By Michael Ollove, Stateline

All states but one — Idaho — that operate their own Obamacare health insurance exchanges have opened or extended enrollment periods so people previously without insurance can sign up now. Nearly all have cut red tape and suspended in-person meetings.

At least five states — Arizona, Florida, Idaho, Indiana and Montana — have gotten rid of either Medicaid or CHIP premiums and copayments. Many states are relaxing enrollment red tape in Medicaid and its sister program, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, known as CHIP, and allowing people to sign up and submit documentation later.

Kentucky has gone further. It has opened Medicaid to any Kentuckians without health insurance, regardless of their income, until June 30.

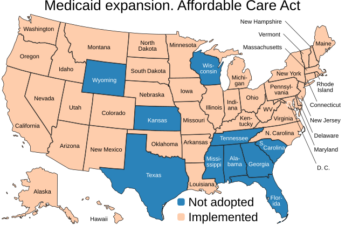

Two roadblocks — the lack of Medicaid expansion in some states and the refusal of the federal government to open Obamacare exchanges in others — remain for many Americans, however.

Fourteen states, mostly in the South, have not yet expanded Medicaid eligibility, which even before the COVID-19 pandemic left 4.4 million non-elderly adultswithout a health insurance option, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Medicaid and CHIP are for lower-income Americans. The Obamacare health insurance marketplaces are where others, not covered by employer-sponsored health plans, can buy health insurance plans, often with the help of federal tax credits.

Employer Insurance

As was true before the COVID-19 outbreak, those who lose their jobs and, as a result, their employer-sponsored health insurance, can enroll in Obamacare health plans regardless of where they live. They also could continue their employer health insurance under the federal law known as COBRA, though premiums can be costly.

Those who were already without health insurance, however, have that option only if they live in one of 11 states plus Washington, D.C., that operate their own health insurance exchanges and are allowing previously uninsured people to enroll.

Colorado, one of the states that operates its own exchange, opened up a special enrollment period because of the COVID-19 crisis. Shawna Royer-Gravlin, who lives in Longmont, was one of the Coloradans who took advantage of the opportunity. Royer-Gravlin, who has arthritis and nerve damage, had lost her Medicaid coverage in November because her income was too high, and it was too late then to sign up during the normal open enrollment period in Colorado. But about two weeks ago, she and her husband Bruce Gravlin received a text from the state insurance exchange informing them of the special enrollment period.

“We jumped at the chance to sign her up,” Bruce Gravlin said.

The rest of the states rely on the federal health insurance exchange, healthcare.gov. The federal government has not changed its rules to allow those previously uninsured to sign up. As of now, they must wait until fall for the open enrollment period.

Congress has provided funding for free testing for the uninsured but not for treatment. And the federal stimulus that passed last month is dispensing $100 billion to hospitals, which can go toward COVID-19 treatment for the uninsured.

Florida has not expanded Medicaid and uses healthcare.gov for Obamacare health plans.

“It’s absolutely terrifying for those without health insurance,” said Louisa McQueeney, program director for Florida Voices for Health, which advocates for affordable health care for all Floridians and has long promoted Medicaid expansion in the state. Republican lawmakers and Republican governors in Florida have brushed aside that step and the present crisis doesn’t appear to have moved them.

That is a shortsighted response during a mass infectious disease outbreak, health policy analysts say. “The fear now is that people who need it won’t come into care,” Volk said.

The COVID crisis did not create the patchwork of different health insurance policies among states and the federal government, but the pandemic has made the differences more stark, said Jesse Cross-Call, a senior health policy analyst with the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a left-leaning research and policy institute in Washington, D.C.

“When access to health care is more important than ever,” he said, “this situation points out what a difference it makes where you live.”

Congressional action on COVID-19 imposes some new limits on state Medicaid agencies during the crisis. The rules aim to ensure that states don’t cut back coverage or narrow eligibility, and give them additional options such as streamlining enrollment procedures if they choose to exercise them.

The Families First Act, passed in March in response to COVID-19, makes more federal Medicaid money available to the states and prevents states that receive the money from dropping anyone from the rolls during the emergency, even enrollees whose incomes go up or who fail to provide required paperwork.

Under the law, states may not receive the federal coronavirus money if they eliminate any class of beneficiaries. For example, if a state had extended Medicaid to homeless people, it couldn’t stop covering that group of people now.

States also may not receive the money if they introduce or increase Medicaid premiums. The few states that do charge premiums and copays can also eliminate them, as at least five of them are doing.

“Copays and premiums are not money makers,” said Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors. “It was really a philosophic move some states took to reinforce the notion that health care isn’t free. In a pandemic, that notion has to take a back seat so we don’t put any barriers in front of people being covered.”

Enrollment Anticipation

In the coming months, states are anticipating a surge in Medicaid enrollment and a flood of people seeking coverage through the insurance marketplaces.

The Obamacare marketplace numbers in Colorado already have seen a rapid rise, said Luke Clarke, a spokesman for Connect for Health Colorado, the state-based exchange there.

As of Tuesday night, enrollment in Obamacare had climbed by 8,009 since March 20, compared with 878 for the same period a year earlier. “That’s comparable to the big days in the traditional enrollment periods,” he said.

Arizona reported April 1 Medicaid rolls 43,000 higher than the year before, with most of that increase coming in the previous month.

In Maryland, Medicaid enrollment was 4% higher this past March compared with March 2019, and enrollment in Obamacare health plans was up by 5,100 over the same period, said Andrew Ratner, chief of staff at the Maryland Health Benefit Exchange.

“We have begun to see a coronavirus bump,” he said. “It will become more pronounced in the coming months since job losses didn’t begin until nearly midway in March and many people may have employer coverage extended for several weeks or months.”

In Connecticut, enrollment in Obamacare policies increased by about 3,900 since March 20. Enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP jumped by 18,000.

Medicaid is jointly financed by the state and federal governments, with the state contributing between 50% and 78% depending on a state’s per capita income. In its COVID-19 legislation, Congress increased the federal contribution by 6.2 percentage points.

But even with the additional federal dollars, governors say states will have a hard time coming up with the revenue to cover their share of the costs of new beneficiaries. The National Governors Association is asking Congress for more Medicaid money.

Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.