Courtesy of Peter Kofinas

By Matt Vasilogambros, Stateline

States are desperate for medical supplies, governors are pleading with the federal government to secure dwindling lifesaving equipment, and the number of novel coronavirus cases continues to rise nationally.

But emerging from this crisis has been a widespread effort by small businesses, university labs and everyday Americans to create personal protective equipment for vulnerable health care professionals who are keeping patients alive and fighting the contagion.

In Illinois, many manufacturers are retooling to make essential medical supplies for local hospitals: N95 masks, hand sanitizer and secure packaging for sending COVID-19 testing samples.

With the encouragement of Democratic Gov. J.B. Pritzker, the Illinois Manufacturers’ Association and the Illinois Biotechnology Association are leading an effort to streamline manufacturing and vet companies for health care providers. Hundreds of companies have reached out, said Mark Denzler, the manufacturing group’s president and CEO.

“It’s a wartime-like effort,” he said.

There are countless examples of collaboration between businesses and medical professionals, from a Kansas brewery making thousands of gallons of hand sanitizer, to a university lab in Wyoming 3D printing face masks to a small business in Texas makingventilation devices.

“It’s been inspiring to see the number of local manufacturers help local hospitals and communities,” said Priya Bathija, vice president for strategic initiatives at the American Hospital Association. “We’re seeing a lot of interest from people who don’t typically produce personal protective equipment.”

Bathija has led a nationwide call to action to increase that production, facilitating partnerships between manufacturers and hospitals, providing equipment designs and specifications and guiding donated equipment to hospitals in need.

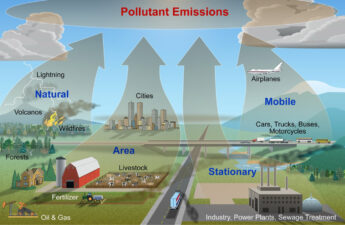

Hospitals are going through more personal protective equipment than normal, since a lack of adequate testing forced health care providers to treat every patient as if they have the virus, she said. In addition to shortages in the U.S. federal stockpile, much of the needed equipment is manufactured in China, which has led to delays as that country deals with its own crisis.

The widespread shortages of personal protective equipment, known as PPE, has put staff and patients at risk, according to an inspector general report this monthto the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Hospitals, the report found, are turning to new, nontraditional sources of medical equipment.

“We’re playing catchup,” said Julie Letwat, a Chicago-based health care counsel for national law firm McGuireWoods who works with pharmaceutical companies and professional medical associations. “We’ve been grossly behind.”

President Donald Trump has blamed states for not building their own equipment stockpiles, saying last week, “We’re a backup, not an ordering clerk.” But governors from both parties, from Wyoming to Illinois, have been critical of the federal government’s handling of the medical supply shortage.

The shortage in New York is so acute that Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed an executive order last week that would allow the state to redistribute ventilators to hospitals that need them the most. California, Oregon and Washington have sent ventilators to New York. Throughout the crisis, Cuomo has been one of the more vocal critics of the federal government’s response in closing the supply gap.

“There’s not enough in the federal stockpile to take care of New York and Illinois and Texas and Florida and California,” he said last week. “It’s not an option.”

States should not be competing against one another for invaluable supplies, said Bob Griffin, founding dean of the College of Emergency Preparedness, Homeland Security, and Cyber Security at the University at Albany and a former federal under secretary and local emergency management director. Instead, it is the responsibility of the federal government to coordinate the logistical and equipment procurement effort, he said.

From Griffin’s time in both the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and in local emergency management, he found that pandemics are the hardest scenarios to deal with — they hit across regions and strain resources.

A tenuous relationship between the federal government and the states now only exacerbates those problems, he said, and has forced businesses, university labs and average people to step up and fill the supply gap.

“One of the bright spots in this gloomy forecast is the entrepreneurship and creativity of American communities,” he said. “And there are those small, but incredibly important, random acts of kindness that we as a society need to continue to practice.”

Americans are working as fast as they can to meet this urgent need for materials.

Closing the Supply Gap

Last month, Mike Krause, the executive director of the Tennessee Higher Education Commission, got a call from Republican Gov. Bill Lee asking how many 3D printers the state’s universities had on hand. Krause said 343. Lee then asked what they could do with them. Twelve hours later, Austin Peay State University had an answer: face shields that protect scarce N95 masks for nurses and doctors.

Three days after the governor’s call, public schools across the state — from technical colleges to their flagship university — began producing thousands of face shields. Within 10 days, they made 9,100.

While it was a bit of a learning curve to get things going, Doug Catellier, project manager at Austin Peay’s Geographic Information System Center, said he and around 15 staff members and students are using the university’s dozen 3D printers and a laser cutter with a goal of making 15,000 face shields for the state.

“I have a lot of friends who are doctors and nurses,” Catellier said. “So, I hear from them all the time that they need these. It’s a good feeling to know that the effort you’re putting in, and the efforts of the students, is going to a good and worthy cause and helping out.”

Elsewhere in the Volunteer State, automotive component and system manufacturer DENSO also is making thousands of face shields designed to protect local health care workers.

Within three days of starting production, the Maryville facility donated 30 prototypes to Blount Memorial Hospital, said corporate spokesman Andrew Rickerman. The facility is ramping up production and will donate each item it makes.

Other companies throughout the country are producing more complex medical equipment like ventilators — life-support machines that pump oxygen into an infected patient’s lungs and filter carbon dioxide. A report earlier this month from the Democratic majority on the U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Reform found that the critical shortage of ventilators is expected to worsen.

It is important for companies to collaborate with experts and other experienced manufacturers on these devices, said Tim Myers, chief business officer for the American Association for Respiratory Care, a nonprofit that supports cardiopulmonary care professionals. “Most of these ventilators are highly sophisticated, microprocessor-controlled machines with monitors and alarms,” he said.

In California and Delaware, fuel cell manufacturer Bloom Energy has converted storage space in its facilities to create new lines for refurbishing out-of-service ventilators. Company officials work closely with state agencies to identify suppliers of older ventilators and with biomedical engineers at Stanford Health Care to test the functionality of the refurbished ventilators. Around two dozen staff work on this project.

So far, the company has refurbished nearly 1,000 ventilators. Erica Osian, public relations manager at Bloom Energy, anticipates the company soon will begin producing 2,000 every week. This allows other manufacturers to focus on building new machines without having to worry about older ones.

“The focus right now is doing what we can to help our communities in this time of crisis,” she said. “This is how we can help, so this is what we’re doing.”

Other companies such as Ford and General Motors are partnering with GE Healthcare to build new ventilators in shuttered car plants, adding to around 10,000 ventilators in the federal stockpile available for emergency deployment.

Partnerships across industries have been crucial in trying to close the supply gap.

Additional Collaborations

When the novel coronavirus intensified in Italy last month and it became inevitable the global pandemic would come to the United States with force, engineers at the University of Maryland got to work on developing medical equipment that hospitals would soon desperately need.

They had the chemical and engineering expertise. They had the partnerships with hospitals in the Washington, D.C., and Baltimore area. They knew how to quickly develop medical equipment prototypes that meet Food and Drug Administration standards. And they had 3D printers that were ready to use.

Over the past several weeks, the university and its private sector partners have developed and begun distributing customizable face shields, polymer plastic masks, hand sanitizer and hands-free door latches.

“People are jumping in and trying to contribute,” said William E. Bentley, director of the Robert E. Fischell Institute for Biomedical Devices at the University of Maryland. “It’s just huge.”

One of those partners is biomedical startup ActivArmor. In normal times, the Pueblo, Colorado-based company makes 3D-printed casts and splints that are customizable and removable. But during this global pandemic, it upended operations to begin making custom-fitted face shields for medical professionals that block harmful airborne particles that could carry the deadly contagion.

When the crisis hit and U.S. hospitals began reporting a staggering shortage in personal protective equipment, the company found itself well-positioned to fill this supply gap, said Diana Hall, president and chief operating officer. The company already had a partnership with the University of Maryland and its 3D printers.

The university also has begun mass producing thousands of bottles of hand sanitizer for first-responders. Peter Kofinas, the chairman of chemical and biomolecular engineering and one of the leads on the project, said that while his lab has had some problems getting materials delivered since the university is closed, the projects have been a no-brainer. What has been unusual is the way he began this work.

While participating in martial arts training last month at 2nd Gear Brazilian Jiu Jitsu in Laurel, Maryland, he heard from his training partner and career Montgomery County firefighter Oscar Montalvo that his and other firehouses were running low on hand sanitizer, which is essential to keeping them safe on emergency calls.

Soon, Montalvo’s Gaithersburg firehouse received 100 bottles from the university. Montalvo said he was lucky to know Kofinas.

Those personal connections have become invaluable in this fight to produce much-needed medical equipment. Throughout the country, countless people have used their personal 3D printers to contribute to the effort, including Jordan Plieskatt and his 12-year-old son, Mason, in Alexandria, Virginia.

Father and son are members of the DC Mutual Aid Network, a grassroots group of people 3D printing thousands of face shields for health care workers and delivering them to local hospitals. As they recruit more people in the region to their effort, the group hopes to produce 10,000 every month.

“It almost sounds ridiculous that community members have to make homemade equipment for health care works, but that’s the reality of it,” Plieskatt said.

The two of them have made approximately 350 face shields over the past two weeks.

“Seeing them wearing what you made brought tears to our eyes. You can make a difference.”

Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.