COVID stress syndrome: 5 ways the pandemic is affecting mental health

Gordon J. G. Asmundson, University of Regina

In addition to its staggering impact on physical well-being and mortality, COVID-19 is also taking an unprecedented toll on our mental health. Numerous recent studies have shown global increases in the prevalence and severity of depression and anxiety as well as increases in post-traumatic stress disorder and substance abuse.

These increases likely stem from the changes to daily life we have all been asked to make in attempts to mitigate viral spread.

Yet conventional mental health approaches and diagnoses do not fully capture the nuanced mental health impacts of this pandemic. These approaches may not be sufficient to guide the development of strategies to address the pandemic’s rapidly increasing mental health burden.

As clinical psychologists with expertise in fear and anxiety-related conditions as well as assessment and treatment development, our team was interested in trying to fully understand the specific mental health effects of this pandemic in order to inform the development of effective public health messaging and evidence-based interventions.

Supported by funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the University of Regina, we conducted a longitudinal population-based survey of a large sample of Canadian and American respondents, with surveys administered in late March, mid-May and early July of 2020. Based on this data we determined that the mental health impact of COVID-19 is best understood as a multi-faceted syndrome comprising a network of interconnected symptoms.

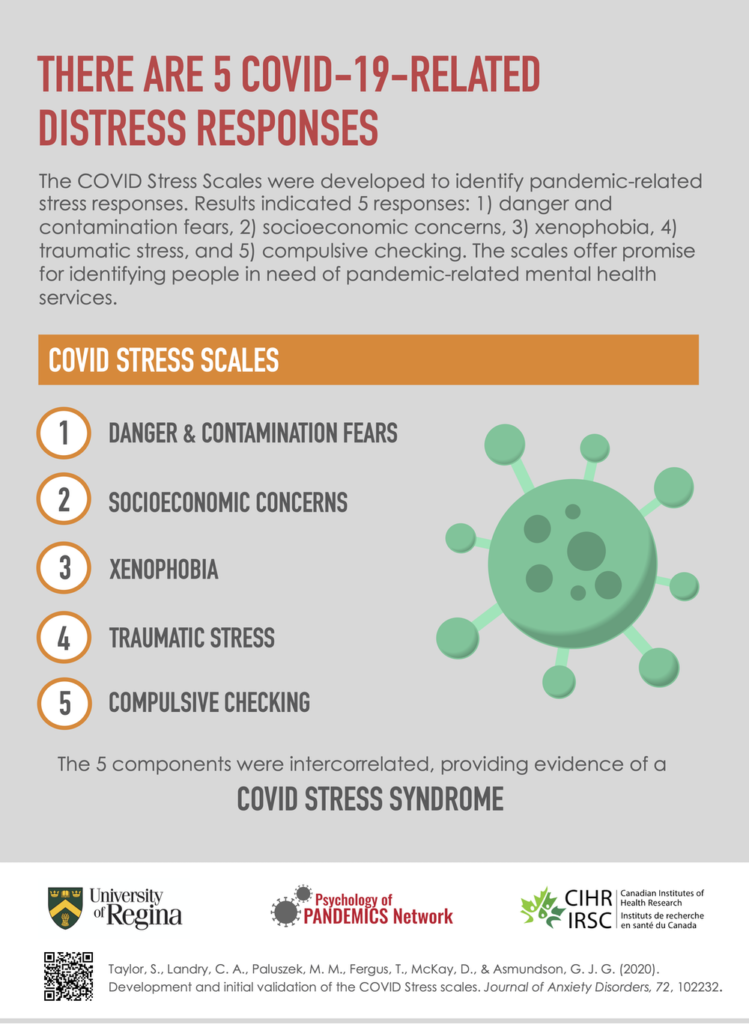

COVID Stress Scales

Using data from approximately 7,000 respondents collected in late March, we developed, validated and published our COVID Stress Scales. These scales assess five core features of COVID-19-related stress: fear of danger and contamination, fear of adverse socio-economic consequences, checking and reassurance seeking, xenophobia (discrimination against foreigners) and traumatic stress symptoms (for example, pandemic-related nightmares).

Since the five scales were intercorrelated, they can also be added together to provide an overall indication of pandemic-related stress levels.

The COVID Stress Scales, now translated into 12 languages, offer widespread promise as a tool for better understanding the distress associated with COVID-19 and for identifying people in need of mental health services. An online self-assessment that provides people with a severity rating and self-help recommendations is now available.

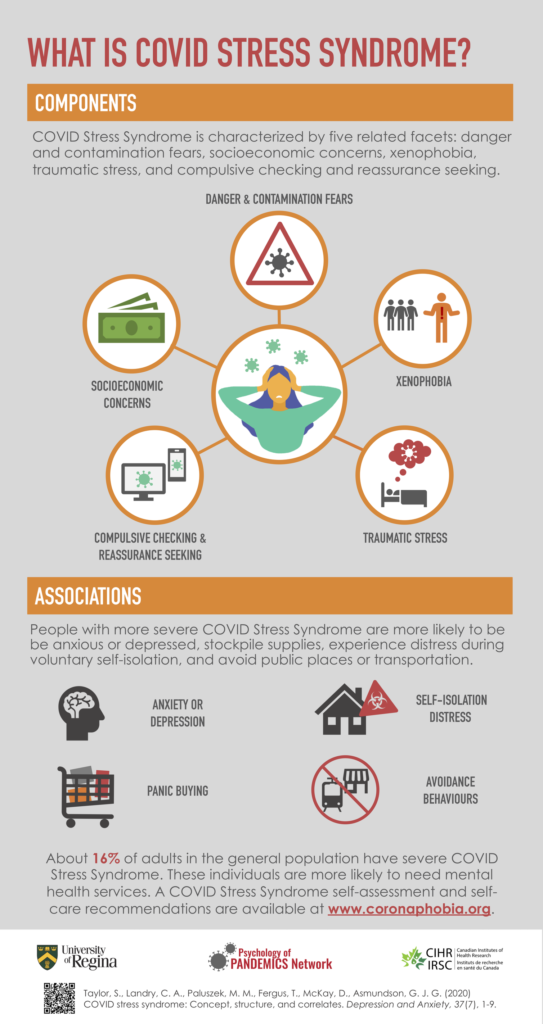

COVID stress syndrome

The five COVID Stress Scales are intercorrelated; that is, the symptoms measured by each of the five scales tend to occur together. This observation provided initial evidence that the various symptoms of COVID-19-related distress may be facets of a syndrome. We further evaluated and confirmed this idea in a subsequent study.

The COVID stress syndrome is anchored by COVID-19-related danger and contamination fears as its central feature, with strongest connections to fear of adverse socio-economic consequences and disease-related xenophobia (fear of foreigners who might be carrying infection).

Fear of adverse socio-economic consequences was the second-most central feature, highlighting the importance of impacts of the pandemic on social and financial security.

Traumatic stress symptoms were the third-most central feature and most strongly associated with danger and contamination fears and checking and reassurance seeking, suggesting a vicious cycle wherein these facets of the syndrome fuel each other. For example, more exposure to COVID-19 news or social media may lead to greater frequency of nightmares about COVID-19, which, in turn, increases fear of contamination and further fuels checking the news and social media for up-to-date information.

Although less central, xenophobia affected fears of danger and contamination, socio-economic consequences and, to a lesser extent, checking and reassurance seeking, highlighting the impact of discriminatory beliefs on pandemic-related emotional responding.

Substantial mental health footprint

Our preliminary findings suggest the percentage of the population affected by COVID stress syndrome is substantial, with the mental health footprint of COVID-19 exceeding the medical footprint. Although two per cent of our sample reported having had COVID-19 and six per cent knew someone who had been infected, 38 per cent and 16 per cent respectively were classified as having moderate-to-severe or severe COVID-19-related distress.

In short, more than 50 per cent of the population reported considerably elevated levels of distress specific to the pandemic. Higher scores were associated with things like panic buying, excessive avoidance of public places and unhelpful ways of coping (for example, overeating and overusing drugs and alcohol) during self‐isolation.

In subsequent studies we have shown that elevated COVID stress is also associated with greater stigmatization of health-care workers and that the significant proportion of the population with pre-existing anxiety disorders experience more negative effects than those with depressive disorders or no mental health conditions.

On a positive note, we have also observed that elevated COVID stress is associated with favourable attitudes towards vaccination, use of personal protective equipment and pandemic-related altruism.

Looking forward

Our research has identified what appears to be a network of interconnected symptoms, a COVID stress syndrome, with fear of the dangerousness of the SARS-CoV-2 virus at the core, interconnecting to socio-economic concerns, xenophobia, traumatic stress symptoms and compulsive checking and reassurance seeking. The syndrome, in turn, is primarily associated with other negative mental health and socially disruptive consequences such as panic buying, excessive avoidance and unhelpful ways of coping during self‐isolation.

We anticipate that as the COVID-19 pandemic evolves, so too will the mental health challenges and needs of the public. Further research is needed to understand the full effects of COVID-related stress and whether these change as the pandemic progresses.

Research is also needed to understand the disruptive impact of the antithesis of COVID-19 stress, that being a disregard for the seriousness of COVID-19 and its consequences.

COVID-19 has generated a complex network of mental health reactions. The concept of the COVID stress syndrome can help build the nuanced understanding of those reactions necessary to develop targeted, evidence-based campaigns and interventions to reduce its psychological footprint. These developments are as critical to reducing the mental health toll of the pandemic as is the discovery of a vaccine to facilitating immunity.

Gordon J. G. Asmundson, Professor of Psychology, University of Regina

COVID stress syndrome: 5 ways the pandemic is affecting mental health

Gordon J. G. Asmundson, University of Regina

In addition to its staggering impact on physical well-being and mortality, COVID-19 is also taking an unprecedented toll on our mental health. Numerous recent studies have shown global increases in the prevalence and severity of depression and anxiety as well as increases in post-traumatic stress disorder and substance abuse. These increases likely stem from the changes to daily life we have all been asked to make in attempts to mitigate viral spread.

Yet conventional mental health approaches and diagnoses do not fully capture the nuanced mental health impacts of this pandemic. These approaches may not be sufficient to guide the development of strategies to address the pandemic’s rapidly increasing mental health burden.

As clinical psychologists with expertise in fear and anxiety-related conditions as well as assessment and treatment development, our team was interested in trying to fully understand the specific mental health effects of this pandemic in order to inform the development of effective public health messaging and evidence-based interventions.

Supported by funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the University of Regina, we conducted a longitudinal population-based survey of a large sample of Canadian and American respondents, with surveys administered in late March, mid-May and early July of 2020. Based on this data we determined that the mental health impact of COVID-19 is best understood as a multi-faceted syndrome comprising a network of interconnected symptoms.

COVID Stress Scales

Using data from approximately 7,000 respondents collected in late March, we developed, validated and published our COVID Stress Scales. These scales assess five core features of COVID-19-related stress: fear of danger and contamination, fear of adverse socio-economic consequences, checking and reassurance seeking, xenophobia (discrimination against foreigners) and traumatic stress symptoms (for example, pandemic-related nightmares).

Since the five scales were intercorrelated, they can also be added together to provide an overall indication of pandemic-related stress levels.

The COVID Stress Scales, now translated into 12 languages, offer widespread promise as a tool for better understanding the distress associated with COVID-19 and for identifying people in need of mental health services. An online self-assessment that provides people with a severity rating and self-help recommendations is now available.

COVID stress syndrome

The five COVID Stress Scales are intercorrelated; that is, the symptoms measured by each of the five scales tend to occur together. This observation provided initial evidence that the various symptoms of COVID-19-related distress may be facets of a syndrome. We further evaluated and confirmed this idea in a subsequent study.

The COVID stress syndrome is anchored by COVID-19-related danger and contamination fears as its central feature, with strongest connections to fear of adverse socio-economic consequences and disease-related xenophobia (fear of foreigners who might be carrying infection).

Fear of adverse socio-economic consequences was the second-most central feature, highlighting the importance of impacts of the pandemic on social and financial security.

Traumatic stress symptoms were the third-most central feature and most strongly associated with danger and contamination fears and checking and reassurance seeking, suggesting a vicious cycle wherein these facets of the syndrome fuel each other. For example, more exposure to COVID-19 news or social media may lead to greater frequency of nightmares about COVID-19, which, in turn, increases fear of contamination and further fuels checking the news and social media for up-to-date information.

Although less central, xenophobia affected fears of danger and contamination, socio-economic consequences and, to a lesser extent, checking and reassurance seeking, highlighting the impact of discriminatory beliefs on pandemic-related emotional responding.

Substantial mental health footprint

Our preliminary findings suggest the percentage of the population affected by COVID stress syndrome is substantial, with the mental health footprint of COVID-19 exceeding the medical footprint. Although two per cent of our sample reported having had COVID-19 and six per cent knew someone who had been infected, 38 per cent and 16 per cent respectively were classified as having moderate-to-severe or severe COVID-19-related distress.

In short, more than 50 per cent of the population reported considerably elevated levels of distress specific to the pandemic. Higher scores were associated with things like panic buying, excessive avoidance of public places and unhelpful ways of coping (for example, overeating and overusing drugs and alcohol) during self‐isolation.

In subsequent studies we have shown that elevated COVID stress is also associated with greater stigmatization of health-care workers and that the significant proportion of the population with pre-existing anxiety disorders experience more negative effects than those with depressive disorders or no mental health conditions.

On a positive note, we have also observed that elevated COVID stress is associated with favourable attitudes towards vaccination, use of personal protective equipment and pandemic-related altruism.

Looking forward

Our research has identified what appears to be a network of interconnected symptoms, a COVID stress syndrome, with fear of the dangerousness of the SARS-CoV-2 virus at the core, interconnecting to socio-economic concerns, xenophobia, traumatic stress symptoms and compulsive checking and reassurance seeking. The syndrome, in turn, is primarily associated with other negative mental health and socially disruptive consequences such as panic buying, excessive avoidance and unhelpful ways of coping during self‐isolation.

We anticipate that as the COVID-19 pandemic evolves, so too will the mental health challenges and needs of the public. Further research is needed to understand the full effects of COVID-related stress and whether these change as the pandemic progresses.

Research is also needed to understand the disruptive impact of the antithesis of COVID-19 stress, that being a disregard for the seriousness of COVID-19 and its consequences.

COVID-19 has generated a complex network of mental health reactions. The concept of the COVID stress syndrome can help build the nuanced understanding of those reactions necessary to develop targeted, evidence-based campaigns and interventions to reduce its psychological footprint. These developments are as critical to reducing the mental health toll of the pandemic as is the discovery of a vaccine to facilitating immunity.

Gordon J. G. Asmundson, Professor of Psychology, University of Regina

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.