Cheryl Walter, University of Hull

A recent spate of severe liver inflammation (hepatitis) has been reported in previously healthy children. As of April 21, there have been 169 confirmed cases of “acute hepatitis of unknown origin” in children in 12 countries, with the vast majority of cases (114) occurring in the UK. Many of the children are under ten years old.

What has been very concerning for health professionals reporting on these cases is the severity of the disease in these young, otherwise healthy children. Seventeen have needed a liver transplant, and one child has died of liver failure.

The number of transplants is far higher than what has been typically seen over similar time periods in previous years. While acute hepatitis is not unheard of in children, these latest figures are unprecedented, and so far, only partly explained.

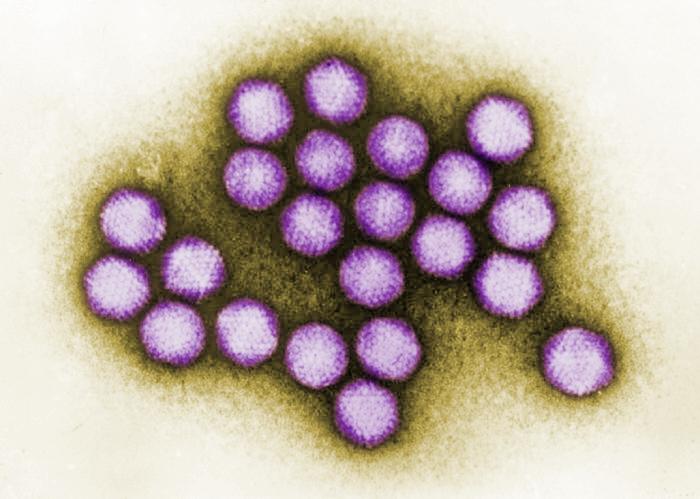

One suspect is infection by an adenovirus. According to the UK Health Security Agency, adenovirus was the most common pathogen found in 40 of 53 confirmed cases tested in the UK. The agency said that “investigations increasingly suggest that the rise in severe cases of hepatitis may be linked to adenovirus infection but other causes are still being actively investigated”.

Adenoviruses

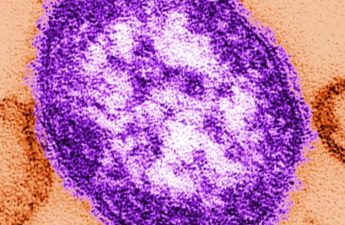

Adenoviruses are a large group of viruses that can infect a wide range of animals as well as humans. They got their name from the tissue they were initially isolated from: the adenoids (tonsils).

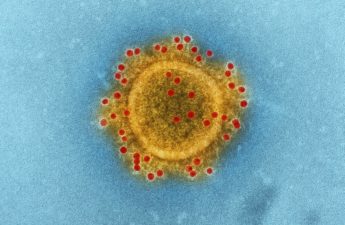

Adenoviruses have at least seven distinct species, and within those species, there are genetic variants just like we see with coronaviruses and other viruses. In this case, instead of variants, they are referred to as adenovirus subtypes.

Adenoviruses cause mild illness in humans, most of the time. Some species cause respiratory-like illnesses, such as croup in young children and babies. Others cause conjunctivitis, and a third group causes gastroenteritis.

The subtype associated with the current acute hepatitis outbreak in children is called adenovirus subtype 41, with the virus detected in at least 74 cases so far. Subtype 41 belongs to the adenovirus clustering that is typically associated with mild-to-moderate gastroenteritis; essentially a stomach bug with symptoms of diarrhoea, vomiting and abdominal pain.

In most children and adults with a healthy immune system, adenoviruses pose a mere annoyance, resulting in an illness expected to pass in a week or two. Viral hepatitis from infection by adenoviruses has only been reported previously as a rare complication.

Because of the number of cases and the severity of the disease in children, scientists are urgently investigating the cause of the outbreak. Early in the outbreak, epidemiologists sought to identify contact links with these cases and, of course, to identify what the cause of the viral hepatitis was. It quickly became apparent that this wasn’t just a small, isolated cluster of cases.

Data from the Scottish National Health Service) revealed that none of these children lived in a discernible geographical pattern (such as near an open water source), that the average (median) age at hospital admission was four years old, and no other obvious traits, such as ethnicity or sex, were found to be associated with the disease. Similar findings were reported by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Because some of the COVID vaccines used adenoviruses, some people on social media wondered if the vaccines were the cause of the outbreak. However, none of the cases reported in the UK had received a COVID vaccine and the COVID vaccines that do use adenoviruses use an unrelated virus that cannot multiply.

Questions that need to be answered

Researchers still need to find a direct causative link between adenovirus 41 and these cases of hepatitis. Are there any other complicating factors that contribute towards serious disease, such as co-infection with another virus, such as coronavirus?

Sampling the population (both adults and children) to get an idea of how prevalent adenovirus 41 is in these reporting areas versus other areas of low to no incidence would help firm up the link. Scientists also need to discover the genetic makeup of the virus. Has it changed significantly from the reference information we have on it?

It will be crucial to understand the immune response in these cases versus other mild adenovirus infections. And research into prevention (vaccination) and treatment options, such as antiviral medication, also needs to commence.

Hopefully, we will have some answers – and treatments – soon. In the meantime, parents should be vigilant for hepatitis symptoms in their children, including yellowing of the eyes and skin (jaundice), dark urine, pale poo, itchy skin, feeling tired and tummy pain.

Cheryl Walter, Lecturer in Biomedical Science, University of Hull

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Read the original article.