The Ground Game for Medicaid Expansion: ‘Socialism’ or a Benefit for All?

By Michael Ollove, Stateline

OMAHA, Neb. — On a sun-drenched, late October afternoon, Kate Wolfe and April Block are canvassing for votes in a well-tended block of homes where ghosts and zombies compete for lawn space with Cornhusker regalia. Block leads the way with her clipboard, and Wolfe trails behind, toting signs promoting Initiative 427, a ballot measure that, if passed, would expand Medicaid in this bright red state.

Approaching the next tidy house on their list, they spot a middle-aged woman with a bobbed haircut pacing in front of the garage with a cellphone to her ear.

Wolfe and Block pause, wondering if they should wait for the woman to finish her call, when she hails them. “Yes, I’m for Medicaid expansion,” she calls. “Put a sign up on my lawn if you want to.” Then she resumes her phone conversation.

Apart from one or two turndowns, this is the sort of warm welcome the canvassers experience this afternoon. Maybe that’s not so surprising even though this is a state President Donald Trump, an ardent opponent of “Obamacare,” or the Affordable Care Act, carried by 25 points two years ago.

Although there has been no public polling, even the speaker of the state’s unicameral legislature, Jim Scheer, one of 11 Republican state senators who signed an editorial last month opposing the initiative, said he is all but resigned to passage. “I believe it will pass fairly handily,” he told Stateline late last month.

Bills to expand eligibility for Medicaid, the health plan for the poor run jointly by the federal and state governments, have been introduced in the Nebraska legislature for six straight years. All failed. Senate opponents said the state couldn’t afford it. The federal government couldn’t be counted on to continue to fund its portion. Too many people were looking for a government handout.

Now, voters will decide for themselves.

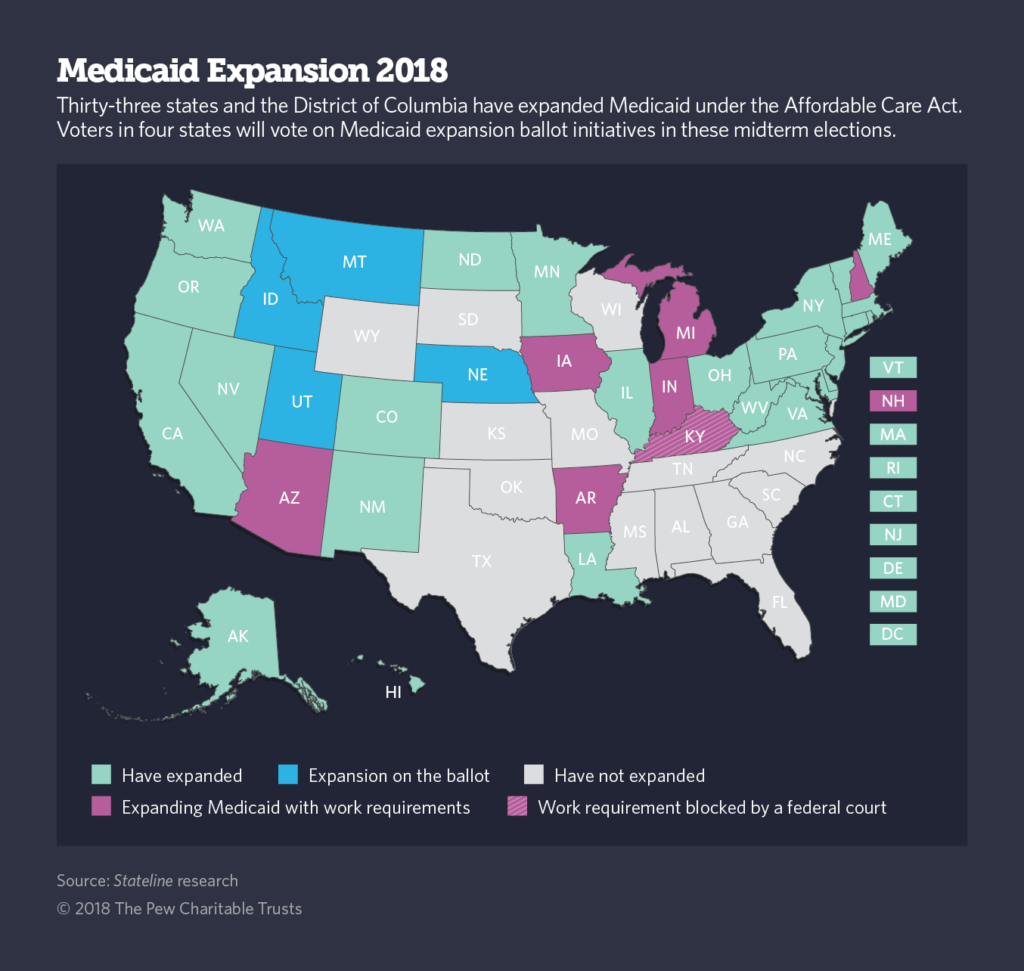

Nebraska isn’t the only red state where residents have forced expansion onto Tuesday’s ballot. Idaho and Utah voters also will vote on citizen-initiated measures on Medicaid expansion. Montana, meanwhile, will decide whether to make its expansion permanent. The majority-Republican legislature expanded Medicaid in 2015, but only for a four-year period that ends next July.

Polling in those three states indicate a majority supports expanding Medicaid. Like Nebraska, all are heavily Republican states easily captured by Trump in 2016.

Last year’s failed attempt by Trump and congressional Republicans to unravel Obamacare revealed the popularity of the ACA with voters. Health policy experts said it also helped educate the public about the benefits of Medicaid, prompting activists in the four states to circumvent their Republican-led legislatures and take the matter directly to the voters.

Activists also were encouraged by the example of Maine, where nearly 60 percent of voters last year approved Medicaid expansion after the state’s Republican governor vetoed expansion bills five times.

“Medicaid has always polled well,” said Joan Alker, executive director of the Center for Children and Families at Georgetown. “When you explain what it does, they think it’s a good idea. What has changed is the intensity and growing recognition that states without expansion are falling further behind, especially in rural areas where hospitals are closing at an alarming rate.

“And all of the states with these ballot initiatives this year have significant rural populations.”

For many in Nebraska, the argument — advanced in one anti-427 television ad — that Medicaid is a government handout to lazy, poor people simply doesn’t square with what they know.

“These aren’t lazy, no-good people who refuse to work,” said Block, a middle school teacher, in an exasperating tone you can imagine her using in an unruly classroom. “They’re grocery store baggers, home health workers, hairdressers. They are the hardest workers in the world, who shouldn’t have to choose between paying for rent or food and paying for medicine or to see a doctor.”

Extending Benefits to Childless Adults

The initiative campaign began after the Nebraska legislature refused to take up expansion again last year. Its early organizers were, among others, a couple of Democratic senators and a nonprofit called Nebraska Appleseed.

Calling itself “Insure the Good Life,” an expansion of the state slogan, the campaign needed nearly 85,000 signatures to get onto the ballot. In July, the group submitted 136,000 signatures gathered from all 93 Nebraska counties.

The initiative would expand Medicaid to childless adults whose income is 138 percent of the federal poverty line or less. For an individual in Nebraska, that would translate to an income of $16,753 or less. Right now, Nebraska is one of 17 states that don’t extend Medicaid benefits to childless adults, no matter how low their income.

Under Medicaid expansion, the federal government would pay 90 percent of the health care costs of newly eligible enrollees, and the state would be responsible for the rest. The federal match for those currently covered by Medicaid is just above 52 percent.

The Nebraska Legislative Fiscal Office, a nonprofit branch of the legislature, found in an analysis that expansion would bring an additional 87,000 Nebraskans into Medicaid at an added cost to the state of close to $40 million a year. The current Medicaid population in Nebraska is about 245,000.

The federal government would send an additional $570 million a year to cover the new enrollees. An analysis from University of Nebraska commissioned by the Nebraska Hospital Association, a backer of the initiative, found the new monies also would produce 10,800 new jobs and help bolster the precarious financial situation of the state’s rural hospitals.

For economic reasons alone, not expanding makes little sense, said state Sen. John McCollister, one of two Republican senators openly supporting expansion and a sponsor of expansion bills in the legislature, over coffee in an Omaha cafe one day recently.

“Nebraska is sending money to Washington, and that money is being sent back to 33 other states and not to Nebraska,” he said. “It’s obviously good for 90,000 Nebraskans by giving them longevity and a higher quality of life, but it also leads to a better workforce and benefits rural hospitals that won’t have to spend so much on uncompensated care.”

He said the state could easily raise the necessary money by increasing taxes on medical providers, cigarettes and internet sales. If 427 passes, those will be decisions for the next legislature.

Among the measure’s opponents is Americans for Prosperity, a libertarian advocacy group funded by David and Charles Koch that has been running radio ads against the initiative. Jessica Shelburn, the group’s state director in Nebraska, said her primary concern is that expansion would divert precious state resources and prompt cutbacks in the current optional services Medicaid provides.

“While proponents have their hearts in the right place,” Shelburn said, “we could end up hurting the people Medicaid is intended to help.”

Georgetown’s Alker, however, said that no expansion state has curtailed Medicaid services.

When the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010, it mandated that all states expand Medicaid, but a 2012 U.S. Supreme Court ruling made expansion optional for the states. As of now, 33 states and Washington, D.C., have expanded, including states that tend to vote Republican, such as Alaska, Arkansas and Indiana.

Expansion is not an election issue only in the states with ballot initiatives this year. Democratic gubernatorial candidates are making expansion a major part of their campaigns in Florida and Georgia.

Ashley Anderson, a 25-year-old from Omaha with epilepsy, is one of those anxiously hoping for passage in Nebraska. A rosy-faced woman, she wears a red polo shirt from OfficeMax, where she works part-time for $9.50 an hour in the print center. She aged out of Medicaid at 19, and her single mother can’t afford a family health plan through her employer.

Since then, because of Anderson’s semi-regular seizures, she says she can’t take a full-time job that provides health benefits, and private insurance is beyond her means.

Because Anderson also can’t afford to see a neurologist, she is still taking the medication she was prescribed as a child, even though it causes severe side effects.

Not long ago, Anderson had a grand mal seizure, which entailed convulsions and violent vomiting, and was taken by ambulance to the emergency room. That trip left her $2,000 in debt. For that reason, she said, “At this point, I won’t even call 911.”

Anderson might well qualify for Social Security disability benefits, which would entitle her to Medicaid, but she said the application process is laborious and requires documentation she does not have. As far as she is concerned, the initiative is her only hope for a change.

“You know what, I even miss having an MRI,” she said. “I’m supposed to have one every year.” She can’t remember the last time she had one.

For the uninsured, the alternatives are emergency rooms or federally qualified health centers, which do not turn away anyone because of poverty.

While the clinics provide primary care, dental care and mental health treatment, they cannot provide specialty care or perform diagnostic tests such as MRIs or CAT scans, said Ken McMorris, CEO of Charles Drew Health Center, the oldest community health center in Nebraska, which served just under 12,000 patients last year.

Almost all its patients have incomes below 200 percent of poverty, McMorris said. Many have little access to healthy foods and little opportunity for exercise.

William Ostdiek, the clinic’s chief medical officer, said he constantly sees patients with chronic conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease whose symptoms are getting worse because they cannot afford to see specialists.

“It’s becomes a vicious cycle,” he said. “They face financial barriers to the treatments they need, which would enable them to have full, productive lives. Instead, they just get sicker and sicker.”

Expansion, McMorris said, would make all the difference for many of those patients.

Some county officials also hope for passage. Mary Ann Borgeson, a Republican county commissioner in Douglas County, which includes Omaha, said her board has always urged the legislature to pass expansion. “Most people don’t understand — for counties the Medicaid is a lifeline for many people who otherwise lack health care.”

Consequently, she said, the county pays about $2 million a year to reimburse providers for giving care to people who don’t qualify for Medicaid and can’t afford treatment, money that would otherwise be in the pockets of county residents.

‘That Is Socialism’

Insure the Good Life has raised $2.2 million in support of 427, according to campaign finance reports and Meg Mandy, who directs the campaign. Significant contributions have come from outside the state, particularly from Families USA, a Washington-based advocacy organization promoting health care for all, and the Fairness Project, a California organization that supports economic justice.

Both groups are active in the other states with expansion on the ballot. Well-financed, the proponents have a visible ground game and a robust television campaign.

The opposition, much less evident, is led by an anti-tax Nebraska organization called the Alliance for Taxpayers, which has filed no campaign finance documents with the state.

Marc Kaschke, former mayor of North Platte, said he is the organization’s president, but referred all questions about finances to an attorney, Gail Gitcho, who did not respond to messages left at her office.

Gitcho had previously told the Omaha World-Herald that the group hadn’t been required to file finance reports because its ads only provided information about 427; it doesn’t directly ask voters to cast ballots against the initiative.

Last week, the Alliance for Taxpayers began airing its first campaign ads. One of them complains that the expansion would give “free health care” to able-bodied adults. It features a young, healthy looking, bearded man, slouched on a couch and eating potato chips, with crumbs spilled over his chest.

In a phone interview, Kaschke made familiar arguments against expansion. He said the state can’t afford the expansion, that it would drain money from other priorities, such as schools and roads. He said he fears the federal government would one day stop paying its share, leaving the states to pay for the whole program.

He also said, repeating Shelburn’s claim, that with limited funds, the state would be forced to cut back services to the existing population.

“We feel the states would be in a better position to solve this problem of health care,” Kaschke said. He didn’t offer suggestions on how.

Outside influence ruffles many Nebraska voters. Duane Lienemann, a retired public school agricultural teacher from Webster County near the Kansas line, said he resents outside groups coming to the state telling Nebraskans how to vote.

And he resents “liberals” from Omaha trying to shove their beliefs down the throats of those living in rural areas.

Their beliefs about expansion don’t fly with him.

“I think history will tell you when you take money away from taxpayers and give it to people as an entitlement, it is not sustainable,” Lienemann said. “You cannot grow an economy through transferring money by the government. That is socialism.”

It’s a view shared by Nebraska’s Republican governor, Pete Ricketts. He is on record opposing the expansion, repeating claims that it would force cutbacks in other government services and disputing claims, documented in expansion states, that expansion leads to job growth. But Ricketts has not made opposition to expansion a central part of his campaign.

Whether he would follow in the path of Maine’s Republican governor, Paul LePage, and seek to block implementation of the expansion if the initiative passed, is not clear. Ricketts’ office declined an interview request and did not clarify his position on blocking implementation.

For his part, Scheer, the speaker of the legislature, said he would have no part of that. “We’re elected to fulfill the wishes of the people,” he said. “If it passes, the people spoke.”