By Christine Vestal, Stateline

PHILADELPHIA — In a massive, soot-stained 19th century former Methodist church that fills an entire block here, dozens of addiction counselors and peer support specialists work to help injection drug users stay as healthy as possible until they decide they’re ready for treatment. And then they help them find it.

Called Prevention Point Philadelphia, the 28-year-old syringe exchange center also provides packages of the opioid overdose antidote naloxone to anyone who wants it, to rescue fellow drug users who overdose.

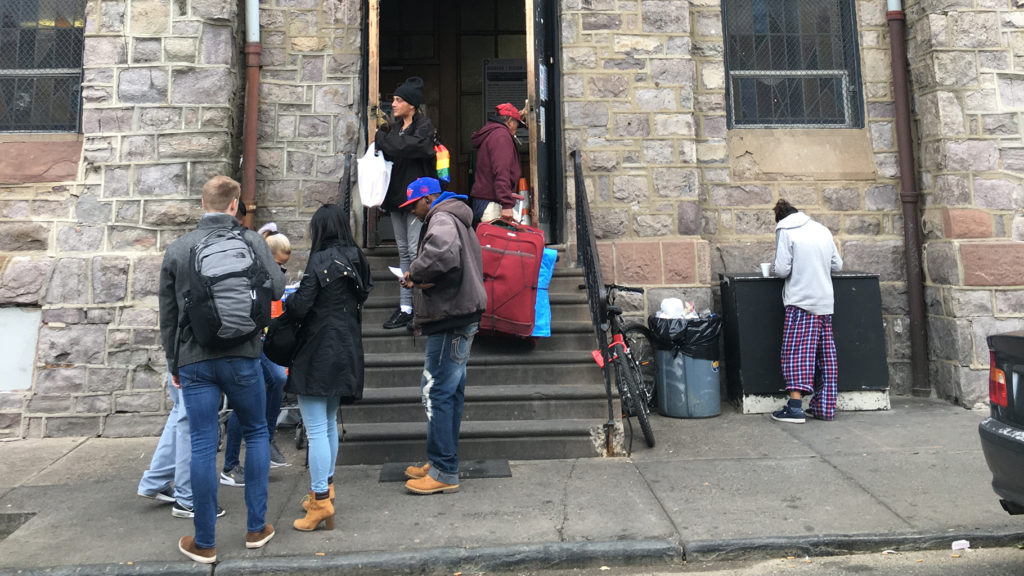

On a chilly afternoon this month, a crowd of regulars at the storied center in east Philadelphia’s drug-blighted Kensington neighborhood were signing up to receive a fresh supply of the life-saving drug at a card table outside. Visitors hugged staffers and one another before departing what most in this once-thriving industrial section of the city call a valuable community resource.

Without Prevention Point and naloxone, Philadelphia health commissioner Thomas Farley estimates, the city’s already staggering overdose death toll — more than 1,100 last year in a city of 1.6 million — would be much higher.

But he and others here say much more needs to be done. Even if it means charting new territory.

A preliminary decision by a federal judge last month could put Philadelphia on a path to becoming the first U.S. city to host a so-called safe injection facility, where users can come in off the street and consume their illicit drugs under the watchful eyes of medical professionals who will rescue them if they overdose.

Politicians and harm-reduction advocates in Boston, Denver, New York, San Francisco and Seattle have tried to open similar facilities but have been stalled by red tape and state and local opposition, as well as federal lawsuit threats.

And lawmakers in Maryland, California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, New York and Vermont, who have proposed bills that would authorize and fund supervised injection sites, have met similar opposition.

“People come running in screaming, ‘We have an overdose on the corner.’”

Jose Benitez, president Safehouse

A 2018 report by Vermont Republican Gov. Phil Scott’s opioid commission found that safe injection sites were not a viable option because they were illegal under federal law and “highly controversial.” And then-California Gov. Jerry Brown, a Democrat, vetoed a safe injection site bill in 2018 for similar reasons.

When Prevention Point opened its doors in 1991, possession of a syringe was a state crime. Then-Mayor Ed Rendell, a Democrat who later served as governor, supported the program anyway and issued an executive order allowing syringe exchanges in the city, because he said too many Philadelphians were dying of HIV/AIDS, which was spreading through injection drug use.

Shortly after it opened, the state police threatened to arrest Prevention Point’s operators and participants, but Rendell said he told them to come to his office and arrest him instead. That didn’t happen.

Today, the center serves 15,000 people each year and is one of the largest in the United States.

As the opioid overdose death toll shifts from rural America to major urban centers, Philadelphia has become the epicenter.

The rate of overdose deaths here — 65 per 100,000 residents — was the highest of any major city in the nation and over three times the national average in 2017, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

And its heroin and illicit fentanyl supply is the cheapest, most plentiful and deadliest in the United States, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

‘Far From Over’

In October, U.S. District Judge Gerald McHugh denied a petition, filed by the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, arguing that safe injection or overdose prevention sites violate a 2003 provision in the federal Controlled Substances Act known as the “crack house” statute, which bans the operation of a facility for the purpose of using illegal drugs.

In his first-in-the-nation ruling, McHugh found that Safehouse, a Philadelphia-based nonprofit, would not violate federal law by opening a supervised injection site in the city. He found that the purpose of the proposed site was not to facilitate drug use, but to save lives and reduce drug consumption by helping more people get into treatment.

U.S. Attorney William McSwain, who filed the lawsuit against Safehouse in February, swiftly vowed to appeal the final decision and use all available enforcement measures — including asset seizures and prison sentences of up to 25 years — to stop the facility from opening.

Read more Stateline coverage of the opioid epidemic.

“The Department of Justice remains committed to preventing illegal drug injection sites from opening,” McSwain said in a statement. “Today’s opinion is merely the first step in a much longer legal process that will play out. This case is obviously far from over.”

Rendell — the former Philadelphia mayor and Pennsylvania governor who is on the board of Safehouse — has repeatedly said he’s willing to be arrested for opening the country’s first safe injection site. “They can come and arrest me first,” he said last year in an NPR interview.

Moving Forward

For now, Safehouse has permission to pursue the project.

“Advocates across the country are watching Philadelphia,” said Daniel Raymond, policy director for the New York-based Harm Reduction Coalition. “Somebody had to go first.

“The federal court ruling isn’t final, and it isn’t binding in other states, but it gives encouragement to cities and health departments to say, ‘You know what? This isn’t so crazy after all,’” Raymond said. “Now it’s a question of when, not whether.”

By the end of the year, McHugh is expected to issue a final order in the case.

“We feel confident we’ll get a final decision in our favor, given that the judge’s opinion was based on the idea that our purpose was to provide medical care and actually to discourage drug use, not to facilitate it,” said Ilana Eisenstein, an attorney with Philadelphia-based international business law firm DLA Piper who is arguing the case for Safehouse.

Until then, city officials, including Democratic Mayor Jim Kenney and District Attorney Larry Krasner, are working with Safehouse President Jose Benitez and the city’s police department on a plan for keeping the peace, discouraging drug dealing and ensuring users won’t be arrested for consuming illicit drugs around the proposed facility.

According to Benitez, the group plans to open several brick-and-mortar sites in the city, as well as deploy mobile units to extend their reach.

“This is a citywide problem,” he said. “We need more than one of these and we need them in different parts of the city.

“We’re hoping to have multiple sites opening up in ZIP codes with the most overdose deaths and to have mobile units move around the city to normalize this a little bit.”

Even one facility, if opened in Kensington, could save 50 lives every year based on the number of overdose deaths already occurring in that area, said Farley, the city’s health commissioner. “It would be a valuable adjunct to the other things we’re doing to prevent overdoses in the city.”

Fentanyl Has Changed Everything

For more than three decades, staff at safe injection sites in Australia, Canada and Europe have invited tens of thousands of illicit drug users to consume heroin and other drugs in supervised facilities instead of in back alleys and parks.

Research indicates the facilities have reduced overdose deaths and lowered overall drug consumption in their surrounding neighborhoods.

In Vancouver, Canada, for example, where the safe injection center Insite has operated since 2001, drug overdose deaths declined 35% in the neighborhood and 9% in the rest of the city between 2001 and 2005. And 30% more drug users got into treatment, according to surveys conducted at the University of British Columbia.

Safehouse plans to open its first supervised injection facility in Kensington, where, on a recent day, people could be seen shooting heroin on nearly every block as police and emergency medical teams stood by.

Drug use has been a part of daily life for many Kensington residents for decades, but the death toll has never been as high as in the past five years.

According to Benitez, who runs Prevention Point, “Fentanyl has changed everything. Instead of using four times a day, people are shooting up eight to 12 times a day. And when they overdose, we have much less time to rescue them.

“We’re now experiencing two to three overdoses on most days. People are using outside of the [Prevention Point] building and then walking in and overdosing. Or they use in our bathrooms and overdose. Or people come running in screaming, ‘We have an overdose on the corner.’

“That’s what we’re up against.”

At the more than 300 syringe exchanges around the country, drug users can get clean needles and syringes, testing for hepatitis C and HIV/AIDS and wound care and other medical services. They also can get help finding addiction treatment.

“But then we tell them to go outside and use their drugs between parked cars or under stoops using puddle water,” Benitez said. “Why not provide a clean, well-lighted place for them to consume drugs so we know where they are and can rescue them if they overdose?”

Nationwide, many drug users are aware that syringe exchange centers have naloxone on hand. If they’re concerned about whether their stash might have fentanyl in it, they drop in and use their drugs in the bathroom so someone will rescue them if they overdose. Most syringe exchanges also offer test strips to detect fentanyl.

In New York’s Washington Heights neighborhood in the northern tip of Manhattan, for example, it’s an open secret that the syringe exchange center Corner Project keeps track of how long people have been in the bathroom, so they can open the door and rescue them with naloxone if they’ve overdosed.

Softening Opposition

In other cities and states, proponents of safe injection sites sought financial support from their legislatures and the backing of public health and law enforcement officials, local politicians and residents, and businesses before launching a facility. But those broad-based initiatives so far have not worked.

Safehouse, a privately funded nonprofit, decided to take a different route.

“We decided, ‘Nah, it’s not going to work that way in Philadelphia,’” said Ronda Goldfein, executive director of the AIDS Law Project of Pennsylvania, which is a partner in the project. “Instead, we decided to work with private funders and not get bogged down with all the politics.”

Immediately following McHugh’s ruling in favor of Safehouse, two Democratic state senators who represent Philadelphia, Anthony Williams and Christine Tartaglione, announced plans to introduce a bill that would ban supervised injection sites from operating anywhere in the state, arguing they violated federal law and could attract drug users.

But later in the month, the two lawmakers revised their proposal, allowing municipalities the option of authorizing supervised injection sites as long as they held public hearings, had a medical professional on site and included a policing plan. The bill was filed in late October. It has six new sponsors, including five Republicans.

On Nov. 7, Williams announced plans to repeal the statewide ban on syringe possession by amending the state’s controlled substances statute. “As Pennsylvanians continue to deal with the impact of the opioid crisis,” he said, “syringe exchange programs should be allowed to operate freely across the commonwealth.”

Average Americans, including many Philadelphians, consider safe injection sites a bridge too far.

A national survey published by Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health last year found only 29% of respondents supported legalizing safe injection sites in their communities. Support for syringe services was 39%.

But a poll of Philadelphians — funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts, which also supports Stateline — found residents roughly split in their approval of the proposed safe injection site.

Public opinion toward syringe exchanges is softening, said Raymond with the Harm Reduction Coalition. Republicans are starting to favor them because they ultimately save the government tons of money, he said.

But hurdles to opening a safe injection site remain steep in most places. In Philadelphia, even drug users who stand to benefit from the centers have said they’re concerned about getting arrested, said Farley, the health commissioner.

And beleaguered Kensington residents who regularly encounter people overdosing on the sidewalks have reportedly said in local council meetings that they worry that a safe injection site would attract drug users and that drug dealers would follow them.

But a study by the Rand Corporation found that hasn’t happened in countries where safe injection sites have operated for decades.

Stateline is an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy. Since its founding in 1998, Stateline has maintained a commitment to the highest standards of non-partisanship, objectivity, and integrity. Its team of veteran journalists combines original reporting with a roundup of the latest news from sources around the country. Stateline focuses on four topics that are key to state policy: fiscal and economic issues, health care, demographics, and the business of government.