By Donna Kallner, The Daily Yonder

September 20, 2024

When my friend Lynn was instructed to produce a 24-hour urine collection for analysis, the materials were provided in a discreet tote bag with clear instructions about what to save (everything) and how to store it (chilled).

What the instructions didn’t address was how to manage a collection, if necessary, at a highway rest stop or gas station during the 3-½ hour drive to where she was scheduled to undergo a battery of tests that required good hydration.

So we did what many rural women do when they really, really need to pee: She crossed her legs and I pushed the speed limit.

Lynn has multiple myeloma, a blood cancer in which overgrowth of plasma cells in the bone marrow can crowd out normal blood-forming cells. The disease was detected early and smoldered for a while before a lesion appeared in an MRI ordered for another concern. That’s when she and her hematologist-oncologist decided on a course of treatment that would eventually lead to a stem cell transplant. And that would involve commuting to a regional cancer center several hours away.

If you come from a rural area, you probably know someone who has had to make that kind of commute for treatment. Who has weighed the cost of gas, food and lodging away from home. Who has learned the back ways around a strange city to avoid road construction or rush hour congestion. Who packed an extra week’s worth of clothes, just in case.

Lynn’s cancer commute started closer to home with a course of chemotherapy treatments just 25 miles away. Her family lives too far away for it to be practical for them to drive her to appointments. So her initial plan was to just drive herself. But some early side effects convinced her to let friends in our rural community help.

When it came time for her cancer commute to include trips downstate, we had developed a pattern: Having someone else drive and make notes during medical appointments let her conserve her energy for research about the disease, asking important questions, studying options for treatment, managing medications, and making decisions about how to manage her life during and after treatment.

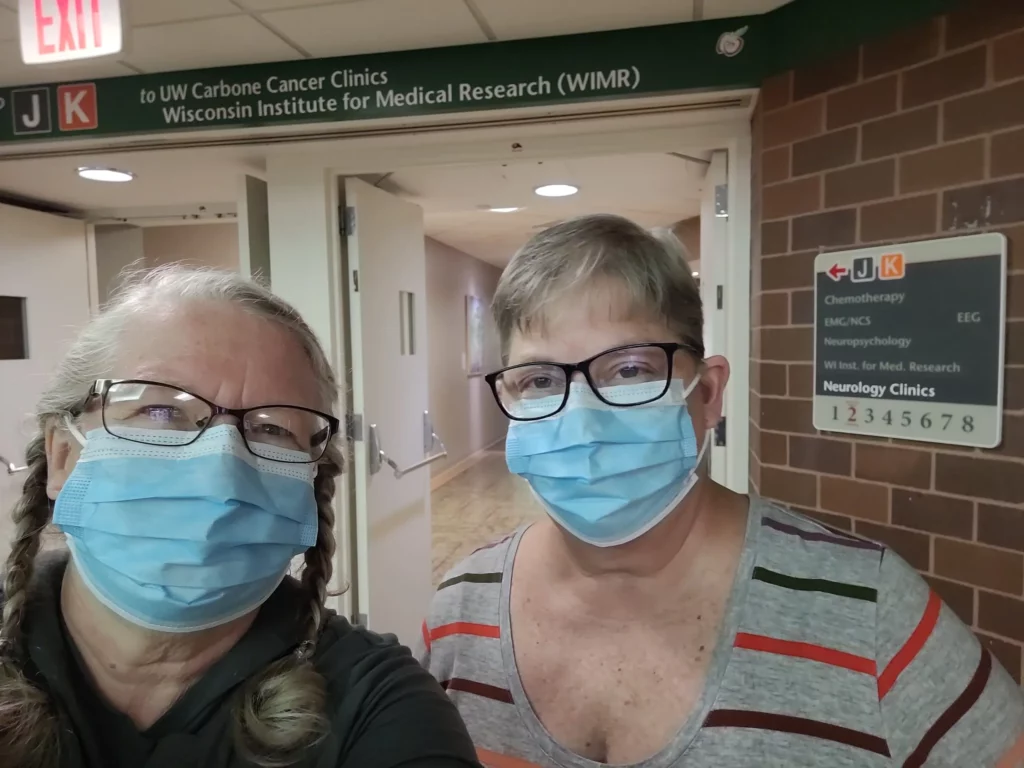

Our first trip to Madison was a down-and-back in one day to meet with the transplant hematologist-oncologist. We also met the nurse navigator who has since scheduled appointments and coordinated with multiple departments to ensure things happen when they are supposed to. She even coordinated our housing on subsequent trips – making reservations at a hotel near the hospital that provides shuttle service to the hospital and managing whatever paperwork was necessary to have grants pick up the tab for our housing. Other out-of-pocket expenses add up enough, but removing lodging from the tally is huge.

Our next trip downstate was for the harvest of stem cells. Lynn was to have an autologous transplant of her own cells. So before the trip, she self-administered a series of white blood cell growth factor injections to help release stem cells from the bone marrow into the bloodstream. We drove back to Madison for additional injections the night before the harvest of peripheral stem cells from her blood.

That harvest was an outpatient procedure. Upon our arrival early that morning, Lynn had lines inserted into both arms. From a vein in one arm, blood flowed into a centrifuge where stem cells were separated out. The rest of the blood was returned via a vein in the other arm. The entire procedure takes several hours.

Like many medical procedures, stem cell collection goes more smoothly when the patient is well-hydrated. So during our drive the previous day and overnight, Lynn was trying to time her fluid intake to achieve a good level of hydration – but one that wouldn’t require use of a bedpan during the procedure. She had her legs crossed at the end but managed to wait for her nurse to remove the needles before sprinting for the bathroom.

We stayed another night in Madison on that trip. We were prepared to go back to the hospital for an additional harvest, if necessary. It took several hours to get lab results but the verdict was she had produced the desired amount of stem cells for her transplant and a second transplant if needed.

Back at home, Lynn did another course of chemo locally before we returned to Madison for a battery of pre-transplant tests.

Because we were coming from a distance, the nurse navigator scheduled all of those outpatient tests in a single day. Again, she arranged local housing for us the night before and so we wouldn’t have to drive home after a long day of back-to-back appointments.

The first appointment was at the lab for blood work and to deliver the results of that 24-hour urine collection. From there Lynn moved on to pulmonary function tests, echocardiogram and EKG, and another sedated bone marrow biopsy. After a series of CT scans at another nearby facility, we rested up for the drive home the next day.

Our next trip down was for the consent conference with the transplant hematologist-oncologist. There were additional meetings with the nurse navigator and a pharmacist, and for Lynn’s final labs and nasal swab to make sure she was healthy enough to proceed. We came home for two nights, then returned prepared for Lynn’s transplant and inpatient stay.

Before she was admitted, Lynn and I returned to now-familiar lodgings near the hospital for a three-night stay. The next morning we reported to the hospital for two outpatient procedures. First, a PICC line was inserted in her arm. That would provide intravenous access for blood draws and IV fluids.

The first thing it was used for, though, was administration of one last, powerful blast of chemotherapy to kill any remaining cancer cells and to suppress the immune system to decrease the risk of her body rejecting the transplant. Lynn chewed ice chips before and throughout that chemo to constrict blood vessels in the mouth and throat to minimize the mouth sores associated with that chemo.

Afterward, we returned to the hotel to rest while the chemo did its work and cleared her system. The anti-nausea drugs worked very well for Lynn during that time and she was able to eat and drink. We played cribbage, watched movies, read and rested. Except for room service, it was a little like deep winter at home Up North.

Two days later, we checked out of the hotel and she checked into the hospital for an expected inpatient stay of two to three weeks. I was able to stay with her while she got the infusion of stem cells from the collection in July.

And then I left her there – with enough clothes for a 3-week stay because there wouldn’t be anyone nearby to pick up and do her personal laundry during her stay. She was prepared for nausea, constipation, diarrhea, fatigue, fever, blood transfusions, hair loss, boredom. She was prepared to miss her dog, who is living with my family until Lynn’s doctor says Molly can go home.

That won’t be for a while. Lynn can be discharged once she is free of fever and active infection, able to take medications by mouth, and able to eat and drink enough. Once the transplanted stem cells start making new cells in her bone marrow, the risk of bacterial infection will decrease. But until her brand spanking new immune system gets stronger, there’s a high risk of infection from exposure to viruses, fungus and molds. For the first six months after transplant, Lynn is to avoid close contact with people who may have infectious diseases (including elementary school-age grandchildren). She must avoid exposure to water sources like ponds and lakes, and to dust or airborne particles like those around farms.

Before her transplant, Lynn had the ductwork in her house cleaned and her HVAC system serviced. She cleaned her house from top to bottom. And when she should have been cleaning, she pulled weeds in her flower gardens. Because she won’t be able to touch soil, either, until her immune system gets stronger. So her houseplants, like her dog, are with my family for the time being.

Lynn also had her private well tested for both bacteria and nitrates. Both tests were fine, but she will be required to drink bottled water for a while before she’s allowed to drink tap water from her rural well.

Lynn’s friends are lined up to help her through the next phase of her recovery. They will be mowing her lawn and raking her leaves this fall. They will pick up her groceries in town until she feels up to driving. Before she starts driving, I understand they plan a deep cleaning of her car’s interior. She already had her car’s cabin air filter changed.

Friends will haul her trash to our rural transfer center and help clean her house even if we have to hogtie her (with all visitors required to wear masks, she won’t be able to ID her assailants, right?). They will bring her meals prepared according to strict guidelines from the hospital dietician, who we met via a Zoom conference well before her transplant. Because where we live, you can’t just Uber what you need from across town. So it’s best to prepare ahead of time, as much as you can.

We’re prepared for more trips to Madison after she comes home. Routine follow-up visits may be weekly at first, then at longer intervals. We’ll be packed and ready to go at a moment’s notice, though, if she experiences any of the conditions outlined in the patient guide. Eventually, instead of commuting downstate she will be able to get labs done closer to home.

There are people who have to travel farther when they’re sicker. We’ve met patients and family members from rural areas hunkered down at the hotel for longer stays, and seen others we suspect are in and out like we have been. Occasionally in the shuttle van we exchange hometowns during the short drive from hotel to hospital or back. It’s another kind of rural community – those away from home for the care they need but eager to get back.

Donna Kallner writes from Langlade County in rural northern Wisconsin, where she has learned that homegrown rhubarb may be effective against garden variety chemo constipation but not the cocktail of strong anti-nausea drugs given with melphalan. Oh, and you can buy gel-lined leak-resistant barf bags on Amazon.

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.