Illustration: Stephanie King

By Kara Gavin, University of Michigan Health Lab

A deadly virus killed hundreds of thousands of Americans in just a few months.

Health officials made rules to stop its spread, but those rules varied widely across the country.

Many people wore masks to block the tiny killer — but not everyone.

It worked for a while, but the number of cases kept rising.

And hundreds of thousands more people died.

The story of 2020? No – that’s the story of the 1918-1919 flu pandemic in a nutshell.

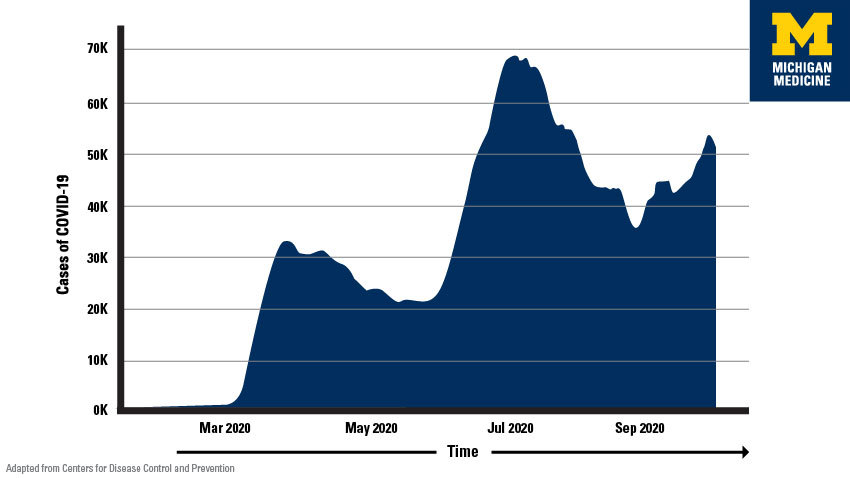

But now history seems to be repeating itself with the coronavirus. After “flattening the curve” of cases in late spring and again in late summer, cases of COVID-19 have surged in October.

Howard Markel, M.D., Ph.D., for one, is deeply dismayed – but not surprised.

He’s a medical historian at the University of Michigan whose team’s in-depth study of the 1918 flu led him to co-invent to the phrase “flatten the curve.” The team’s findings helped influence this year’s global effort to fight the coronavirus through masks, physical distancing and rules about certain types of gatherings, and business and entertainment activities.

“I really do fear that, between COVID-19 and the regular seasonal flu, this coming winter and spring could be as bad as, or worse than, what we saw in the horrible spring of 2020,” he says.

But we’re not doomed to repeat the fiasco of 102 years ago, he says.

In the end, his team’s research showed, fewer people perished, and the economy came back strongest, in the places that acted fast when cases rose, and didn’t let up too early on virus-stopping rules. And the world is a very different place than it was in 1918.

What happened? And what can we do?

“What has brought about this new ‘wave’ is that more and more people have been putting themselves in situations where they can be exposed to the virus, without masks, because of pandemic fatigue,” Markel says. “The virus never stopped circulating, we have just come out of hiding. Which means this isn’t over, and the threat is still there.”

How people behave during the coming holidays – from Halloween to New Year’s Day – could play a big role in how much havoc the virus will wreak over the next six months, he says. Colder weather is already sending people in Northern states indoors where the virus can spread more easily.

“Gathering with extended family members, and trusting them more than we trust others, is a normal human response – but it’s not a microbiologically informed response,” he explains.

After all, if they haven’t been wearing a mask in public or staying away from crowds, your favorite aunt or cousin could bring the virus to the Thanksgiving feast or football tailgate along with the pie or beer.

And the last holiday “gift” you want to give your grandfather or brother is a case of COVID-19.

So, it’s important to keep up the effort to keep gatherings small and outdoors if possible, avoid travel to and from areas with high numbers of cases, wear masks in public and stay home as much as possible.

Gatherings that involve alcohol – whether in a bar or a party – are especially risky, because drinking reduces inhibitions and decision-making. And having to speak up to be heard over loud groups or music means droplets can fly farther.

Does flattening the curve matter anymore?

The whole point of the ‘flattening the curve’ effort is to buy time for scientists, medical professionals, public health experts and pharmaceutical companies to do what they do best: Learn how to keep people from getting sick or dying, including developing vaccines and testing new treatments in rigorous studies.

It’s also meant to keep hospitals from getting so overwhelmed with severely ill patients that they can’t provide the best care to everyone – and that they have to cut back on regular care for the rest of their patients.

And keeping cases to a low level means that contact tracers can find people who might have been exposed to a sick person when they were contagious, and help them get tested and quarantined away from others.

Markel notes that the advantage we have over 1918 is that we have a lot more scientific firepower to aim at the virus, which in just 9 months has revealed a lot. We also have the ability for many people to work, learn, see their health providers, order food, get entertainment and interact socially over the Internet.

SEE ALSO: Flattening the Curve for COVID-19: What Does It Mean and How Can You Help?

The fact that deaths have not surged in the past few months, even as cases have surged, is evidence that this is actually working. Even though medical teams don’t yet have a “magic bullet” drug to use against the virus, they know much more about how to treat patients and have access to experimental options.

“We now know that your risk of catching coronavirus boils down to the three D’s – duration of exposure, distance from others and the diverse number of people you’re exposed to.”

Howard Markel, M.D., Ph.D.

But that means we also need to follow the science about prevention, Markel says. We now know that the virus spreads mostly through air, especially indoors; that people can spread it for days before they develop symptoms; that anyone of any age can catch and spread it; and that certain factors make someone more likely to develop a serious case or die.

“We now know that your risk of catching coronavirus boils down to the three D’s – duration of exposure, distance from others and the diverse number of people you’re exposed to,” he explains.

The fact that the number of cases at schools, colleges and universities hasn’t been worse, in many cases, is a testament to those institutions’ efforts. But what students do in their spare time can drive the virus to spread.

What about herd immunity?

By now, about one in eight Americans has been infected with the coronavirus, including the 8 million who have tested positive and millions more who are estimated to have had it before testing was widely available.

This has led some politicians, commentators and everyday people to say that we should just “let it rip” by removing preventive practices and allowing the virus to spread among most people while shielding the elderly and immune-compromised.

Their goal: restoring economic activity by achieving a ‘herd immunity’ similar to what happens when the vast majority of the population is vaccinated against a disease.

This isn’t just beyond stupid, it’s dead wrong, says Markel.

“The whole advantage of living in the 21st Century compared with the Middle Ages or even 1918 is that we can apply science to a public health crisis,” he says. “Why would anyone want to catch this disease if they don’t have to, given that we still don’t understand exactly what makes someone get a serious case, and we now know that it can cause long-lasting symptoms?”

“Letting it rip” could mean millions of deaths, an overwhelmed medical system that won’t be able to take care of people, and massive lost worker productivity and economic activity too.

“The idea that we can just get over this and move on, without an effective vaccine, is short-sighted and dangerous,” he says. “For businesses, the smartest thing is to keep your customer base as healthy as possible. For governments, supporting those people and business sectors that have suffered the most economically makes much more sense. And for individuals, the immune system is much more likely to create a lasting resistance to the virus when given a vaccine, not from getting sick.”

In other words, he says, “Now is not the time to give up. If we are lax we will fatten the curve, not flatten it. The humane, ethical, scientifically based and smart thing to do is to wait this out until we have a vaccine.”