from aerosols emitted during high-risk procedures, such as placing someone on life support.

One of my roles as the chief of internal medicine and an intensivist working in the ICU is to teach my staff why we are taking steps that we wouldn’t ordinarily take, such as saving their N95 respirator masks in paper bags.

Supplies of protective gear are dwindling. We are worried about the number of ventilators we have available for patients. We don’t talk about supplies in terms of numbers anymore; we talk in terms of days. And I need a way to talk to my staff about this that is both truthful and calming.

My team of nurses, physicians and therapists are selflessly serving patients afflicted with a deadly and highly contagious virus. I need words that work.

Communicating decisions like this is difficult, and I know that what I say and how I say it has never been more important. I prepare myself.

Rationing supplies

“What do we do when we run out?” I am asked frequently, regarding personal protective equipment and ventilators.

Given the effect that SARS-CoV-2 has on the lungs, many patients require mechanical ventilators to infuse enough oxygen into their bodies to keep them alive. These machines use hospital supplies of oxygen and deliver air into the lungs under pressure to open them up.

Ventilators are used all of the time in surgery and critical care, but they are expensive and strictly limited in supply.

Ventilator allocation describes a process in which a committee, typically comprised of three people including an intensivist, follow a predetermined algorithm taking into account a patient’s age, underlying illness and severity of current illness to determine who should get priority to receive a ventilator when there are none left.

The idea is that we would make decisions in advance based on objective data, so we aren’t influenced by bias and emotion when tough decisions have to be made.

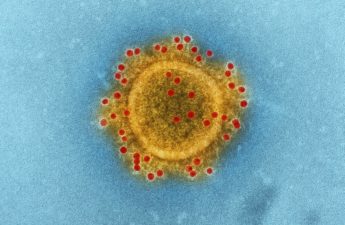

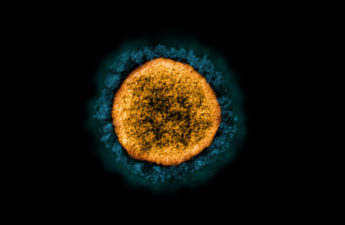

Photo: Indiana University

Hospitals all over the country are preparing their allocation teams and documents, and it is terrifying. We are encouraged to see factories ramping up production of ventilators, but we are still worried. Will they be here in time, or will it be too little too late?

On a national level, I serve the American Thoracic Society as chair of the Section on Medical Education. I have been working on documents to rapidly communicate important information to patients and providers, including two Twitter chats. These serve to increase awareness and share vital information to health care systems and providers worldwide. In addition to interviews on local and national news outlets, I am using social media to share the truth about the virus and advocate for communities to keep social distancing to slow the spread of COVID-19.

I am saying, prepare, but don’t panic.

Now that the virus is endemic with community spread, we are seeing hospitals fill up. Systems to conserve protective equipment, cohort patients with the virus together and keep hospital staff educated are vital.

We should prepare for the “just in case,” in the event that the ventilator supply runs low, by creating allocation teams and electronic medical records that extract data for those teams.

We need to prepare for this to continue. Early estimates considering how the virus acted in China mean we could be looking at surge capacity for hospitals well into April.

We also need to prepare our staffs mentally. Celebrate “wins” when patients get better. Take time to reflect on all that is good.

I look at the brown paper bags lined up next to each other as a symbol of solidarity in mission and purpose. We are all in it together. We have never needed each other more.

[Get facts about coronavirus and the latest research. Sign up for our newsletter.]

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.