By Mike Armour, Western Sydney University; Jane Chalmers, Western Sydney University, and Melissa Parker, ACT Health

Nine in ten young women experience the cramping or stabbing of period pain just before their monthly bleed or as it starts.

Period pain (also called dysmenorrhoea) can be divided into two main types – primary or secondary dysmenorrhoea – depending on whether there’s an underlying problem.

Primary dysmenorrhoea occurs in women with normal pelvic anatomy. It’s due, at least in part, to changes in hormone-like compounds called prostaglandins. Too much of a prostaglandin called PGF2a causes the uterus to contract.

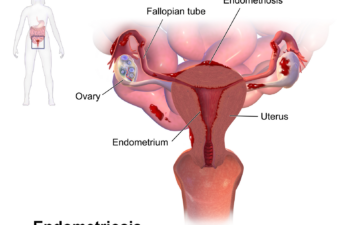

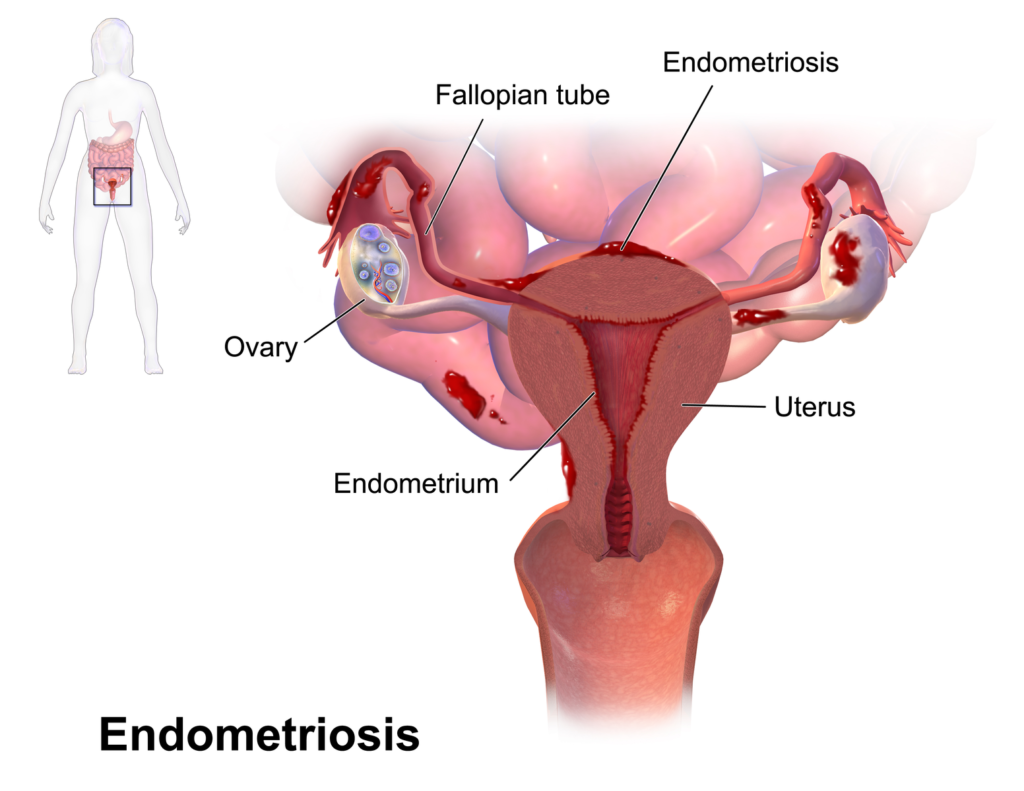

Secondary dysmenorrhoea is period pain that is caused by underlying pelvic problem and the most common cause is endometriosis. Endometriosis occurs when tissue similar to the lining of the uterus (the endometrium) is found outside the uterus.

Period pain is common

Endometriosis can cause a number of severe symptoms, including period pain.

But painful periods alone, even if they are bad, aren’t a surefire indicator of endometriosis.

Of the 90% of young women in Australia who experience period pain, most will have symptoms suggestive of primary, rather than secondary, dysmenorrhoea.

The exact number of women with endometriosis is still unclear but estimates suggest between 5% and 10% of reproductive-aged women have endometriosis.

So, most young women with period pain are likely to have primary dysmenorrhoea rather than endometriosis.

When does it start?

Primary dysmenorrhoea usually starts within the first three years after the first period and tends to get less severe with age.

Some women with endometriosis have pain that starts with or soon after their first period, while some women with endoemtriosis have relatively “normal” periods and their pain gets much worse after 18.

Jeffrey Lin

Period pain

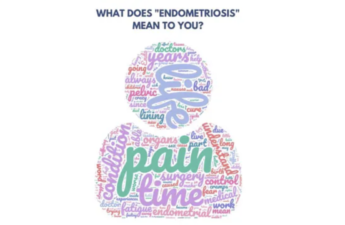

Women tend to describe period pain from primary dysmenorrhoea as “cramping”, but it’s different for each woman. It can also feel stabbing or sharp; women with endometriosis use similar descriptions.

Pain from primary dysmenorrhoea can range from very mild to quite severe, while moderate to severe period pain is one of the most common symptoms women with endometriosis experience, regardless of their age.

Pain outside the period

One type of pain that isn’t common in primary dysmenorrhoea is “non-cyclical” or “acyclical” pelvic pain: pain below your belly button that occurs on a regular basis when you are not having your period. It might not be every day but commonly at least a couple of times per week.

Non-cyclical pelvic pain is very common in women with endometriosis, especially among young women but isn’t commonly associated with primary dysmenorrhoea.

Bowel and bladder pain or dysfunction

Bowel and bladder pain are common symptoms of endometriosis, and symptoms can vary greatly. Some women report bowel and/or bladder pain during their period, while others experience the pain outside of their period.

More than half of women with endometriosis urinate more often and many experience pain with urination on a regular basis.

Bowel changes can mimic symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, including more or less frequent bowel movements, and harder stools or diarrhoea.

Painful sex

Women with endometriosis are nine times more likely to experience painful sex (dyspareunia) than women without endometriosis. This is usually described as “deep dyspareunia” – pain occurring high in the vagina and usually associated with thrusting.

Many women also experience burning pain after intercourse, which can last for hours or days.

Managing primary dysmenorrhoea

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (such as ibuprofen) and the oral contraceptive pill are common treatments for primary dysmenorrhea and can be very effective when taken correctly.

There is also evidence heat and other physical activities such as yoga and stretching can reduce primary dysmenorrhoea symptoms.

So do I have endometriosis?

If your period pain is mild and occurs just prior to or during your period, and it doesn’t cause you to miss work or school, then your risk of endometriosis is low. But it’s important to note not all women with endometriosis will have symptoms. In asymptomatic women, endometriosis is often only diagnosed when they encounter fertility issues.

Women with endometriosis are more likely to exhibit the symptoms detailed above, but having one or all of these symptoms is not definitive for a diagnosis of endometriosis. The formal diagnosis of endometriosis is made using laparoscopy, where a small camera is inserted into the pelvic/abdominal cavity looking for endometriosis lesions.

There are other causes for some or all of these symptoms, including adenomyosis (where cells grow in the muscle of the uterus), uterine fibroids (non-cancerous growths in the wall of the uterus), vulvodynia (vulvar pain which doesn’t have a clear cause) and irritable bowel syndrome (which affects the functioning of the bowel).

When do I need to speak to my doctor?

If you have any of the following, it’s worth getting in touch with your doctor:

- regular non-cyclical pelvic pain, pain during sex, or pain related to your bladder or bowel motions

- period pain that doesn’t respond well to ibuprofen or the pill, and you’re still in enough pain to prevent you from going to work or school

- sudden onset of severe period pain, or a significant worsening, after the age of 18

- changes in your cycle, such as bleeding more than normal or at unusual times

- symptoms that interfere with your ability to do normal things like go to school or work

- pain or other symptoms, plus a mum or sister who has endometriosis (research suggests you are at higher risk of having endometriosis yourself).

Or, if you just feel like there is something wrong, go and speak to your GP or gynaecologist. They will be able to discuss options for further investigations and treatment.![]()

Mike Armour, Post-doctoral research fellow, Western Sydney University; Jane Chalmers, Lecturer in Physiotherapy, Western Sydney University, and Melissa Parker, Clinician and Researcher, Canberra Endometriosis Centre, ACT Health

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.