By Edward Lempinen, University of California, Berkeley

Emergency health measures implemented in six major countries have “significantly and substantially slowed” the spread of the novel coronavirus, according to research from a UC Berkeley team published today in the journal Nature.

The findings come as leaders worldwide struggle to balance the enormous and highly visible economic costs of emergency health measures against their public health benefits, which are difficult to see.

In the first peer-reviewed analysis of local, regional and national policies, the researchers found that travel restrictions, business and school closures, shelter-in-place orders and other non-pharmaceutical interventions averted roughly 530 million COVID-19 infections across the six countries in the study period ending April 6.

Of these infections, 62 million would likely have been “confirmed cases,” given limited testing in each country.

Continuation of these policies after the study period has likely avoided many millions more infections, according to lead author Solomon Hsiang, director of Berkeley’s Global Policy Laboratory and Chancellor’s Professor at the Goldman School of Public Policy.

“The last several months have been extraordinarily difficult, but through our individual sacrifices, people everywhere have each contributed to one of humanity’s greatest collective achievements,” Hsiang said. “I don’t think any human endeavor has ever saved so many lives in such a short period of time. There have been huge personal costs to staying home and canceling events, but the data show that each day made a profound difference. By using science and cooperating, we changed the course of history.”

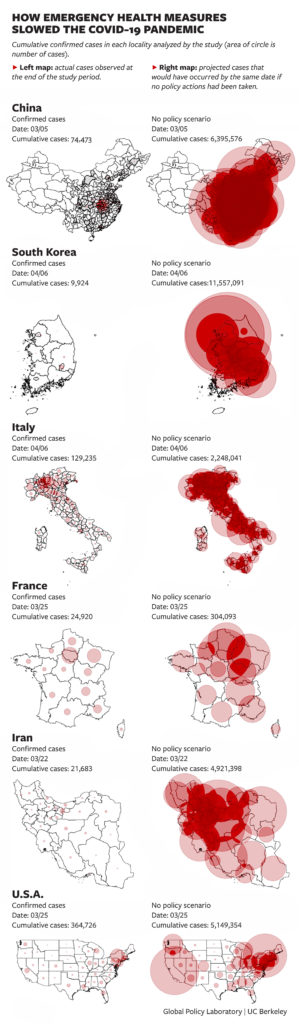

Maps based on detailed data show how emergency policies helped control the pandemic — and what would have happened without those measures. Click the image to enlarge. (UC Berkeley image by Global Policy Lab and Hulda Nelson)

The study evaluated 1,717 policies implemented in China, South Korea, Italy, Iran, France and the United States in the period extending from the emergence of the virus in January to April 6, 2020. The analysis was carried out by Hsiang and an international, multi-disciplinary team at the Global Policy Laboratory, all working under shelter-in-place restrictions.

Recognizing the historic challenge and potential impact of the pandemic, “everyone on our team dropped everything they were doing to work on this around the clock,” said Hsiang.

Before intervention, exponential growth

The novel coronavirus emerged in late 2019 in Wuhan, China, and in a matter of weeks, spread around the globe. The medical impact was compounded by the devastating economic slowdown. How great was the risk posed by the virus?

Without comprehensive data on policy interventions, it would not have been possible to gauge how quickly it would have spread naturally. But according to the new study, infections were growing 38% per day on average — doubling roughly every two days in each country — before crisis policies slowed the spread.

Today, global cases are nearing 7 million, with just over 400,000 dead. But the UC Berkeley research suggests that the toll would have been vastly worse without policy interventions.

“So many have suffered tragic losses already. And yet, April and May would have been even more devastating if we had done nothing, with a toll we probably can’t imagine,” Hsiang said.

“It’s as if the roof was about to fall in, but we caught it before it crushed everyone. It was difficult and exhausting, and we are still holding it up. But by coming together, we did something as a society that nobody could have done alone and which has never been done before.”

The life-saving impact of policy

Large-scale policies were initially deployed based on recommendations from epidemiological modeling teams that simulated the spread of COVID-19 under different sets of assumptions. But since both the pandemic and policy responses are unprecedented, nobody knew in advance which policies would work or how effective they would be.

The UC Berkeley team studied how quickly the number of COVID-19 infections grew within different locations before and after policies were enacted, for the first time measuring how much each policy contributed to flattening the curve.

Solomon Hsiang, director of Berkeley’s Global Policy Laboratory and Chancellor’s Professor at the Goldman School of Public Policy, describes the life-saving impact of emergency pandemic policies in six countries. (UC Berkeley video by Roxanne Makasdjian)

The researchers analyzed data on the number of confirmed cases in each country, based on local testing procedures. But to account for limited testing, they also calculated what the total infection rates likely would have been if everyone had been tested.

“Our results suggest that ongoing anti-contagion policies have already substantially reduced the number of COVID-19 infections observed in the world today,” the researchers wrote. “Based on these results, we find that the deployment of anti-contagion policies in all six countries significantly and substantially slowed the pandemic.”

During the period of study, the impact of policies the six countries is striking, both in statistical and human terms:

- China: policies averted roughly 37 million more confirmed cases, corresponding to 285 million total cases (including confirmed cases)

- South Korea: 11.5 million confirmed cases and 38 million total cases averted

- Italy: 2.1 million confirmed cases and 49 million total cases averted

- Iran: 5 million confirmed cases and 54 million total cases averted

- France: 1.4 million confirmed cases and 45 million total cases averted

- United States: 4.8 million confirmed cases and 60 million total cases averted

The study did not estimate how many lives might have been saved by the policies because, with so many infections, fatality rates would be much higher than anything observed to date.

The UC Berkeley team based its conclusions on an exhaustive collection of data, gathered from hundreds of sources in several languages. The researchers traced the arrival of the virus in a given country, then used data to track how the cases grew over time. Noting when major policy interventions occurred, they were able to study how the numbers changed.

Members of the team come from China, France, South Korea, New Zealand, Singapore and the United States, and their cultural knowledge and language skills helped the team to tap a deep trove of data.

Fine-tuning future policy

An objective of the study was to understand which policies have played the greatest role in slowing the pandemic.

The team found that home isolation, business closures and lockdowns (a component of emergency declarations in some countries) often produced the clearest benefits. Travel restrictions and bans on gathering had mixed results, with large effects in some countries — Iran and France, respectively, for example — and less clear benefits in countries such as the United States.

The researchers did not find strong evidence that school closures had an impact in any country, but they cautioned that their finding is not conclusive, and that more research should be used to inform school policies.

The team found that while some policies change behavior immediately and may have quickly led to small benefits, it took three weeks, in general, for policies to achieve their full impact on the spread of COVID-19. Now that some countries are relaxing policies, Hsiang said, “we might reasonably expect signals of any renewed spread to emerge on a similar two- to-three-week time frame.”

Lessons for other countries

Lessons from the UC Berkeley study can be valuable to more than 180 other countries not included in the analysis. While some countries have already reduced infection rates, confirmed cases in many others — such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Brazil, India, Pakistan, Peru, Mexico, Nepal and Nigeria — are just starting to take off.

For these countries, one finding of the study stands out: “Our analysis of existing policies indicates that seemingly small delays in policy deployment likely produced dramatically different health outcomes.”

The research team has made additional material, as well as data and code, available to the public.

UC Berkeley co-authors of the research are Daniel Allen, Sébastien Annan-Phan, Kendon Bell, Ian Bolliger, Trinetta Chong, Hannah Druckenmiller, Luna Yue Huang, Andrew Hultgren, Emma Krasovich, Peiley Lau, Jaecheol Lee, Esther Rolf, Jeanette Tseng and Tiffany Wu.