By Christine Vestal, Stateline

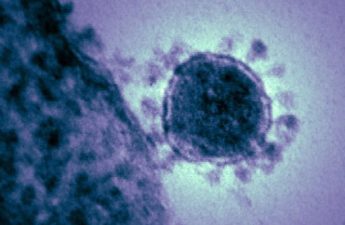

The day before a planned visit from President Donald Trump earlier this month, a technician swabbed Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine to test him for COVID-19. Within 15 minutes, a plus sign for a positive result appeared on the screen of a desktop device the size of a digital alarm clock.

Later that day, however, the Republican governor was tested using a laboratory analysis, which produced a negative result. DeWine’s high-profile testing error raised concerns about the reliability of so-called rapid result antigen tests. But the mishap did little to dampen enthusiasm for the cheap, fast and easy-to-use tests.

Many, including members of the Trump administration’s coronavirus task force, say rapid result tests have the potential to cure the nation’s COVID-19 testing shortage — a problem that has hobbled public health efforts to control the virus from the beginning.

At the same time, public health officials worry that the less sensitive tests — which are increasingly used in doctor’s offices, nursing homes, jails, schools and workplaces — could muddy the surveillance data epidemiologists rely on to monitor the spread of the virus.

They question whether users of the tests outside medical settings will be able to accurately report results from what is projected to be millions of antigen tests every day.

“It’s a very serious problem,” said Dr. Jeff Engel, senior adviser and former executive director of the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, which along with the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sets standards for state reporting of infectious disease data.

“Since the industry started scaling up production of antigen tests in June and July,” Engel said, “it has changed the entire environment of COVID testing and surveillance.”

Engel and other experts acknowledge that antigen tests and a new fast-acting saliva test approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration this month could allow the nation to get back to more normal life, even before a vaccine is widely available. Ultimately, the tests are expected to become so cheap and plentiful that every American could have a supply of them to use at home.

But individual users still would be expected to report both positive and negative results to their local health authorities.

Earlier this month, Engel’s organization and the CDC called on state and local public health agencies to record positive antigen test results as possible COVID-19 cases and convert the cases to confirmed status only after a more accurate test is performed.

Although an estimated 10 million antigen tests have been performed in the United States since June, only about 500,000 have been recorded in daily test counts, according to Alexis Madrigal, a journalist and founder of The Atlantic’s COVID Tracking Project.

Only six states — Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Texas and Utah — appear to be accounting for antigen tests conducted in the state, he said. As recommended by the CDC, the states are not reporting positive cases unless confirmed by a laboratory test.

“It is a huge policy issue, and it’s a huge problem,” Madrigal said. “These rapid point-of-care tests are a remarkable public health tool, but they also make it difficult to track how much testing is being done.”

Jennifer Nuzzo, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, which also tracks state and local COVID-19 data, agreed. “Rapid result tests are potentially going to be helpful,” she said. “But we need to figure out how states are going to use them and how they’re going to report the data.

“One of the reasons we’re in this mess is that states are making high-stakes decisions about whether to restrict travel and open or close schools and businesses based on positivity rates,” she said. “We have to hope they’re calculating them with the correct data.”

Positivity Rates

Ever since the pandemic hit U.S. shores early this year, and it became clear that tests were in short supply, governors have been competing to stockpile test kits and touting their daily testing numbers.

“I’m not convinced that a lack of technology and supplies is our only testing problem,” Nuzzo said. “The absence of a national strategy is a far greater challenge. We need to figure out what patient populations we want to use these new tests on and how we’re going to report them.”

For now, positivity rate — the number of confirmed positive cases divided by the total number of tests conducted nationwide and at the local level — is the primary metric public health officials use to measure the nation’s testing capacity.

Last week, the average U.S. positivity rate was 6.3%, according to Johns Hopkins University. That’s higher than the 5% threshold set by the World Health Organization for easing quarantine restrictions. The more cases per capita, the more testing is needed to determine the true level of infection. And since the virus is spreading out of control in many states, the need for more testing is spiraling.

In early August, the United States was performing roughly 750,000 laboratory-based tests per day, with an average time to results of more than four days. “I don’t care how many tests we’re patting ourselves on the back for,” Nuzzo said. “They’re meaningless if the results take more than two days.”

As of last week, the average number of U.S. laboratory-based tests per day had fallen to about 675,000, although the total number of those tests is expected to increase slightly in the weeks ahead.

Scott Becker, CEO of the Association of Public Health Laboratories, said the labs that test the samples are operating at maximum capacity around the clock but are limited by constant shortages of reagents, swabs and other supplies.

As a result, increasingly popular and plentiful antigen tests are starting to make up a larger share of total testing. That means that positivity rates could become meaningless if users of antigen tests don’t start reporting their results to state and local health agencies.

“We know that millions of these tests have been conducted, but they’re not showing up in state data,” Madrigal said. “A lot of information may be lost at the point of care and not reported. Those [rapid-results] devices don’t have Bluetooth or any kind of connection. It’s also possible that states are sitting on antigen test data and not willing to publish it.”

Expanding Capacity

In addition to tests potentially going unreported, some national experts question whether the industry will be able to produce enough of the antigen kits to meet the country’s skyrocketing demand.

The device used to test DeWine was made by diagnostics company Quidel, which received emergency authorization from the FDA in May. Beckton Dickinson, or BD, which received FDA authorization in July for a similar device, is the only other maker. Both companies also make quick, point-of-care tests for strep throat, flu and other infectious diseases.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services last week invoked the Defense Production Act to prioritize federal purchases of the tests for use in nursing homes nationwide. That follows an announcement in July that the agency was shipping hundreds of thousands of tests or test kits to nursing homes, starting with those in COVID-19 hotspots.

Meanwhile, the National Institutes of Health has invested roughly $250 million in research aimed at developing other technologies to boost the nation’s rapid testing capacity.

In approving a saliva-based test last week, the FDA said the new testing technique developed by Yale School of Public Health could substantially reduce shortages of the laboratory supplies need to expand capacity.

“Providing this type of flexibility for processing saliva samples to test for COVID-19 infection is groundbreaking in terms of efficiency and avoiding shortages of crucial test components like reagents,” said FDA Commissioner Dr. Stephen M. Hahn.

Screening vs. Diagnostic

DeWine’s erroneous test result this month was significant because he was among six governors who had announced a compact to buy 3.5 million antigen test kits for use in their states.

The compact, supported by The Rockefeller Foundation, has since grown to 10 states and a larger number of kits, and it’s expected to expand in the weeks ahead, according to Eileen O’Connor, the foundation’s senior vice president of communications, policy and advocacy.

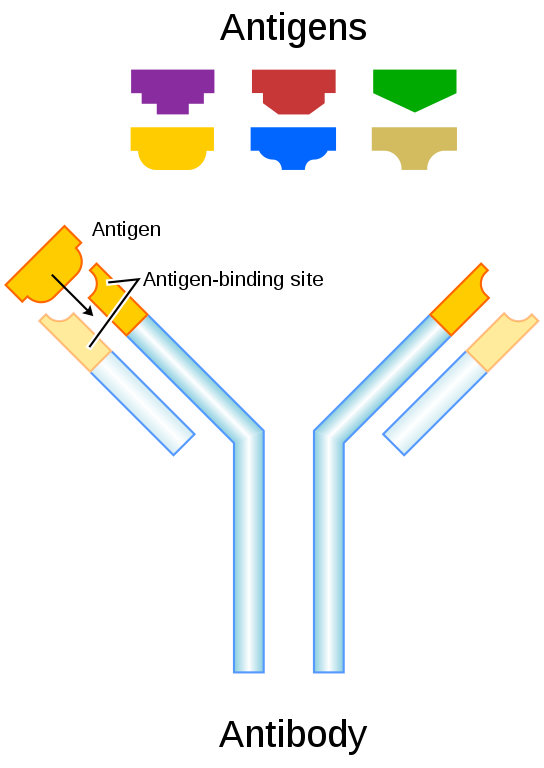

But it turns out that the Ohio governor was not a good candidate for the antigen test he received. Both Quidel and BD specify that their antigen tests are for diagnostic purposes only and should not be used on people without COVID-19 symptoms.

DeWine had no symptoms and no reason to believe he’d been exposed to the virus. Still, White House protocol required him to produce a negative COVID-19 test before meeting with the president, and no other test could deliver results quickly enough.

At least 40% of people infected with COVID-19 have no symptoms, and those who do have symptoms are contagious for at least four days before symptoms occur. That’s why a fast, reliable test for screening people with no symptoms is crucial.

Quidel reports its test has a sensitivity rate of 97%, meaning it detects the virus in 97% of people infected with it once they exhibit symptoms. That’s on par with the laboratory tests most people are receiving now. BD claims a sensitivity rate of 84%.

But when used on asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic people as a screening tool, the average error rate is at least 20%. False positive results like the one DeWine received are rare. Antigen tests are much more likely to produce false negatives, because they lack the sensitivity to pick up trace amounts of the protein component of the virus in asymptomatic people.

Mara Aspinall, a professor of biomedical diagnostics at Arizona State University, speculated that the Ohio governor’s false test was the result of user error, contamination or a faulty test kit.

A similar problem cropped up at a clinic in a small town in Vermont, where 65 people tested positive using an antigen test, and 48 of them ended up testing negative using a laboratory test.

Still, Aspinall and a growing number of other COVID-19 experts argue that rapid result testing may be the nation’s best shot at controlling the virus.

Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Read Stateline coverage of the latest state action on coronavirus.