By Shalina Chatlani, Stateline

April 7, 2025

Republicans in Congress are eyeing $880 billion in cuts to Medicaid, the joint federal-state government health care program for lower-income people.

Depending on how states respond, a Republican proposal that would slash the 90% federal contribution to states’ expanded Medicaid programs would end coverage for as many as 20 million of the 72 million people on Medicaid — or cost states $626 billion over the next decade to keep them on the rolls. More than 5 million people could lose coverage if the feds impose work requirements.

In recent months, this complicated government program has increasingly come under the spotlight, so Stateline has put together a guide explaining what Medicaid is and how it operates.

1. Medicaid is not Medicare.

Medicaid serves people with lower incomes or who have a disability. Medicare focuses primarily on older people, no matter their income.

Medicaid and Medicare were created in 1965 under President Lyndon B. Johnson. Medicare is the federal health insurance program for people who are 65 or older, though younger people with special circumstances, such as permanent kidney failure or ALS, may be eligible earlier.

Medicare is a supplemental insurance program that’s limited in scope. It doesn’t pay for long-term care, most dental care or routine physical exams. Around 68.4 million people are enrolled in Medicare.

Medicaid is a more comprehensive government insurance plan that’s jointly funded by the federal government and states. Medicaid covers most nursing home care as well as home- and community-based long-term care. People on Medicaid generally don’t have any copayments. Only people and families with incomes under certain thresholds are eligible for Medicaid. About 72 million people, or a fifth of people living in the United States, receive Medicaid benefits.

2. Medicaid eligibility varies from state to state.

In its original form, Medicaid was generally only available to children and parents or caretakers of eligible children with household incomes below 100% of the federal poverty line ($32,150 for a family of four in 2025). Over the years, the program was expanded to include some pregnant women, older adults, blind people and people with disabilities.

More than 5M could lose Medicaid coverage if feds impose work requirements

States have to follow broad federal guidelines to receive federal funding. But they have significant flexibility in how they design and administer their programs, and they have different eligibility rules and offer varying benefits.

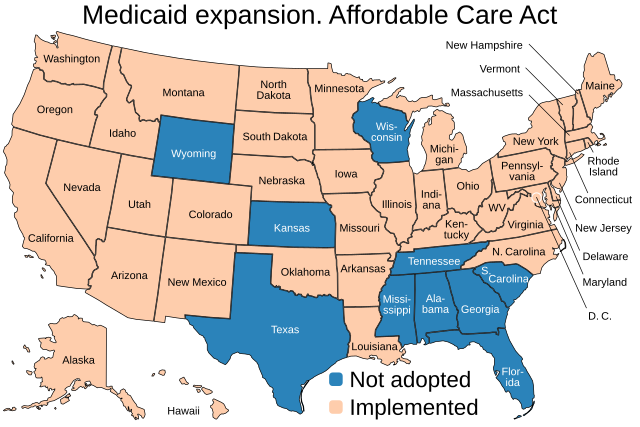

In 2010, President Barack Obama signed into law the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, which allowed states to expand their eligibility thresholds to cover adults with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty line (about $21,000 for one person today), in exchange for greater federal matching funds. The District of Columbia covers parents and caretakers who earn up to 221% of the federal poverty line.

Only 10 states (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin and Wyoming) have chosen not to expand coverage. In the non-expansion states, eligibility for caretakers and parents ranges from 15% of the federal poverty line in Texas to 105% in Tennessee. In Alabama, people can only get Medicaid if they earn at or below 18% of the federal poverty line — $4,678 a year for a three-person household.

3. Traditional Medicaid exists alongside a health insurance program for children called CHIP.

Low-income children have always been eligible for Medicaid. But in 1997, Congress created CHIP, or the Children’s Health Insurance Program. The law gave states an opportunity to draw down enhanced federal matching funds to extend Medicaid coverage to children within families who earn too much money to qualify for traditional Medicaid coverage, but make too little money to afford commercial health care.

Like Medicaid, CHIP is jointly funded by the federal government and states, but it’s not an entitlement program. CHIP is a block grant program, meaning states receive a fixed amount of federal money every year and aren’t obligated to cover everyone who meets the eligibility requirements. States get to decide, within broad federal guidelines, how their CHIP programs will work and what the income limits will be. Some states have chosen to keep their CHIP and Medicaid programs separate, while others have decided to combine them by using CHIP funds to expand Medicaid eligibility.

4. Medicaid and CHIP are significant portions of state budgets.

In 2024, the federal government spent less on Medicaid and CHIP than on Medicare, with Medicare spending accounting for 12%, or $847.5 billion, of the federal benefit budget, and Medicaid and CHIP accounting for 8%, or $584.5 billion.

But at the same time, Medicaid is the largest source of federal funds for states, accounting for about a third of state budgets, on average, and 57% of all federal funding the states received last year.

5. Federal funding varies by state.

Before the Affordable Care Act, federal Medicaid funding to states mostly depended on a formula known as the FMAP, or the federal medical assistance percentage, which is based on the average personal income of residents. States with lower average incomes get more financial assistance. For example, the federal government reimburses Mississippi, which is relatively poor, nearly $8 for every $10 it spends, for a net state cost of $2. But New York is only reimbursed $5. By law the FMAP can’t be less than 50%.

Medicaid cuts could hurt older adults who rely on home care, nursing homes

The ACA offered states the opportunity to expand eligibility and receive an even greater federal matching rate. In expansion states, the federal government covers 90% of costs for expansion adults. If Republicans in Congress reduce that percentage, states would have to use their own money to make up for lost federal dollars. They might have to scale back Medicaid coverage for some groups, eliminate optional benefits or reduce provider payment rates. Alternatively, they could raise taxes or make cuts in other large budget items, such as education.

Another possibility is that states that have adopted Medicaid expansion would reverse it. Nine states (Arizona, Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Montana, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Utah and Virginia) already have “trigger” laws in place that would automatically rescind expansion if the federal match rate dips below 90%. Other states are considering similar legislation.

One new analysis from KFF, a health research policy group, found that if Congress reduced the federal match for the expansion population to the percentages states get for the traditional Medicaid population — 50% for the wealthiest states and 77% for the poorest ones — it would cost states $626 billion over the next decade to keep everyone eligible under Medicaid expansion on the rolls.

6. Medicaid is the largest source of health coverage, especially for people with low incomes.

Medicaid is the single largest health payer in the nation, and is particularly important for people in poverty. Almost a fifth of people living in the United States are covered through Medicaid. But nearly half of all adults with incomes at or below the federal poverty line are insured through the program. Medicaid covers 4 out of every 10 children overall, but it covers 8 out of every 10 children below the federal poverty line. Medicaid also provides coverage for people experiencing homelessness or who are leaving incarceration.

7. Medicaid covers essential services, such as childbirth.

In exchange for receiving federal funds, states are obligated to cover essential health care services, including inpatient and outpatient hospital services, doctor visits, laboratory work and home health services, among other things. States get to decide which optional services, such as prescription drugs and physical therapy, they want to cover.

Medicaid is a significant payer of essential services. For example, the program covers 41% of all childbirths in the U.S. and covers health care services for the 40% of all adults ages 19-65 with HIV.

8. The majority of Medicaid spending goes to people with disabilities and to pay for long-term care.

ACA expansion adults — about 1 out of every 4 enrollees — accounted for 21% of total Medicaid expenditures in 2021. Children, who make up about 1 out of every 3 enrollees, only accounted for 14% of spending.

People who qualify for Medicaid because of a disability or because they are over the age of 65 make up about 1 out of every 4 enrollees. But they accounted for more than half of all Medicaid spending. That’s because these populations typically experience higher rates of chronic illness and require more complex medical care. Older people are also more likely to use nursing homes and other long-term care facilities, which can be expensive.

Cuts could also mean that older people relying on Medicaid for home-based care and long-term nursing home services could be significantly affected.

9. Some state Medicaid programs cover people who are living in the country illegally.

People who are in the country illegally are ineligible for traditional Medicaid or CHIP. But some states have carved out exceptions to extend coverage to them using state dollars.

As of January, 14 states and the District of Columbia provide Medicaid coverage to children regardless of their immigration status. And 23 states plus the District of Columbia use CHIP to cover pregnant enrollees regardless of their immigration status.

Also, seven states provide Medicaid to some adults who are here illegally. New York opted to cover those who meet the income requirements and are over the age of 65, regardless of immigration status And California provides coverage to any adults ages 19-65 who are under the income threshold, regardless of immigration status.

10. The majority of the public holds favorable views of Medicaid.

According to surveys from KFF, two-thirds of Americans say that someone close to them has received health coverage from Medicaid at some point in their lives. Half of the public also say they or someone in their family have been covered through Medicaid.

Generally, around 3 out of every 4 people — regardless of political party — say that Medicaid is very important, though Republicans are less likely than Democrats and independents to share that opinion. At the same time, a third or less of people want to see any decrease in spending on the Medicaid program. In fact, the majority of people living in states that have not expanded Medicaid under the ACA want their states to do so.

Stateline reporter Shalina Chatlani can be reached at schatlani@stateline.org.

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

SUPPORT

Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: info@stateline.org.