Ian Jacobs, University of New South Wales, Australia

My colleages’ and my efforts to develop a screening test for the early detection of ovarian cancer capable of saving lives arrived at a sad moment last week. The final trial results of the research I’ve focused on for 36 years, published in The Lancet, found early ovarian cancer detection doesn’t save lives.

The advances we have seen in science and technology over the past three decades have been nothing short of phenomenal. Each smartphone has more computational power than NASA had at its disposal during the moon landings. In medicine, researchers have sequenced the human genome, created life-saving treatment for HIV and rapidly developed vaccines for COVID-19.

There have been significant improvements in ovarian cancer treatment involving surgery and chemotherapy, but the sad and frustrating truth is of the four women diagnosed with ovarian cancer in Australia each day, three will eventually die from the disease.

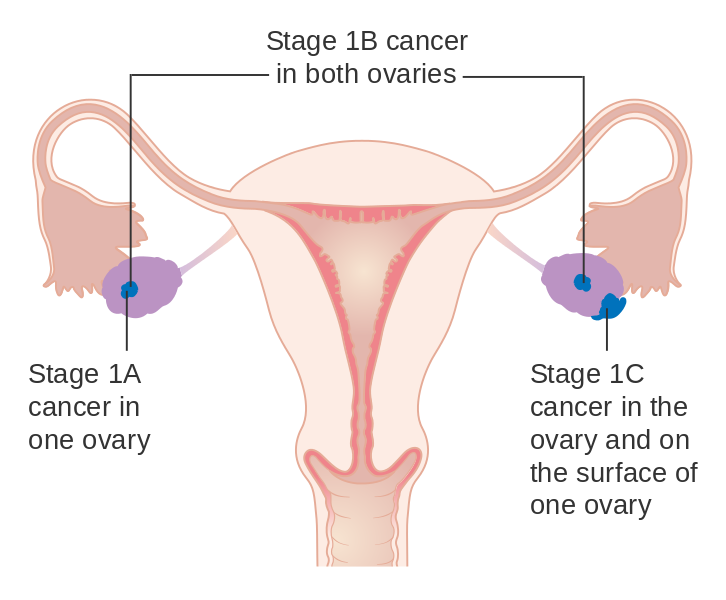

The diagnosis of ovarian cancer is dependent on women reporting symptoms to their doctor. However, few develop symptoms until they have advanced stage cancer, by which time the outlook is poor. Of all women’s cancers, ovarian cancer has the lowest survival rate, with just 46% of patients in Australia surviving five years. For breast cancer, it’s now 91%.

Back in the 80s

I was motivated to improve the outcome for women with ovarian cancer by my experience as a junior doctor in London in 1985. I was training with a brilliant surgeon who undertook operations for many women with ovarian cancer. In spite of the exhaustive surgery and the chemotherapy that followed, we saw far too many women suffer and die from ovarian cancer.

That experience inspired me to initiate a program of research designed to find a screening test to detect this cancer early. Women with the earliest stage of ovarian cancer had survival rates of 70%, but less than 20% of women with ovarian cancer were diagnosed that early.

My hypothesis was that if we could detect more cancers at an early stage it would save lives.

Based on evidence from other cancers, there was reason to be hopeful and two potential tests were available – a blood test called CA 125 and the use of ultrasound scanning which was then widely used in obstetrics.

Over the next 15 years, working with colleagues in the United Kingdom and United States, I developed and refined the screening tests and had great hope for what we called “multimodal screening”. This involved a “risk of ovarian cancer algorithm” for interpreting the change in blood levels of CA 125 over time to identify women who had a rising pattern, indicating an elevated risk of ovarian cancer. Women with an elevated risk could then have a secondary test involving ultrasound scanning.

During those 15 years, we published convincing evidence in studies involving over 50,000 women that this approach to screening was safe, acceptable to women, could detect over 85% of the cancers early and would probably be cost effective if sufficient lives were saved.

Promising early results

Before advocating screening of the general population, a massive trial would be needed to determine whether the screening would actually save lives.

The trial needed to involve screening and follow up of approximately 200,000 women for around 20 years. This would eventually include 2,000 women with ovarian cancer – enough to determine whether or not screening saved lives.

Work got underway in the United Kingdom in 2000 and optimism grew as initial results confirmed the ability of multimodal screening to detect cancer early in over 85% of cases.

By 2015, the preliminary mortality data were available and were tantalising. The curves hinted at a 20% or more reduction in deaths from ovarian cancer, but the findings did not quite reach statistical significance. So another five years of painstaking follow up was needed.

Disappointing final results

The final results of the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening showed the multimodal screening approach could detect cancers early and increase the number of early-stage ovarian cancers by almost 50%.

But to our surprise and despair, that did not reduce the number of deaths from ovarian cancer. All it seemed to do was to bring forward the time of diagnosis of the cancers in these women, without improving their survival.

This is deeply disappointing. Disappointing of course for those who like myself have dedicated much of their professional lives to this effort, but much more importantly for the women across the world who we had hoped would have access to an effective screening test able to save lives.

The hope had been to deploy ovarian cancer screening for women in the general population alongside breast and cervical cancer screening, but that will not happen – for a while at least.

Why didn’t early detection save lives?

To answer that, we need to further analyse samples and data from the trial. Our suspicion is that the women whose cancers were detected early by screening had more aggressive cancers than those (the 10%) whose cancers were detected early without screening, on the basis of symptoms.

So even with early detection, their cancers progressed relentlessly despite them receiving the best available surgery and chemotherapy.

If that is the case, we are likely to require screening tests which can detect ovarian cancer even earlier than our algorithm, which we estimate picks up ovarian cancer 18 to 24 months early. Saving lives may require a test capable of picking up the cancers five or more years early.

Read more: Why we need to pay more attention to negative clinical trials

Fortunately, there are exciting avenues of research involving advances in protein and DNA technologies which researchers in Australia and around the world are exploring. So there is hope.

But realistically, given the five-plus years needed to develop better screening tests and the ten to 15-plus years needed to have enough cases to conduct another large randomised trial, the solution is likely to be more than 20 years away.

Still, we’ve learnt a lot

This massive commitment of expertise, time, energy and funding has most definitely not been wasted. Much has been achieved along the way in this 36-year journey in developing ways to assess risk, diagnose cancer and prevent ovarian cancer which are now used in clinical practice.

New generations of researchers have been trained. The data and the blood bank collected is available to all researchers seeking new and better screening tests and is a unique resource. And the ability to detect ovarian cancer early may be invaluable in assessing new treatments.

I feel privileged to have led this effort and will always be grateful to the collaborators, researchers, health professionals, funding agencies and above all the 200,000 women who took part in the trial.

I feel a deep sadness that lives will not yet be saved by ovarian cancer screening, but I’m confident the next generation of researchers will build on our work and find approaches to screening and treatment of ovarian cancer which dramatically reduce the loss and suffering caused by this insidious disease.

Ian Jacobs, President and Vice-Chancellor, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Read the original article.