By Matt Vasilogambros, Stateline

Nikia Londy’s employees are afraid to come back to work.

The owner of Intriguing Hair, a salon in Boston’s Hyde Park neighborhood, thought her stylists would be eager to return. But they don’t feel safe, she said.

Like other states, Massachusetts has released standards businesses must follow to reopen after two months of quarantine. Among the dozens of requirements, every employee at salons and barbershops must wear face masks and eye protection.

Faced with choosing vendors despite knowing little about the equipment, Londy is struggling to procure this safety gear before reopening May 25.

“I don’t even know where to get that,” she said.

As every state gradually lifts coronavirus restrictions, employers are scrambling to get enough protective equipment to create a safe work environment. Buying safety equipment, however, has created additional challenges for businessowners, who may be unfamiliar with vendors and potential scammers.

Adding to that concern, a recent Washington Post-Ipsos poll found that nearly 6 in 10 Americans fear exposing their households to the novel coronavirus upon returning to work. Some states, such as Connecticut and Maine, have delayed reopening some businesses out of fear it might be too soon and dangerous.

Maine has allowed barbershops and hair salons to reopen across the state, requiring face masks and spread-out chairs. But that doesn’t mean stylists were eager to get back to work.

Julia Perry, a Brunswick, Maine-based cosmetologist, has been frustrated with that state’s plan to reopen. It is too soon, she said. It puts her health and the health of her clients at risk. She is still waiting to receive an order of surgical masks.

She has resisted beginning her services thus far. But if she doesn’t start soon, she fears she will lose many of her 250 clients. “It’s a real slap in the face,” she said. “I don’t think the state is taking us seriously. There’s not enough testing. We feel like guinea pigs.”

Given these hurdles, some states, counties and nonprofits have launched efforts to help businesses find and buy protective equipment.

All employers are required by federal law to identify potential hazards in the workplace and take steps necessary to protecting their employees, said Gina Fonte, a Boston-based senior counsel at international law firm Holland & Knight who focuses on workplace safety.

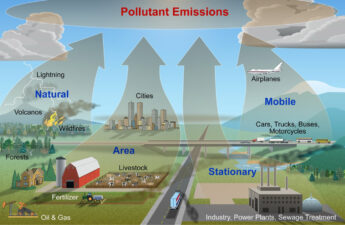

In the era of COVID-19, employers will have to pay even closer attention to those standards set by the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), as the pandemic uniquely threatens workplaces across industries, she said. For example, office workplaces may require face masks and hand sanitizer now, which employers would be obligated by law to provide, she said.

That adds a hurdle for companies and employers, which now must source and buy personal protective equipment, known as PPE.

“The fact is that it’s hard to find personal protective equipment and more people need it,” Fonte said. “[COVID-19] certainly did create a lot of new PPE and safety requirements for employers and workplaces that might not have been prepared to deal with these issues.”

Nationwide, workers already have filed thousands of COVID-19-related OSHA complaints during the pandemic. In Massachusetts alone, hundreds of essential workers filed federal complaints about their safety, including not being provided PPE and being forced to work in grocery stores, at medical facilities and for delivery services beside sick colleagues.

Until there is a vaccine, proven treatment or cure for the virus, there will be concern in the workplace about safety or potential exposure to the illness, Fonte said. Employers must balance a real desire to help the economy with the safety and health of their employees, she said.

States such as Maryland saw an opportunity to help both small businesses buying protective equipment and manufacturers selling it. The Old Line State earlier this month launched a platform to connect businesses within the state, vetting suppliers to make it easier for buyers.

“It really created a way for the local community to find companies in the state to fill those needs,” said Michael Kelleher, executive director of the Maryland Manufacturing Extension Partnership, a nonprofit that worked with the state’s Department of Commerce for this effort.

Similar efforts are underway in Colorado, Kentucky and Pennsylvania.

Other state and local governments are providing some safety equipment for free.

Luke Bosso, chief of staff for the Indiana Economic Development Corporation, saw firsthand how difficult it was for the state to get enough PPE to hospitals at the height of the outbreak. If he was having a hard time buying 1 million masks, negotiating with domestic and international vendors, surely small businesses throughout the state were going to have trouble finding 10 masks, he thought.

Earlier this month, the state launched an exchange for businesses with fewer than 150 employees to receive free bundles of nonmedical-grade face masks, hand sanitizer and face shields.

“We recognize this is really new for companies in the United States, to have their employees wear masks and have hand sanitizer readily available,” he said. “Anytime you open a new supply chain, you’re going to have some difficulty procuring that stuff.”

Ten days into its effort, the state has provided packages of safety supplies to 20,000 local businesses. The state will keep its marketplace open until at least mid-June, Bosso said, with the goal of serving 50,000 small businesses. The state is using federal CARES Act dollars.

Similar efforts are underway at local levels.

As Orange County, Florida, planned for its Orlando-area businesses to reopen, Danny Banks, the county’s director of public safety, heard from many businessowners who could not find masks and hand sanitizer for their employees. Several of their workers, he heard, threatened not to come back unless they had safety equipment.

Wary of infection numbers going up, the county decided to procure the safety supplies itself and provide them to businesses. In the past week, 100 county employees, mobilized from various departments, moved 1.8 million masks and 225,000 small bottles of hand sanitizer to 12,000 local businesses, from barbershops to nail salons to small grocery stores.

For businesses that have struggled to pay rent or furloughed employees, the supplies are like a shot in the arm, Banks said.

“We’ve got an opportunity to help small businesses reopen,” he said, “but we really have a responsibility to help them reopen safely.”

Employee safety has been a top concern for Sheldon Lloyd, CEO and co-owner of City Fresh Foods, a Roxbury, Massachusetts-based caterer with 130 employees that hires from and serves low-income communities in the Boston region.

At the beginning of the outbreak, Lloyd could not get protective equipment for his workers, who were packing food in close proximity and delivering 14,000 meals door-to-door every day — sometimes to senior citizens, who are especially susceptible to the virus. He made his own sanitizer, masks and wipes, while also breaking up shifts to space people out and discontinuing office coffee to cut down on staff interactions.

Only in recent weeks has he received some supplies from donations and the city of Boston. His first order of face shields arrived last week.

Lloyd worked every connection he had to get safety supplies, calling vendors, the state and nonprofits. But everyone was in the same boat — there was a national shortage. He wishes there had been a central location where he could have sourced these materials from the beginning.

“It was nerve-wracking,” he said. “It was a very, very surreal experience — trying not to kill myself or kill somebody else.”

Lloyd just signed up for Protect MA, a new online portal that hopes to avoid many of the problems he faced over the past two months. Launched by the nonprofit Black Economic Council of Massachusetts, the initiative connects black- and Latino-owned suppliers of safety equipment with other black- and Latino-owned businesses looking to reopen after a months-long stay-at-home advisory.

Segun Idowu, the council’s executive director, said minority businesses in the Bay State were hit particularly hard during quarantine, especially restaurants, salons and gyms. A study by the Brookings Institution last month showed that COVID-19 may disproportionately affect businesses owned by minorities and women because of existing economic barriers.

And now that businesses are reopening, many of Idowu’s 300 member businesses are attempting to find safety equipment through word of mouth.

“That is no way to cover thousands and thousands of minority businesses that are going to need this across the state,” he said. “We know that it is important to have a one-stop shop for this stuff.”

Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.