By Marshall Allen, ProPublica

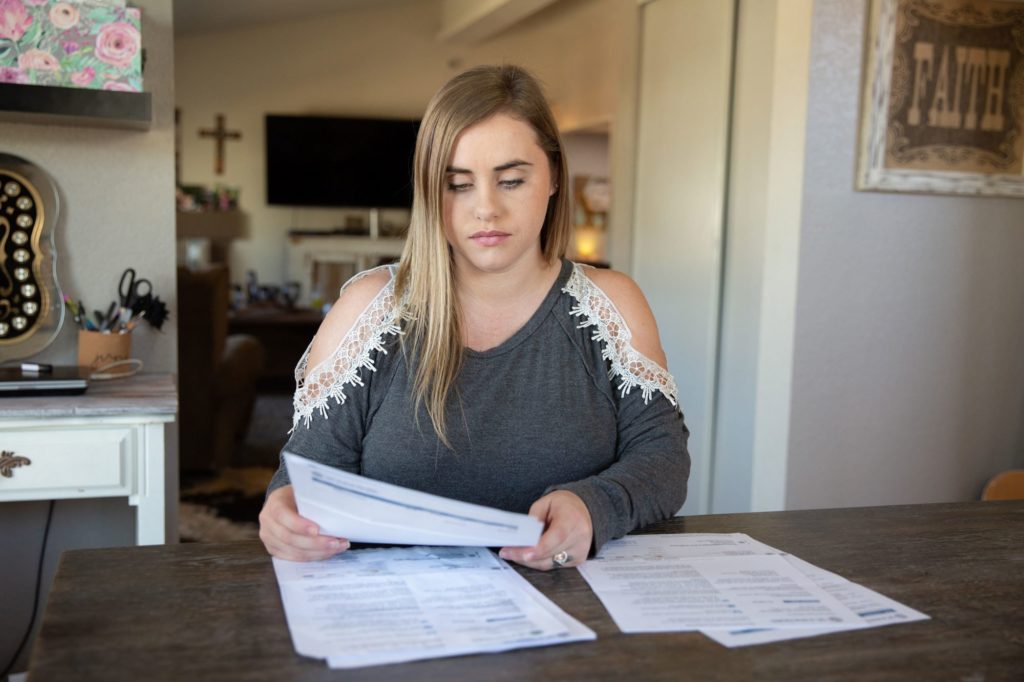

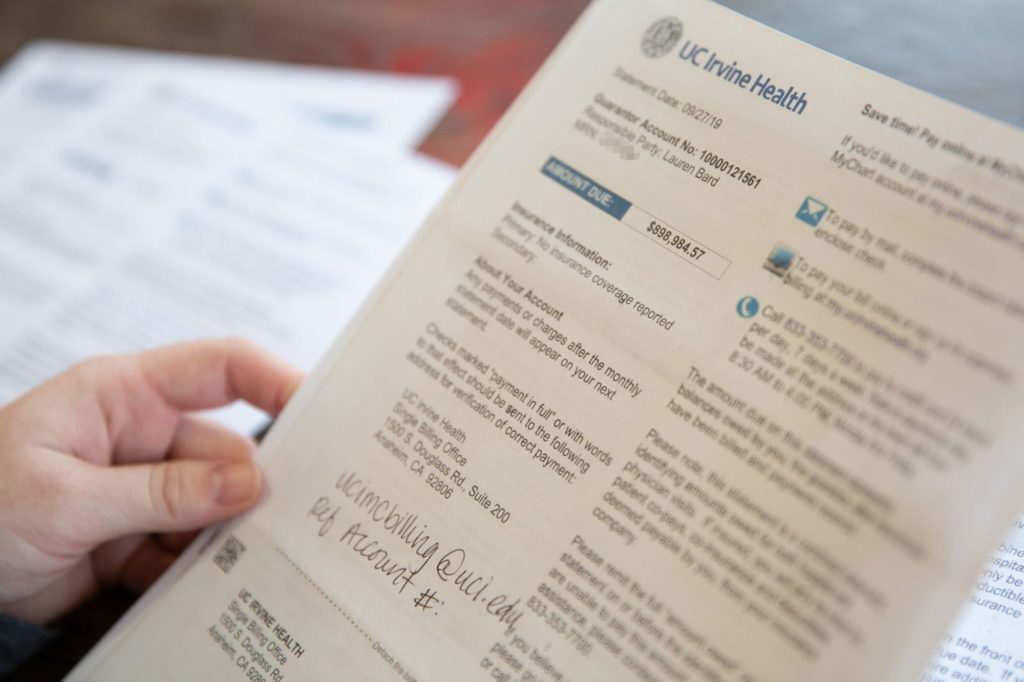

Lauren Bard opened the hospital bill this month and her body went numb. In bold block letters it said, “AMOUNT DUE: $898,984.57.”

Last fall, Bard’s daughter, Sadie, had arrived about three months prematurely; and as a nurse herself, Bard knew the costs for Sadie’s care would be high.

But she’d assumed the bulk would be covered by the organization that owned the hospital where she worked: Dignity Health, whose marketing motto is “Hello humankindness.”

She would be wrong.

Bard, 30, had been caught up in an unforgiving trend. As health care costs continue to rise, employers are shifting the expense to their workers — cutting back on what they’ll cover or pumping up premiums and out-of-pocket costs.

But a premature baby, delivered with gaspingly high medical claims, creates a sort of benefits bomb, the kind an employer — especially one funding its own benefits — might look for a way to dodge altogether.

Bard, distracted by her daughter’s precarious health and her own hospitalization for serious pregnancy-related conditions, found this out the hard way. Her battle against her own employer is a cautionary tale for every expectant parent.

Bard’s saga began, traumatically, when she gave birth to Sadie at just 26 weeks on Sept. 21, 2018, at the University of California, Irvine Medical Center in Southern California.

Weighing less than a pound and a half, tiny enough to fit into Bard’s cupped hands, Sadie was rushed to the neonatal intensive care unit.

Three days after her birth, Bard called Anthem Blue Cross, which administers her health plan, to start coverage. Anthem and UC Irvine’s billing department assured her that Sadie was covered, Bard said.

But Dignity’s plan, like many, requires employees to enroll newborns within 31 days through its website, or they won’t be covered — something Bard said she didn’t know at the time.

Meanwhile, believing that everything with her health benefits was on track, Bard spent nine of those first 31 days recovering in her own hospital bed and then had to return to the emergency room because of a subsequent infection.

She spent as much time as she could in the neonatal intensive care unit, where Sadie, in an incubator, attached to tubes and wires, battled a host of critical ailments related to extremely premature birth. At times, doctors gave her a 50-50 chance of survival.

“Right from birth she was a fighter,” Bard said.

Then, eight days past the 31-day deadline, UC Irvine’s billing department alerted Bard to a problem with Sadie’s coverage. Anthem was saying it could not process the claims for the baby, who was still in the NICU.

Bard, an emergency room nurse at St. Bernardine Medical Center in San Bernardino, called Dignity’s benefits department and made a sickening discovery. Sadie wasn’t enrolled in its health plan. It was too late, she was told, she could no longer add her baby.

Dignity bills itself as the fifth-largest health system in the country, with services in 21 states. The massive nonprofit self-funds its benefits, meaning it bears the cost of bills like Sadie’s. And it doesn’t appear to be short on cash.

In 2018, the organization reported $6.6 billion in net assets and paid its CEO $11.9 million in reportable compensation, according to tax filings. That same year, more than two dozen Dignity executives earned more than $1 million in compensation, records show.

Dignity is also a religious organization that says its mission is to further “the healing ministry of Jesus.” Surely, Bard remembering thinking, they would show her compassion.

With the specter of the bills hanging over her, Bard said she literally begged Dignity to change its mind in multiple phone calls, working her way up to supervisors. She thought she’d enrolled Sadie by calling Anthem she told them. It was an innocent mistake.

The benefits representatives told her information about the 31-day rule was in the documents she received when she was hired. It didn’t matter that it was six years earlier, long before she dreamed of having Sadie, she said. The representative also told her it wasn’t just Dignity’s decision, the Internal Revenue Service wouldn’t allow them to add the baby to the plan.

Under Dignity’s plan, Bard could have two written appeals. She got nowhere with either of them. “IRS regulations and plan provisions preclude us from making an enrollment exception,” Dignity wrote in its Nov. 30, 2018, response to her first appeal.

IRS officials said they can’t talk about specific cases because of privacy issues and could not comment in general in time to meet ProPublica’s deadline.

Dignity rejected Bard’s second written appeal in a July 8 letter, saying the deadline was included in a packet sent nine days before Sadie’s birth. But at that time, Bard had already been admitted to the hospital because of complications. Dignity’s letter said it “cannot make an exception to plan provisions.”

But the federal regulator of Dignity’s plan said such plans can, in fact, make exceptions. An official with the federal Labor Department, which regulates self-funded health benefits, told ProPublica that plans can make concessions as long as they apply them equally to participants. Plus, federal law allows plans to treat people with “adverse health factors” more favorably, the official said.

Bard scrambled, futilely, to see if any publicly funded insurance plan would be able to cover the costs. Meanwhile, the bills began arriving: $206 in November, $1,033 in January, $523 in February and $69,362 in April, with the biggest yet to come. Sadie had spent 105 days in the hospital and had several surgeries — and the bills would be Bard’s alone.

Sadie’s total hospital tab was nearing $1 million and climbing when ProPublica first spoke to Bard. “I’ll either work the rest of my life or file for bankruptcy,” she said.

Bard said she and her fiancé — Sadie’s father, Nathan Benton — considered delaying their wedding so he wouldn’t be legally saddled with the bills as well.

The looming debt, and her employer’s rejection, sent Bard reeling when she was already suffering from postpartum depression. She went back to her job while worrying that she might lose her home in Norco. She wept and beat herself up again and again about missing the deadline: How could she not think of something like that? She should’ve known. She should’ve been on top of it more.

Anthem declined to comment for this story. UC Irvine, where Bard said the care was excellent, said that cases like Bard’s are unusual but may happen in 1% to 2% of births. The hospital tries to work with patients when they get stuck with the bills, a UC Irvine spokesman said.

With the appeals exhausted, the $898,000 bill landed. Bard could see right away that handling it the typical way, with a payment plan, was not going to work. If she chipped away at it at $100 a month, settling the obligation would take more than 748 years. “It would take so long I’d be dead,” Bard said.

Bard could see no way out. On Oct. 7, she posted a photograph of the $898,000 bill on Facebook. “When Dignity Health (the company I work for) screws you out of your daughter’s insurance…” she wrote.

A week later, ProPublica, which had been flagged to Bard’s case while reporting about health insurance excesses, contacted a Dignity media representative.

The next day, Bard got a call from the senior vice president of operations for Dignity Southern California, who apologized and said she’d heard about the situation from the organization’s media team and would help. Two days later, Dignity added Sadie to the plan, retroactive to her birth date. It would cover the bills.

Dignity officials told ProPublica that they’d learned about Bard through her Facebook post. Bard said she doubts Dignity would have reversed course without the questions from ProPublica.

Dignity said in a statement that it would review how it could better educate new parents about the enrollment requirement. But Bard still wants to know why her employer would make her suffer through such an ordeal. In a letter Bard received last week, the Dignity benefits department said it had received additional information that caused it to reverse course, but it appears to be the same information that Bard had been telling it all along.

“We based this new decision on certain extenuating and compelling circumstances, which, in all likelihood prohibited you from enrolling your newborn daughter within the Plan’s required 31-day enrollment period,” the letter said.

Bard recognizes a dark irony in her Christian employer’s behavior, and it’s made her skeptical. She urged the benefits department to change its process so other employees don’t also have their benefits denied. Dignity needs to put its own ideals into practice, she told ProPublica. “You can’t put on this facade,” Bard said. “You have to live it. You have to walk the walk.”

Bard said she and Benton still don’t know the final total for Sadie’s care. But they sometimes call the sassy and dimpled 1-year-old, who is healthy and reaching developmental milestones, their “million-dollar baby.”

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.