By Julie Appleby, Kaiser Health News

(Courtesy of Lauren Cutshall)

Caitlin and Corey Gaffer know they made a mistake.

Anyone could have done the same thing, the Minneapolis couple says. Still, they can’t believe it cost them their health insurance coverage just as Caitlin was in the middle of pregnancy with their first child.

“I was like ‘What?’ There’s no way that’s possible,” said Caitlin, 31, of her reaction to the letter she opened in early October telling them the coverage they had for nearly two years had been canceled. It cited nonpayment of their premium as the reason.

Except they had paid the bill, they thought.

The Gaffers’ snafu — and their marathon battle to correct the error with insurer HealthPartners — is featured in the podcast “An Arm and a Leg,” which launches its second season this week and is co-produced by Kaiser Health News.

Like the Gaffers, tens of thousands of Americans each year — exact counts aren’t available — are dropped by their insurers over payment issues, sometimes with little or no prior warning from their insurers.

The question is: Can insurers cancel people with little or no notice? The answer is yes … and no. Like so many issues in American health care, it is surprisingly complicated.

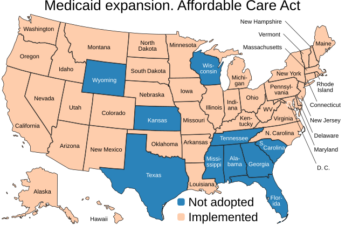

This is one problem the Affordable Care Act was designed to fix. Certainly, safeguards were put in place. Insurers can’t cancel people when they fall ill, for example. But the protections for being dropped for a missed payment are uneven. Consumers who get an ACA subsidy have more protection than those who don’t.

The Gaffers didn’t qualify for a subsidy. So they were subject to state law. Minnesota’s law requires insurers to provide at least 30 days’ notice before canceling, said Scott Smith, spokesman for the state Department of Health, which regulates HMOs. However, an administrative rule seems to undercut that requirement.

The Gaffers didn’t get a notice, they say. Their efforts to correct their error were stymied until Dan Weissmann, creator and host of “An Arm and A Leg,” started making inquiries about their case.

Misfired payments

The problem for the Gaffers started in early September. They changed checking accounts and had to set up all new online payments. When they made their monthly $730 health insurance premium payment, they mistakenly sent it to a hospital owned by HealthPartners rather than the health plan itself.

The hospital didn’t let the health plan know it had a payment from the Gaffers. Compounding the problem, the couple sent their October payment a couple of weeks later to the correct place but had insufficient funds to cover the amount.

The Gaffers got a letter from HealthPartners dated Oct. 8 canceling coverage back to mid-September. Caitlin was six months pregnant.

“It was a busy time in our life,” said Corey, 32, who runs an architectural photography studio. “We made these two little mistakes, but were never given any notice that we were making mistakes until after the fact.”

Why didn’t the hospital and health plan communicate about the misdirected payment? After all, they are part of the same system and that could have avoided the problem altogether.

HealthPartners spokeswoman Rebecca Johnson said its hospitals are supposed to notify the health plan if they receive premium payments in error, but said that “even though we have this process, we are not always notified of this or not notified in a timely fashion.”

As far as a past-due notice to the Gaffers, Johnson said HealthPartners’ policy at the time was to include information on monthly statements about outstanding balances.

That, however, is different from getting a warning that “you will be canceled as of this date,” said JoAnn Volk, a research professor at the Georgetown University Center on Health Insurance Reforms.

Still, the Gaffers’ story does have a happy ending — including an apology and some new notification practices by HealthPartners — but not before they racked up lots of stress and nearly $30,000 in medical bills incurred while Caitlin was uninsured briefly during her complicated pregnancy.

Same Insurance, Different Rules

The ACA bars insurers from retroactively canceling policies if consumers fall ill or discover they are pregnant —things that could have occurred in most states before the federal law passed.

But it does allow allows cancellations for two reasons: false information on an application or failure to pay premiums.

Those who qualify for a tax credit — because they earn less than 400% of the federal poverty level, or roughly $50,000 for an individual — get a 90-day grace period after missing a payment. Also, the law requires insurers to notify those policyholders that they have fallen behind and face cancellation. If payment is made in full before the end of the 90-day grace period, they are reinstated. If not, they’re canceled and medical costs incurred in the second and third months of the grace period fall on the consumer.

This policy keeps federal subsidy dollars flowing to insurers during the grace period, even if a consumer has a financial wobble.

It’s different for people like the Gaffers, however, who make too much for a subsidy. They are subject to state laws and can be dropped much more abruptly.

Most states have a 30-day grace period to make a payment after the premium is due, said Tara Straw, a senior policy analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. But how much prior notice insurers must give before canceling — if any — varies by state.

“In most states, plans would balk at also having to send a notice of delinquent premium,” said Straw. “But notice is important for consumers so they can correct the situation and make the payment, especially in a case like this where they made an honest mistake.”

It’s a policy that harks back to a time before the ACA when individual consumers could be dropped for almost any reason. It isn’t clear why the Gaffers received no notice.

Spokeswoman Johnson, when asked about the state requirement, wrote: “Members are notified of any outstanding balance on their monthly premium statements. They have a 30-day grace period.”

HealthPartners told the state’s insurance exchange as part of an inquiry into the Gaffer’s case, that “as far as past-due notices go, we do not send letters for members that do not have [a subsidy],” an appeals document shows.

Following the attention on the Gaffer’s plight, HealthPartners has a new policy, rolled out in March and April for customers who don’t get subsidies: Those who fall behind will get a late notice around the 15th of the month, said spokeswoman Johnson.

That might have helped the Gaffers, but it is still far less time than the 90-day window the insurer must give by law to anyone who bought the same insurance plan but got a subsidy.

An Apology

As for the Gaffers, who scrambled for months trying to get coverage and went uninsured for a while, there’s good news.

First, they got new coverage from a different insurer before they welcomed baby Maggie, born without a hitch and healthy in late January.

Months later, after fielding questions from “An Arm and a Leg,” HealthPartners called the Gaffers: It wanted to reinstate them — and cover the outstanding medical bills racked up during their time uninsured.

“We’ve apologized to the family, reinstated their coverage and view this situation as an opportunity where we can do better,” spokeswoman Johnson said in an email.

The Gaffers have learned a lot in the process.

“Being an advocate for yourself is such a huge thing,” said Corey.

He’s glad HealthPartners has now said it will send warnings to consumers who fall behind on payments.

Oh, and just to be sure, the couple’s premiums are now on “auto pay” and “we have like eight calendar reminders set up,” Caitlin said. “Today it popped up three times: ‘Make sure insurance is paid.’”

Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit health newsroom whose stories appear in news outlets nationwide, is an editorially independent part of the Kaiser Family Foundation.