These Pills Could Be Next U.S. Drug Epidemic, Public Health Officials Say

By Christine Vestal, Stateline

The growing use of anti-anxiety pills reminds some doctors of the early days of the opioid crisis.

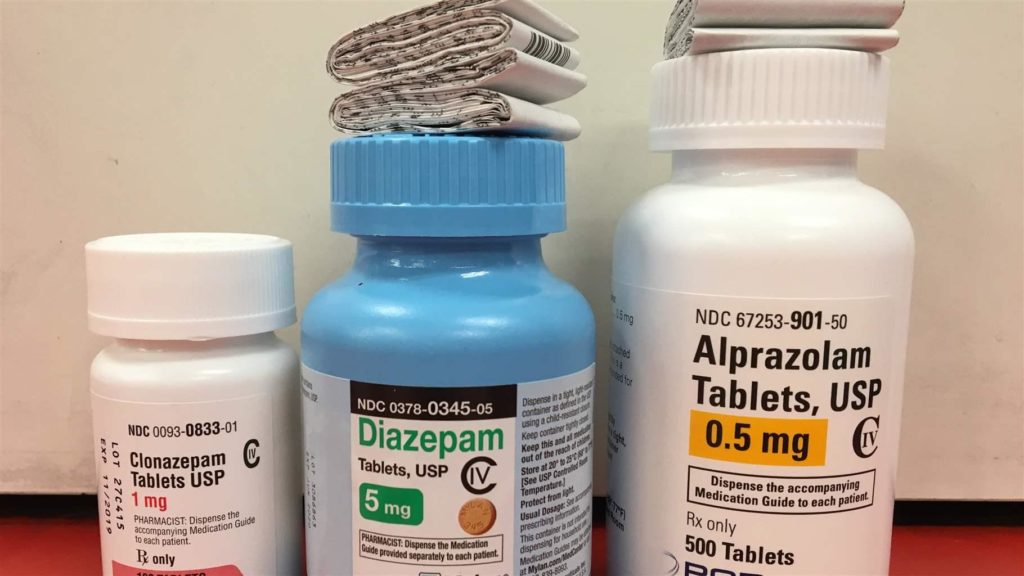

Considered relatively safe and non-addictive by the general public and many doctors, Xanax, Valium, Ativan and Klonopin have been prescribed to millions of Americans for decades to calm jittery nerves and promote a good night’s sleep.

But the number of people taking the sedatives and the average length of time they’re taking them have shot up since the 1990s, when doctors also started liberally prescribing opioid painkillers.

As a result, some state and federal officials are now warning that excessive prescribing of a class of drugs known as benzodiazepines or “benzos” is putting more people at risk of dependence on the pills and is exacerbating the fatal overdose toll of painkillers and heroin. Some local governments are beginning to restrict benzo prescriptions.

When taken in combination with painkillers or illicit narcotics, benzodiazepines can increase the likelihood of a fatal overdose as much as tenfold, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. On their own, the medications can cause debilitating withdrawal symptoms that last for months or years.

Public health officials also warn that people who abruptly stop taking benzodiazepines risk seizures or even death.

With heightened public awareness of the nation’s opioid epidemic, some state and local officials are insisting that these anti-anxiety medications start sharing some of the scrutiny.

“We have this whole infrastructure set up now to prevent overprescribing of opioids and address the need for addiction treatment,” said Dr. Anna Lembke, a researcher and addiction specialist at Stanford University. “We need to start making benzos part of that.”

“What we’re seeing is just like what happened with opioids in the 1990s,” she said. “It really does begin with overprescribing. Liberal therapeutic use of drugs in a medical setting tends to normalize their use. People start to think they’re safe and, because they make them feel good, it doesn’t matter where they get them or how many they use.”

“What we’re seeing is just like what happened with opioids in the 1990s.”

— Dr. Anna Lembke, researcher and addiction specialist Stanford University

The number of adults filling a benzodiazepine prescription increased by two-thirds between 1996 and 2013, from 8 million to nearly 14 million, according to a review of market data by Lembke and others in the New England Journal of Medicine. Despite the known dangers of co-prescribing painkillers and anti-anxiety medications, the rate of combined prescriptions nearly doubled between 2001 and 2013.

Since then, prescriptions for benzodiazepines may have leveled off or declined slightly, according to recent data from a market research firm that tracks prescription drug sales, the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. At the same time, opioid prescribing has dropped by more than a fifth.

Still, Lembke said, the level of prescribing is much higher than it was in the mid-1990s and benzo dependence appears to be rising based on her own clinical observations.

First marketed in the early 1960s, benzodiazepines have been cyclically abused throughout their history. What’s notable now, Lembke said, is that overuse of benzos is coinciding with overuse of opioids.

But a newly formed group of researchers and pharmacologists, the International Task Force on Benzodiazepines, wrote in an editorial that recent negative publicity has made it difficult for many doctors around the world to prescribe medications they consider essential.

Some scientific articles “achieved a common goal that negative propaganda frequently reaches: they aroused suspicion of benzodiazepines and suggested difficulties in using them, while overlooking their benefits,” the pharmacologists said. (Three of the 17 co-authors reported having consulted for or received support from drug companies.)

Psychiatrists, including Lembke, agree that relatively inexpensive benzodiazepines can be effective at relieving acute cases of anxiety and sleeplessness.

Physicians agree that benzos should not be used long term to solve psychiatric problems. Research indicates that use of the drugs for more than a few weeks can cause tolerance, including withdrawal symptoms between doses, and physical and psychological dependence.

“Doctors need to be informed that the medications should be prescribed for no more than two to four weeks. They were always meant to be short term.”

— Dr. Christy Huff, co-director Benzodiazepine Information Coalition, Utah

To raise awareness of benzodiazepines’ dangers, Hawaii, Pennsylvania and New York City have issued prescribing guidelines that limit the duration of Xanax, Valium and other benzo prescriptions, similar to many state guidelines for opioids.

In addition, the Massachusetts Legislature this month passed a wide-ranging opioid bill that included benzodiazepines as a class of restricted drugs.

Nationwide, most states require doctors and pharmacists to track opioid prescribing through online databases that monitor patients who receive them and doctors who prescribe them. Benzodiazepines are not included in half of the states, according to an analysis of state laws by The Pew Charitable Trusts, which also supports Stateline.

Mounting Dangers

As prescriptions for benzodiazepines have grown since the late 1990s, so have deaths, according to a study at Montefiore Medical Center in New York. The National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines quadrupledfrom 2002 to 2015.

New highly potent forms of benzodiazepines that are illicitly traded are also causing overdose deaths, addiction doctors say. Adding to the dangers, the Drug Enforcement Administration has reported that the deadly synthetic drug fentanyl has been found in counterfeit forms of Xanax.

Xanax and Valium were involved in more than 30 percent of opioid overdose deaths between 2010 and 2014, far more than cocaine and methamphetamines, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In some parts of the country, the prevalence of Xanax in drug overdose autopsy reports was even higher.

Xanax for the past several years has been found in more overdose autopsies in Kentucky than any specific opioid, according to Dr. Kelly Clark, president of the American Society of Addiction Medicine and an addiction doctor who lives in the state. “In fact, community mental health centers in Louisville stopped prescribing Xanax because it is such a common drug of abuse and so dangerous in combination with alcohol and opioids,” she said in an interview with Stateline.

Better Information

Researchers and patient advocates argue more needs to be done to educate medical students and inform doctors and patients about the drugs’ dangers.

Dr. Christy Huff, who is in recovery from dependence on Xanax, co-directs the Utah-based Benzodiazepine Information Coalition. The nonprofit advocates for stronger warnings for patients who take Xanax and other benzos, as well as better education for prescribing physicians.

“Our population of patients is experiencing extremely difficult withdrawals, and they have neurological injuries because of unsafe prescribing,” Huff said. “Doctors need to be informed that the medications should be prescribed for no more than two to four weeks. They were always meant to be short term.”

In 2016, the Food and Drug Administration issued a warning about the dangers of combining opioids and benzodiazepines. That prompted many doctors to force patients to choose one drug over the other without warning them about the potential symptoms of withdrawal such as seizures or even death, Huff said.

“Patients who are on the medications should be given the choice of how and when they are tapered off,” she said. “Too many doctors are taking people off their prescriptions too rapidly.”

The benzo task force wrote in its editorial that it was developing research that it hoped would support preserving the drugs as a valuable part of the medical arsenal.